Moderniser or plunderer, Napoleon left his mark on the whole of Europe

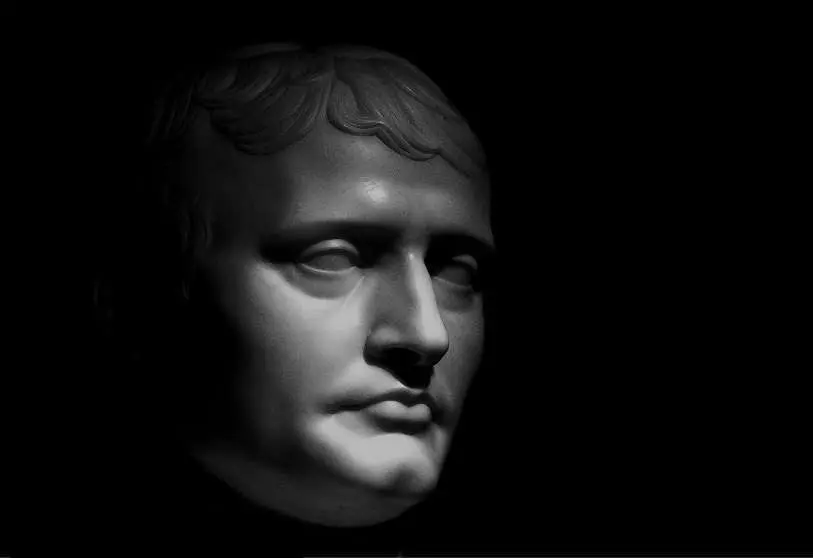

It will be 200 years on 5 May since the death of Napoleon Bonaparte, the first consul and later emperor of France. It is not an imperial celebration, because he remains the most controversial global figure in Europe: unquestionable statesman and moderniser of France for some; insatiable conqueror, guilty of having sown Europe with blood and fire, for others. One of the great ambitions of Europeanism is still a long way off: to achieve a single core textbook on the history of the continent. Thus, the French emperor, apart from Hitler and Stalin of course, continues to embody more than any other figure the great emotional differences that still exist in Europe's internal borders.

Waterloo, on the plains of Flanders, went down in common European history as the scene of the final defeat of the man who, instead of achieving the unification of Europe under his aegis, would bring about a new division of territory and influence. While the Congress of Vienna (1815) agreed the new borders, the man responsible for that first great pan-European war was banished to the remote island of St Helena in the South Atlantic, where he died on 5 May 1821.

A flood of new books is being published in France to mark the commemoration. Debates and discussions abound in all kinds of forums about the man who, in 1799, put an end to the chaos that had resulted from the Revolution of 1789, the regime of terror and the orgy of bloodshed that had followed the overthrow of the absolutist Monarchy.

As seems to be a universal tendency, there is a marked tendency to judge Napoleon out of context of his time and to conflate him with the political antagonisms of today. As a result, he is accused of being a slaveholder and of having put an end to the revolutionary Republic, seen as an idyllic system and an idyllic environment. There are voices, few and far between, that propose the removal of his ashes from the impressive mausoleum of the Invalides, where they were placed after King Louis-Philippe succeeded in transferring the emperor's remains to Paris in 1840. Few are also those who, in the opposite direction, propose a re-reading that uncritically extols his figure. Most, fortunately, are inclined to narrate the events in the context of his time, when England had already become master of the seas, Spain was struggling to keep the pillars of its immense but declining empire in place, Prussia was still dreaming of unifying a powerful Germany, and Russia was extending its accelerated geographical expansion as far as the Caucasus.

Without regret for the shadows, but also without denying the lights of his legacy, the commemoration of this bicentenary aims to avoid placing the blame for the immense massacres and exactions caused by the imperial troops. Although it may be hard to recognise, history has written its greatest achievements and innovations spurred on by its wars, without hiding the personal and collective tragedies that were their price.

We Spaniards have just commemorated the 213th anniversary of the uprising of the people of Madrid, first, and then of the whole of Spain, against the kidnapping of the royal family and the occupation and sacking of the country by French troops. It was our own War of Independence, the summary of which was devastating: it wiped out the country's demography, plundered its cultural heritage, destroyed the leading sectors of Spanish industry and, above all, provoked the movements that would lead to the independence of Spanish America. In return, Napoleon I left behind 170,000 dead in Spain and the conviction that the catastrophic end of his empire had its roots in his errors of approach and strategy in the country where he had enthroned his brother Joseph I.

There are many who believe that, faced with a common external villain like Napoleon, the Spanish people formed their first sense of national identity. Moreover, the liberal flame lit by the Constitution of Cadiz in 1812 would take hold both in European Spain, despite its crushing by the felon Ferdinand VII, and in American Spain, which would transfer the innovative principles of "la Pepa" to its successive declarations of independence.

Two hundred years later, most researchers agree that the reforms undertaken by Napoleon since his enthronement in 1799 have left their mark on the whole of Europe, which has literally copied or adapted many of his innovations. These include his Civil and Criminal Codes; the creation of the Bank of France; the future Paris Stock Exchange; 22 Chambers of Commerce; the Court of Cassation; the baccalaureate and the grandes écoles, and even new ways of organising city life, such as compulsory rubbish collection and the ordered numbering of houses built along the sides of streets. He was also responsible for the creation of the Legion of Honour, a reward for the merits and services to the country of deserving citizens, whether civilian or military.

Napoleon Bonaparte is, therefore, history, an impressive site for researchers and professional historians. His figure, for better or worse, cannot be eradicated from that history. Unless, of course, today's politicians insist on using him as a weapon for their present-day disputes.