Taking advantage of Erdogan's weakness

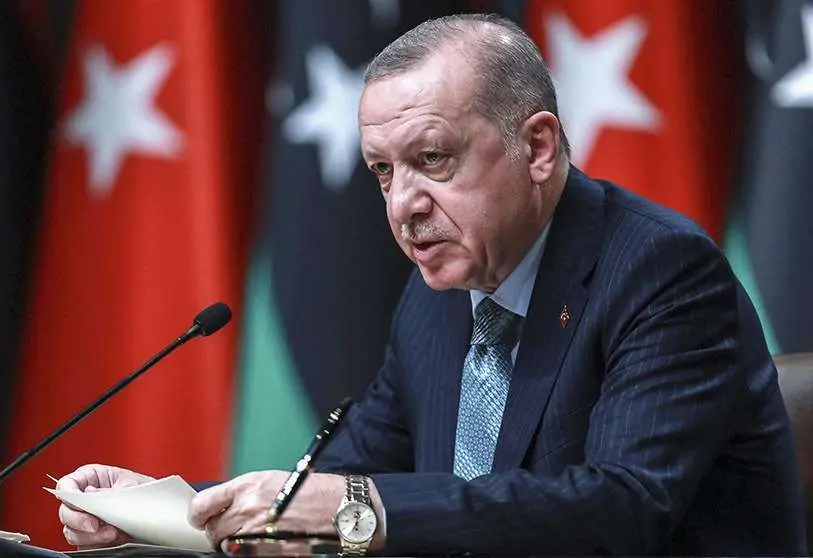

President Joe Biden would probably not have taken the decisive step of recognising the "Armenian genocide" if Turkish economy was not in a weakened state. His predecessors, some with the clear intention of doing so, backed off. Ronald Reagan was the first in 1981 to call the massacres of Armenians by the Ottoman Empire between 1915 and 1923 genocide, according to the definition that the United Nations incorporated into international law in 1948: "The intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group". Barack Obama, who twice vowed to make good on his promise to do so, would also backtrack. And, of course, Donald Trump did not even contemplate such a possibility as soon as he held his first meeting with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who put on the table the "casus belli" that such a hypothetical action would entail for relations between Ankara and Washington.

In all cases, the US Secretary of State, Pentagon and security agencies advised the relevant White House occupant against describing the mass ethnic cleansing of Armenians with the same word as Nazi Germany's mass liquidation of Jews. Geopolitics rules and Ankara was a NATO mainstay in southeastern Europe, so there was no question of poking around its sensitivities.

Since the very founding of the Republic of Turkey by Kemal Atatürk, successive governments have invested large sums of money in preventing any recognition of the Armenian genocide. But the pressure has increased exponentially with Erdogan in power, especially in the wake of strained relations with both the United States and the European Union. It is precisely the Turkish president's rudeness, undisguised authoritarianism and threats to change his loyalties that have led to growing distrust of his once staunch ally in both Washington and Brussels.

Its intervention in the Syrian war, which has tended more to fight a war of extermination against the Kurds than to solve the war that has reduced a large part of the country to ashes in ten years; the purchase of sophisticated Russian weapons while it is a member of NATO and the latter has a hard time with Vladimir Putin; the design of its own policy in the Libyan conflict, almost outside of its allies; its unconditional support for Azerbaijan in its latest war with Armenia over the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh; but, above all, its lack of real active collaboration in the fight against Daesh, have been the causes that have led Biden's advisors to change their stance, so that they have concluded that Erdogan is going through a moment of weakness.

The US president has seized the opportunity and thus fulfilled the promise he made as a candidate to the large and influential Armenian colony in the United States, which includes such influential media names as Cher, System of a Down, Kim Kardashian and Kirk Kerkorian.

In addition to the considerable withdrawal of international investment, Erdogan is experiencing a progressive diplomatic isolation. The Turkish president, who has amended the constitution and given himself the powers of a veritable sultan, is likely to be highly graduated in his response to Washington. In addition, Erdogan will most likely try to pay for the alleged American affront with other demands that obsess him: his war against the Kurds and the extradition of his former friend and ally, the cleric Fethullah Gülen, who has taken refuge in the United States. He blames the latter directly for the coup attempt to overthrow him on 15 July 2016. It was the pretext used by Erdogan to arrest, imprison, torture, prosecute and sentence more than 100,000 people, including considerable portions of the military, judicial, journalistic and academic elites. A full-blown regime change, where his critics see in Erdogan pretensions of a return to the Ottoman Empire.