The war in Libya and its oil resources: order inside chaos?

Libya is a synonym of instability since the First Libyan Civil Way flared, and its ruler, colonel Gaddafi was hounded out in 2011. Three years later, the Second Libyan Civil War ignited, and it is still being carried out in 2020 after six years. The obstacles for peace in Libya are several, but the ones standing out are the vacuum of power after Gaddafi’s fall, the social and political importance of the Libyan tribes, the actions of Islamic terrorism, and above all, the crude oil. The black gold acts as ‘fuel’ in the war, which at the same time grants it an exclusive shielding by both contenders, who aim to control it exclusively.

The instability which torments Libya nowadays cannot be explained only by referring to the vast oil reserves the country has and the fight for them. Instead, it is necessary to look at three other factors which shape and escalate the conflict: Gaddafi’s fall and posterior complex management of the country; the Libyan tribal framework; and the insecurity in the country consequence of terrorists. Gaddafi’s deposition happened in the context of the uprisings during the so-called Arab Spring, present in Libya between February 17th and October 20th, 2011. These revolts ended with the country model, which colonel Gaddafi had created, in a very abrupt way, with hardly any adaption time at all.

After 42 years under an authoritarian regime, but which maintained order, Libya saw itself in a civil war leading to a period of chaos and uncertainty. To avoid this anarchy, the UN involved itself developing an institutional structure called the National Transition Council. This government created after the first civil war in 2011 was supposed to solve the misgovernment in Libya. Even though the Council had the support of the UN, the newly born institution failed, and it failed in its purpose, as it did not demobilize all the armed groups of ex-combatants of the First Civil War. The Council could not impose its order for the management of the country, so the violence and insurgence continued Libyan streets.

Despite this political-social context of violence and instability, in July 2012, Libya held elections to form the General National Congress (GNC). This organism inherited the previous problems of the Council and ended up being a dysfunctional body too, unable of facing the problem of the militias. In addition, the GNC, over time, radicalized its ideology towards Islamist ideas, to get the support of a part of the population and some militias1. In 2014, when the mandate of the GNC was supposed to end for new elections to be held, the institution unilaterally extended its mandate sine die. In light of this, general Halifa Haftar launched the so-called Operation Flood of Dignity to overthrow the GNC and hold new elections which would create a new organism named House of Representatives (HoR).

Finally, the elections could be celebrated in 2014 after Haftar’s intervention, with poor results for the Islamist MPs compared to the previous 2012 ones. The Islamist sector decided then not to recognise these electoral results and to remain loyal to the GNC distribution2. This way, Libya was divided in two executives claiming to be the democratically elected ones: the GNC, made up mainly by Islamists with its headquarters in Tripoli (Western Libya) and the HoR, made up by the MPs elected in the 2014 elections, with its headquarters in Tobruk (Eastern Libya). The division meant the ‘formal’ start of the Second Civil War.

In 2016, the UN in its attempt to stabilise Libya, supported the creation of the Government of National Accord (GNA), an executive which aimed to integrate in a single structure members of both “governments”, to end the conflict in a peaceful way. However, the GNA was not able to do so, being able only to include members of the old GNC, now the war on was between the HoR and the GNA.

Added to the fall of Gaddafi and subsequent misgovernment, the Libyan involution was consequence of the historical role of the tribes in the governance of the country3. In 1951, after the Italian colonization of Libya, the king Idris I granted power to the clans, so they supported him in the rule of the country. In 1969, when Gaddafi arrived at power, the tribes did not just maintain the previous power, but they even increased their importance inside the government. Gaddafi would integrate tribal leaders in his government and practice a strategy of “divide and rule”, by which he would selectively marginalise some clans whilst privileging other clans such as Warfalla, Ghaddafa or Maghariha. Besides promoting the Arab and Libyan nation, the reason for this strategy was that if the tribes united, they could depose Gaddafi, due to the power they gathered. To avoid this, Gaddafi aimed to divide the tribes and create conflict between them, so they would never unite against him and he could rule4.

The fall of Gaddafi meant the breaking down of the status quo imposed among the tribes and the end of the preestablished order. This generated great tension between the clans whilst they searched to build a new order in which each group was on top.

Finally, it is necessary to look at the presence of terrorist groups in Libya as one of the sources of current instability. The power vacuum present in Libya since 2011, with no government or institution strong enough to impose a legal order, together with the disenchantment of the population, created the perfect space for the growth of terrorist groups. The terrorist groups could in addition strengthen themselves with all the weaponry used in the First Libyan Civil War and the one obtained from the assorted arsenals of the deceased Gaddafi. Added to the appropriate internal conditions, the external events also promoted the settling of terrorists in Libya. Firstly, the so-called Operation Bharkane carried out by the French army in the Sahel in August 2014 against extremism, encouraged terrorists to move from Niger and Chad to Libya5. Secondly, the progressive eviction of Daesh from Syria and Irak, forced its members to look for another place to stablish.

Frequently, Libya is described as a single conflict; however, it is necessary to distinguish that the war is fought at three levels: international, national, and local.

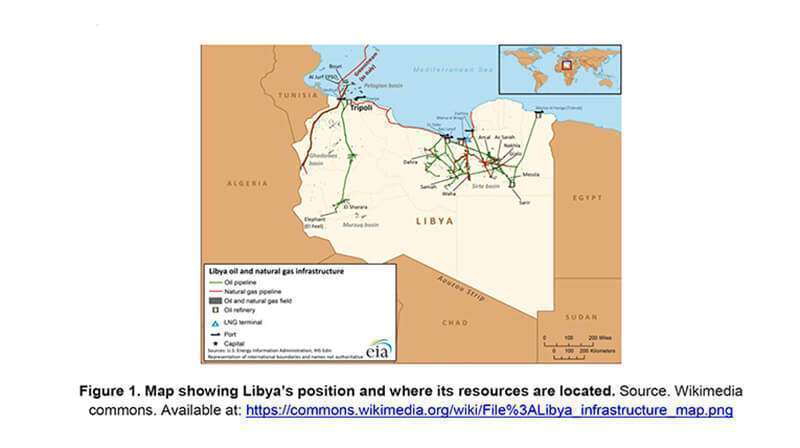

At the international level, we must consider Libya as a really enticing country for foreign powers, both for its position in the central Mediterranean and for its hydrocarbon’s reserves. Libya, as can be seen in figure 1, takes a central position in the Mediterranean, giving the country a high strategic importance and a possible global influence, as it could control the passage of boats and/or pipelines of fossil fuels crossing the Mediterranean. Therefore, an allied government in Libya would be a really valuable asset for some countries. Moreover, the fact Libya is really close to Europe makes it more important for the country not to become a failed state, a focus of terrorists, or a massive point of departure of migrants.

Secondly, Libya is really tempting for any foreign power due to the oil (the largest of Africa) and gas reserves (fourth largest in Africa) present in the Libyan land and sea. Due to its closeness with Europe, the north African country was, prior to Gaddafi’s fall, the biggest oil provider to the countries in the south of Europe. In fact, some of the most important European and global oil companies, such as BP, Total, Marathon, Repsol or OMV, are present in the country and even under the current circumstances still try to carry out operations of oil extraction and further exportation.

Among the international actors supporting Haftar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Egypt, Russia, France, and the United States stand out. The Arab countries justify their support for Haftar in their fight against political Islam and the Muslim Brotherhood political organisation. Their support for the Tobruk executive can be seen in the weaponry supplied by Egypt and UAE to Haftar6; economic capital provision by Saudi Arabia7; or the sending of troops directly, as a UN Security Council Report8 (document S/2019/914) pointed out, referring to the intervention of Sudanese and Jordan troops in favour of Haftar.

France, Russia, and the United States, hold an attitude, which although ambiguous between both parties, is more in support of Haftar than towards the GNA. France, with interests of the French oil company, Total, in the region, could be argued to support diplomatically Haftar, having blocked an EU resolution against him. In addition, there are suspicions that France, supplied Libya with military equipment9. Russia helped the East government too by blocking in April 2019 a UN Security Council Resolution against Haftar, and the Russian contractor company Wagner is present in Libya supporting Haftar10. Finally, the US has been more ambiguous regarding who they support, however its President recognised a support call to Haftar, who has double US citizenship. In April 2019, President Trump called Haftar to praise him for his fight against terrorism and the protection of the Libyan oil resources11. This phone call would suggest a greater affinity of the US administration with Haftar.

The opposite executive, the GNA, relies on the international support of the UN, the European Union, Turkey, Qatar, and Italy mainly. The UN is the GNA’s main support, not in vain it was the organism which formed the Government, and in the eyes of the United Nations Assembly, the GNA is the legitimate executive in Libya. The EU, following the example of the UN, recognised the GNA as the government of Libya, although it continuously pushes for a democratic solution for the conflict. The EU is particularly interested in a stable government in Libya which could stop the migrant pressure on Europe. In February 2020, the EU approved a European mission to make sure the weapon embargo on Libya was effective, hopping that this would contribute to de-escalate the confrontation12.

If we were to look at the States supporting the GNA, the main support comes from Turkey, as it could be seen when the Turkish parliament enacted a law in January 2020 enabling the deployment of Turkish troops in Libya if necessary13. Ankara’s interest in supporting the GNA are multiple, ranging from the rivalry it holds with the UAE (UAE as a strong Haftar’s supporter), Erdogan’s defence of political Islam, or Turkey’s attempts to strengthen its power inside the Muslim world and recover the sphere of influence of the former Ottoman Empire. This could be seen for example in the agreement signed in November 2019 between Turkey and Libya which delimited new maritime borders, which have not been recognised by the International Community. Qatar, in its role as political Islam defender and due to its tensions with the UAE, is the main GNA supporter inside the Arab world, although its help is not comparable to the one of its Arab rivals. Finally, Italy, could also be considered as an actor supporting the GNA, and it backs it internationally even if it maintains a strict neutrality. Italy’s arguments for doing so are to stop the arrival of migrants from Libyan coasts, the interests of the Italian oil company ENI in Libya, or to keep the Greenstream pipeline, which connects both countries, functioning.

The GNA, the government which the UN helped building in 2015, is in Tripoli and currently led by Fayez al Sarraj. Western Libya does not fight with an army per se, instead it funds militias to fight Haftar with the money that the GNA gets from the exportation of fuels done exclusively through the National Oil Corporation (NOC). These militias have become the real power in those areas loyal to Western Libya. Their power can be seen in big cities, including the capital, Tripoli, where these groups act as the police and they impose order, whilst the “real” governmental police has a testimonial role14.

Precisely this dependence on militias is the greatest weakness of the GNA, as it is a paid fidelity, the political or religious motivations would not be enough to retain the support of the militias to the cause, if the GNA stopped receiving money from oil exportations. In addition, the government is weak because it is blamed of being foreign, with constant calling from different Libyan domains for new elections15.

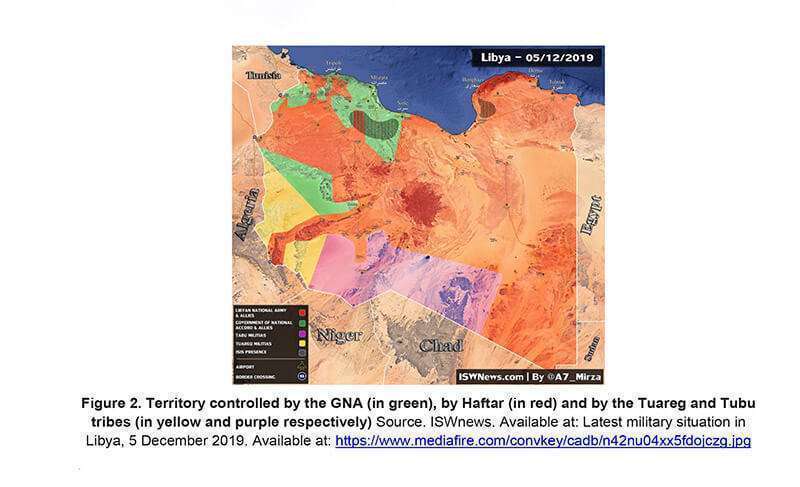

The antagonist of the GNA would be the House of Representatives, based in Tobruk, Eastern Libya. The HoR was formed according to the results of the 2014 elections but still the most visible figure of Western Libya is not a politician, but General Halifa Haftar, leader of the Libyan National Army (LNA). Since 2014, it has been Haftar who has expanded the territory loyal to the East, which by January 2020 was most of Libya (as seen in figure 2), including the surroundings of Tripoli, the Sirte oil basin (the most important in Libya) and great part of the Libyan oil camps.

Despite Haftar controlling most of the oil extraction camps, he is not able to capitalize this control of the oil facilities, as he does not receive the ‘proportional’ part of income. Haftar does not obtain all the income from oil exports of the oil camps the LNA controls, because international oil companies refuse to negotiate with any other organism aside of the NOC. As the NOC has its headquarters in Tripoli, most of the money is given to the GNA16. In Libya we can see the paradox of how the NOC divides its benefits, to finance both the GNA and Haftar, which then fight each other. Eastern Libya tried to create its own oil company and a parallel national bank to the ones based in Tripoli, in order to get all the money from the exports of Eastern Libyan oil, but these attempts failed17.

Finally, besides a civil war in the international and national level, this conflict is fought too in the local level, due to the already mentioned influence and relevance of the tribes in the Libyan panorama. Under Gaddafi there were tribes with privileges and other discriminated, but they were in equilibrium. When Gaddafi fell, this equilibrium broke, and the tribes tried to build a new system and organisation beneficious for them. To do so, tribal leaders would not hesitate to use violence and ally themselves with any of the two national actors. In fact, Al Sarraj and Haftar have instrumentalised this war between tribes to attract them to their sides.

An example of how the national sides tried to attract tribes support could be observed with Haftar’s and the HoR’s action with the Gaddafi family. In May 2018, the authorities of Eastern Libya conceded an amnesty to Gaddafi’s son, Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, hopping that this would bring the support of some tribes who had historically supported colonel Gaddafi to their side18. The truth is that nowadays, great part of the tribes that had supported Gaddafi, support Tobruk; up to what point the amnesty to Gaddafi’s son has determined the adherence of the tribes to Haftar, cannot be determined. However, in a society as the Libyan one, in which social relations are so important, such gesture was for sure important.

Another example of the tribe’s dimension can be seen in the two nomad communities present in Libya: the Tuareg and the Tubu. The Tuareg are a Berber nomadic group original from the Sahara Desert and which in Libya locates in the southwest of the country. The Tubu peoples are another nomadic group located mainly in the south of Libya from Chadian origin. In the past, both groups had clashed for ethnic-tribal reasons, in a tension which was fostered by the competition amongst them for benefits of smuggling and illegal oil trade19. It is therefore not surprising that in the First Libyan Civil War both communities battled, and considering that Gaddafi had supported the Tuareg and discriminated the Tubu, it is not surprising either that in 2011 the Tuareg fought for Gaddafi and the Tubu fought to depose him.

In the current Second Libyan Civil War, both peoples do fight too, mainly for two reasons: the first one is their eternal competition for control of the oil fields and to operate the local smuggling routes, using the excuse of the civil war to try and increase their control over both20. The second reason is a complex network of alliances and supports, in which firstly the Tuareg were neutral and the Tubu backed Haftar. When later Haftar assisted other Libyan tribes rival of the Tubu in the city of Sabha, the Tubu decided to align with the GNA. The Tuareg on their part, when they finally entered the conflict, they did it for Haftar, something which changed in February 2019, when an alliance between the Tubu and Tuareg was signed against Haftar. This precisely shows the volatility of tribes’ support, and how it varies according to the actions and rewards each side offers them21.

It is true that the confluence of actors, the chaotic overthrow of Gaddafi with no beyond vision, the influence of the tribes and the actions of terrorists, are key elements contributing to the current Libyan chaos. Nevertheless, it is also true that all these factors can be explained to a large extent in the framework of an internal quest for the control of fuels, leaving ideological, religious, or social motives aside to explain the reasons of the war. A sign of this can be seen by looking at how conflict is focused in the coast (from where oil and gas are exported), the Sirte Basin (where most of the fuel reserves are located) and the basins of Murzuq and Ghadames, and how on the opposite side, the south of the country has a lower conflict level.

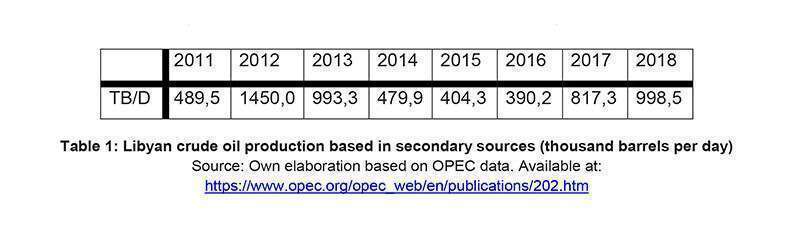

The conflict holds a direct relation with the fluctuation in oil production which the country suffers since 2011, and which heavily conditions its economy, as oil exportation mean 95% of Libya’s GDP. Table 1 shows how the situation evolved since 2011, with a low production in 2011 consequence of the First Libyan Civil War, and how after there was a recovery stage. The decrease of 2014 was consequence of the country’s division into two executives, which caused a lack of government authority, that made it possible for non-state groups to strengthen themselves and cut oil production whilst waiting to receive their share of the pay-out. In fact, in summer 2013 production already decreased with the first oil installations blockages, but this was solved later when the groups blocking the systems were hired by the GNA as ‘guardians’ of these22. Obviously, this ended up setting precedent, and blockages started to get more frequent.

In 2016, the NOC director, Mustafa Sanalla, warned the UNSMIL (UN Support Mission in Libya) responsible, Martin Kobler of the risk that yielding to blockages constituted. Sanalla did this after Kobler met with the chief of the so-called Petroleum Facilities Guard, and he pointed out that this would set up precedents and it would encourage any person in Libya which could gather a militia, to block a pipeline, oil reservoir or port with the ultimate aim of extorting23.

The reasons for these blockages are multiple: from political revindications —as in the kidnapping of Mellitah by the Amazigh (Berber tribe) in 2013—24; simple extorsions in exchange of a wage —as the Petroleum Facilities Guard in the blocking of Ras Lanuf; for the exchange of prisoners— as a militia demanded in 2019 after kidnapping Zawiya oil field25; as a way to demand the government service and security improvements, e.g. El Sharara in 201826; or as in every conflict, to debilitate the opponent, strangling it economically and to show the rest of the world who is in control.

This last reason would explain the blockages carried out by Haftar in January 2020 over the oil facilities in the area controlled by the LNA. His action showed how weak Tripoli was and how much it needed the incomes coming from the exportation of oil to finance the groups and militias that are defending the GNA. Even if Haftar declares the opposite, he holds a great interest in controlling all the production of Libyan oil, as it was shown in September 2016, when he seized the oil facilities of Es Sider and Ras Lanuf from the GNA (who had previously recovered it from Islamic terrorists)27. Haftar knows that when the GNA gets no oil benefits, the war will have an expiry date.

Overall, despite all the obstacles and disagreements, regardless of the clashes, oil commercialization is maintained, as all actors are interested in capitalizing the benefits it brings. In fact, except for the terrorist group Islamic State in Ras Lanuf in 2016, no other state or non-state group has attacked on a large-scale oil facility with the aim of destroying them. Even if oil is what is making them kill and die, they will not forget it.

Current instability in Libya is linked, to a great degree, to the struggle for the control of oil, whilst the ideological-political enmity, the Libyan tribal truss, and the effect of terrorism are just elements which complicate and instrumentalise the clash for the oil resources.

Gaddafi’s fall, possibly with no clear subsequent horizon, broke the previous status quo of oil benefits distribution, and originated the current battle between national and local actors, which use ideological enmity as pretext to legitimate the fighting. A clash in which foreign actors see the perfect opportunity to enter and achieve their objectives, adding complexity and dimension to the conflict.

A complex and broad conflict, which is fought at the local, national and international level, but in which because all belligerents need the incomes from oil, there is an iron shielding of the oil resources, as no one wants to destroy the only source of wealth of Libya nowadays and in the nearest future.

Paradoxes of conflict…or maybe not?

1 FUENTE COBO, Ignacio Libia, la guerra de todos contra todos. IEEE, Madrid, September 2014. Available at: http://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_analisis/2014/DIEEEA46-2014_Libia_Guerratodos_Contratodos_IFC._doc_final.pdf

2 Oficina de información diplomática, Ficha país Libia. Available at: http://www.exteriores.gob.es/Documents/FichasPais/LIBIA_FICHA%20PAIS.pdf

3 AL-QASEM, Abu and AL-RABO, Ali “Libyan tribes: part of the problem or the solution”. Middle East Monitor, London, August 2018. Available at: https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20180808-libyan-tribes-part-of-the-problem-or-a-solution/

4 AL-SHADEEDI, Al-Hamzeh and EZZEDDINE Nancy “Libyan tribes in the shadows of war and peace” Clingendael, The Hague, February 2019. Available at: https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/2019-02/PB_Tribalism.pdf

5 DENOEUX, Guilain “Violent extremism and insurgency in Libya” USAID, Washington DC, July 2013. Available at: https://msi-inc.com/sites/default/files/additional-resources/2018-12/Violent%20Extremism%20and%20Insurgency%20-%20Libya.pdf

6 ASSAD, Abdulkader “Revealed UAE-Egyptian arms’ depots found in Haftar-controlled Libyan oil terminals” Libyaobserver, Tripoli, June 2018. Available at: https://www.libyaobserver.ly/news/revealed-uae-egyptian-arms-depots-found-haftar-controlled-libyan-oil-terminals

7 MALSIN, Jared y SAID, Summer “Saudi Arabia promised support to Libyan warlord in push to seize Tripoli” Wall Street Journal, New York, April 2019. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/saudi-arabia-promised-support-to-libyan-warlord-in-push-to-seize-tripoli-11555077600

8 Final report of the Panel of Experts on Libya established pursuant to Security Council resolution 1973 (2011) November 2019. Available at: https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/S_2019_914.pdf

9 ALLAHOUM, Rammy “Libya’s war: who is supporting whom” Al Jazeera, Doha, January 2020. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/01/libya-war-supporting-200104110325735.html

10 DAOU, Marc “Libya nations divided over support for rebel commander Haftar” FRANCE 24, Paris, March 2019. Available at: https://graphics.france24.com/haftar-libya-international-support/

11 BROWNE, Ryan “Trump praises Libyan general as his troops march on US backed government in Tripoli” CNN, Atlanta, April 2019. Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/2019/04/19/politics/us-libya-praise-haftar/index.html

12 ERLANGER, Steven “With Libya still at war, EU agrees to try blocking weapons flow” NY Times, New York, February 2020. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/17/world/europe/libya-eu-arms-blockade.html

13 Agencias “El Parlamento de Turquía aprueba el envío de tropas a Libia”. El País, Madrid, January 2020. Available at: https://elpais.com/internacional/2020/01/02/actualidad/1577978553_651243.html

14 WEHREY, Frederic “A Minister, a General, & the Militias: Libya’s Shifting Balance of Power” The New York Review of Books. NYBooks, New York, March 2019. Available at: https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2019/03/19/a-minister-a-general-militias-libyas-shifting-balance-of-power/

15 “Statement by Ghassan Salame, Special Representative of the Secretary General to Libya and Head of UNSMIL Pursuant to Human Rights Council Resolution 37/45” United Nation Support Mission in Libya September 2018. Available at: https://unsmil.unmissions.org/statement-ghassan-salame-special-representative-secretary-general-libya-and-head-unsmil-pursuant

16 STEPHEN, Chris “Libya’s oil caught in the middle”. Petroleum Economist, London, October 2019. Available at: https://www.petroleum-economist.com/articles/politics-economics/middle-east/2019/libya-s-oil-caught-in-the-middle

17 ESCRIBANO, Gonzalo “Europa debe evitar que Haftar controle el petróleo de Libia y su Banco Central” Blog Real Instituto del Cano. El Cano, Madrid, May 2019. Available at: https://blog.realinstitutoelcano.org/europa-debe-evitar-que-haftar-controle-el-petroleo-de-libia-y-su-banco-central/

18 FUENTE COBO, Ignacio Libia, la guerra del General Jalifa Haftar, IEEE, Madrid, September 2017. Available at: http://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_analisis/2017/DIEEEA70-2017_Libia_Guerra_General_Haftar_IFC.pdf

19 DE BRUIJNE, Kars “Challenging the assumptions of the Libyan conflict” Clingendael, The Hague, July 2017. Available at: https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/2017-10/crisesalert-1-challenging-the-assumptions-of-the-libyan-conflict.pdf

20 ROSELLO, Daniel “Los tuaregs libios” El Orden Mundial, Madrid, May 2016. Available at: https://elordenmundial.com/los-tuareg-libios/

21 WESTCOTT, Tom “Feuding tribes unite as new civil war looms Libya’s south” Middle East Eye, London, February 2019. Available at: https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/feuding-tribes-unite-new-civil-war-looms-libyas-south

22 TOALDO, Mattia “Petróleo y política en la Segunda Guerra Civil Libia” Estudios Política Exterior, Madrid, March 2015. Available at: https://www.politicaexterior.com/articulos/afkar-ideas/petroleo-y-politica-en-la-segunda-guerra-civil-libia/

23 GHADDAR, Ahmad “Exclusive: Libya oil exports threatened as NOC warns against port deal”. Reuters London/Tunis, July 2016. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-libya-oil-exports-exclusive/exclusive-libya-oil-exportsthreatened-as-noc-warns-against-port-deal-idUSKCN1040DO

24 SHENNIB, Ghaith “Libyan Berbers shut gas pipeline to Italy, cut major income source” Reuters, Tripoli, November 2013. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-libya-gas/libyan-berbers-shut-gas-pipeline-to-italy-cut-major-income-source-idUSBRE9AA0UT20131111

25 AFP “Tunisian oil workers kidnapped in Libya have been freed, says consul”. France24, Paris, February 2019. Available at : https://www.france24.com/en/20190217-tunisia-oil-workers-kidnapped-libya-freed

26 TURAK, Natasha “Libya’s biggest oil field is being held hostage, but even that won’t boost prices”. CNBC, New Jersey, December 2018. Available at: https://www.cnbc.com/2018/12/18/libya-biggest-oil-field-is-being-held-hostage.html

27 PEARSON, John “Libya militias battle for control of oil ports”. The National, Abu Dhabi, December 2016. Available at: https://www.thenational.ae/world/libya-militias-battle-for-control-of-oil-ports-1.204610