Afghanistan: a failure, now what?

Dedicated to the memory of the NATO soldiers who lost their lives in Afghanistan, as well as the civilians killed since 2001.

This week we have seen the shameful (for the West) end of the war in Afghanistan, the conflict that has most marked this century, not only for its duration (almost 20 years), but also for its impact on daily life, as air travel is now remembered more for the security checks than for the flight itself.

All of us (not only those of us who work in geopolitical analysis, armed forces and journalists) have been surprised by the speed with which the Taliban took over the country. This is not to say that the fall of the Kabul government was not foreseen - it was known in advance that, without international assistance, Ghani's cabinet would not hold. However, the most pessimistic forecasts expected the government to fall in a few weeks, not just six days1. To put this in perspective, the South Vietnamese government took two years to fall after the signing of the Paris Accords in 1973. In Afghanistan, the fall has actually taken a year and a half since the agreement reached between the Trump Administration and the Taliban in February 2020.

Will there be another refugee crisis because of this? What moves will Russia, China and Iran, all three bordering Afghanistan and with interests in the area2, make? And finally, how is it possible that the US, the vaunted champion of its form of democracy, has left Afghanistan in such an unseemly manner and what message does it send to its allies regarding its security guarantee?

The possibility of a second wave of refugees, equal to or larger than that of 2015-16, worries Brussels, which is recovering from COVID-19 and trying to get Eastern countries, especially Poland and Hungary, to respect the rule of law and gender diversity, an issue that has created quite a few rifts. Between Afghanistan and the EU there are two borders (Iran and Turkey). To date, both countries do not have good relations with Brussels, the former because of sanctions over human rights violations and the EU's inability to resurrect the nuclear deal, while in the case of the latter, mutual unease is well known over issues such as condemnation of repression following the 2016 Turkish coup, energy exploration in the eastern Mediterranean and Turkey's feeling that it was betrayed by the EU with the 2016 agreement to stem the flow of refugees, as Ankara feels that Brussels did not keep its side of the bargain3.

Add to this that Turkey has a stake in Afghanistan's future. A little known fact is that Kabul's international airport has been under Turkish control since the beginning of NATO missions (ISAF and Resolute Support), giving the country a position of relevance on the ground as one of the most modern facilities in the country.

Moreover, Turkey - unlike the other countries present in the country - is Muslim-majority, which gives it an advantage in influencing the country's future. It is also an ally of Pakistan, whose support for the Taliban is an open secret. The wily pasha Erdogan would like to maintain good relations with the Taliban, using his rapport with Islamabad to agree on how to police Taliban excesses and agree to create a hypothetical common front if Brussels were to criticise Turkish recognition of the Taliban government, threatening potential waves of refugees, something Brussels and Turkey do not want. As a result, Ankara is well positioned to cause the EU another refugee headache, as it did in 2016.

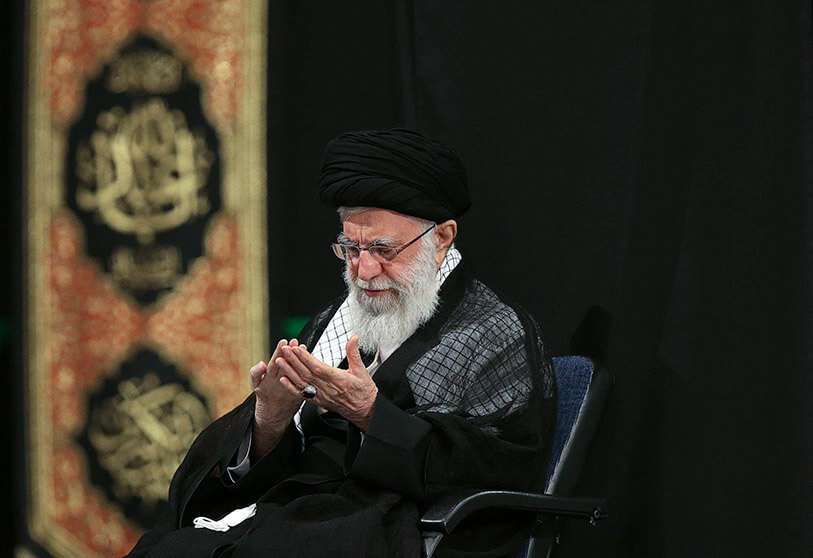

As for the moves by Tehran, Moscow and Beijing, it is best to look at each individually. At first glance, Iran is the worst offender, as the Taliban are Sunnis, enemies of the Shia, the religion of the Iranian theocracy and of part of the Afghan population. It is foreseeable that the Taliban could launch attacks on Iranian soil, taking advantage not only of the border but also of the fact that Iran hosts a large number of Afghan refugees on its territory, thus facilitating their infiltration to commit their misdeeds. However, there is as yet no record of Taliban retaliation against the Hazara minority - which is Shia - and the Taliban have pledged to respect religious diversity. If this were to happen (let's not forget that this is an assumption), Iran could open trade relations with the Taliban, opening up a market for its economy - weakened by Western sanctions.

Beijing has already reached out to the Taliban, taking advantage of Trump's gift of legitimising them as international actors. For China the challenges are a reflection of the geopolitical and security realities of this century: Afghanistan is a key country in China's dream of a new Silk Road, not only for the passage of goods, but also to establish its hegemony in the country, through control of roads, river ports and gas pipelines4, and knowing Beijing, it will strike a deal to control them for a long period of time. On the security front, China is busy repressing the Muslim Uighur minority in Xinjiang, which borders Afghanistan. Kabul could become a hotbed of radicalisation for young people from this group, something China will want to avoid if it is not to suffer the scourge of jihadist terrorism. It is therefore better to ally with them in order to avoid long-term misfortune.

Finally, Moscow has already played its realistic card, with its ambassador meeting with the Taliban. Given that they got stuck in the country for eight years, exiting disastrously (but not chaotically), Moscow's move is understood as a way to avoid getting involved again if the situation worsens. This is because the Central Asian republics, which are Muslim and have ethnic affiliations with Afghanistan, are Moscow's allies and will most likely ask Russia to intervene, taking advantage of the fact that it has a military presence in these republics. Putin will not want to relive the Afghan nightmare, hence the ambassador's meeting. There is also the economic card to consider, as investment opportunities are opening up in Afghanistan, something that Russia, which, like Iran, is under the yoke of international sanctions, will not squander.

Finally, mention should be made of what the embarrassing American withdrawal means for its allies, especially in terms of the perception of a hypothetical end of the American security shield in the world.

Joe Biden's speech on Monday sent a clear message: the era of the United States as the world's gendarme and mentor of global democracy (nation building) is over. Of course, this message leaves open the question of what will happen to America's military presence in the world. If, as Biden said, the US will only intervene if its security is directly threatened, what is the point of US troops stationed in Europe, Washington's ally? Seoul and Tokyo should also be concerned, for while it is true that both border China, the new US rival for world hegemony, both Beijing and North Korea have not launched terrorist actions against Washington, except for hacks that Washington has attributed to both countries, although it is difficult to clarify who is really behind them. It should come as no surprise that voices in America will soon be heard calling for a return to the isolationism of the inter-war period or a reduction of American intervention to the basics, arguing that Europe, South Korea and Japan are economically strong enough to manage their security on their own. Although this has been going on for a long time (both Obama and Trump have already shown signs of a reorientation of American foreign policy against China that is less costly in lives and money), it is true that Biden's speech was the definitive confirmation that Trump's foreign policy postulates on the matter - which seemed exaggerated to us Europeans - were indeed the majority sentiment in the United States, since nobody is going to question that Biden - vice president with Obama - is crazy, nor that his advanced age is playing tricks on him.

In conclusion, the rapid collapse of the Kabul government this month has opened fears in Brussels of a second wave of refugees equal to or worse than the first in 2015-16. Turkey, with interests in the country, will be the one to decide whether this happens or not, which will depend on whether the EU willingly accepts Ankara's recognition of the Taliban government. A negative reaction from Europe could trigger the second wave, especially as Turkey has good relations with Pakistan, an ally of the Taliban.

Iran, China and Russia also have interests in the country. While Iranian Islam is anathema to that of the Taliban, if the Taliban respect the Shi'a, it could open up the possibility of trade relations for Tehran, an opportunity that would oxygenate Iran's sanctioned economy. China wants Kabul as part of its New Silk Road dream, the expansion of its influence through trade. The country's roads and pipelines, not to mention its position as a gateway between Asia and Europe, are of interest to Beijing, which will be sure to control them to its advantage. Moreover, China would like to prevent Afghanistan from becoming a point of radicalisation for Xinjiang's Uighurs. Finally, Russia has already adapted to reality, with its ambassador meeting with the Taliban. Moscow, already familiar with the Afghan hornet's nest, will avoid getting involved if the situation deteriorates. Moreover, good relations with the Taliban would open up many business opportunities, something that Russia's strained economy would welcome.

Finally, Biden's announcement that the US will no longer restore democracy around the world opens the door to debate over the usefulness of the US protective shield in Europe, Japan and South Korea. With China as the new enemy to beat, and with these three areas economically strong and allied, there may soon be voices in Washington calling for an end to the US military presence there, arguing that it costs too much money and that the countries described above are capable of managing their security on their own. This speech, which seemed to us to be from the Trump era, said by Biden taught us that the US is tired of venturing into conflicts in distant countries that cost a lot of money and the lives of its citizens. The mindset has changed in Washington, but it seems that in Europe this shift has not yet taken hold, whether we like it or not.

References:

1 - See US fears Afghanistan could fall to Taliban within weeks | World | The Times

2 - While Russia does not have a direct border with Afghanistan, the Central Asian Republics - Moscow's allies - do.

3 - Simplification of visa procedures and financial assistance to facilitate the reception of refugees on its territory.

4 - See: Afghanistan - The World Factbook (cia.gov)