Africa: expectations and reality

«Si l’Afrique peut se définir au singulier, elle doit se composer et se décliner au pluriel. Je ne crois pas me tromper en disant que son passé est encore indéfini, son présent est moins que parfait et son futur est au conditionnel » (Louis Sabourin, Un demi-siècle d’Independence en Afrique, Québec, 2010)

("While it is true that Africa can be defined in the singular, it must be described and declined in the plural, while its past is yet to be defined, its present is not perfect and its future is conditional" Professor: Louis Sabourin, Half a Century of Independence in Africa, Quebec, 2010)

The African Development Bank is a multilateral bank created in 1964 that currently has 80 member countries (54 regional and 26 non-regional). Its main objective is to promote sustainable economic growth and poverty reduction in Africa. Its headquarters are located in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire.

Light up and Power Africa; Feed Africa; Industrialize Africa; Integrate Africa; and Improve the Quality of Life for the People of Africa. These focus areas are essential in transforming the lives of the African people and therefore consistent with the United Nations agenda on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Around these five priorities there are many other factors that determine the present and future of the continent. This document seeks to summarise these factors without concealing the reality of the various African countries, since, let us not forget, Africa is a group of countries with differences in terms of ethnicity, geography and political and economic model.

The changes that this continent has undergone over the years in its development management have resulted in a shift from marked Afro-pessimism to exaggerated Afro-optimism. The latter is motivated by questionable growth. According to the AfDB, between 1981 and 2008 African GDP per capita declined by 15%, but in 2015 the same agency claimed that Africa was on the verge of real economic growth with an average rate higher than that of the rest of the world (3% for the world economy and 4.7% for Africa in 2013). However, African growth today still relies on the tripod of raw materials, official development assistance and debt relief for a number of heavily indebted poor countries ( a growth which is still of poor quality, with Africans celebrating the potentials rather than the results).

In Africa, many factors of all kinds converge: political, economic, social, financial, geographical, etc., which encompass a very extensive puzzle of terms that only the treatment of each of them would take many pages and that is not the purpose of this document. In any case, it is convenient to list them in order to realise what this continent gives of itself when it comes to analysing it; and they would be Natural resources, transformation and industrialisation, diversification, geographical areas, intraregional trade, youth, middle class, demography, urbanism, agriculture, energy, infrastructures, climate change, governance, institutions, corruption, illicit flows, security, remittances, conflicts, country risk, financing, ease of business, China, Official Development Assistance ,Foreign Direct Investment, ethnicities, languages, poverty, diseases, foreign debt, colonisation and decolonisation, economic areas, GDP and GDP per capita, AfDB, World Bank, etc. All these terms and some more are the constant DNA of this region. Only this continent would provide a degree in economics per se in any university. It is true that, unlike a few years ago, Africa is more often mentioned and featured in the specialised media. Unfortunately, the continent continues to be portrayed in other media as an area of risk and conflict, presumably out of ignorance, and ignoring other more promising aspects that also exist and should be recognised, as these would invite companies and governments to focus on this part of the world as one of their strategic priorities.

What would be the main aspects that Africa should work on to achieve a sustainable development path3 over time: 1. Good governance and better institutions. 2. Development of macroeconomic management in accordance with the characteristics of the continent and its countries (Do not unconditionally follow the messages of non-African leaders and institutions. There is still a dominant tendency to tell Africans how to do things and this is still not working) 3. Education and training (mention: young population).

The best treatment and approach to these three points will allow Africa to be a benchmark region in the future, and these aspects will be developed further in this document.

Good governance is the insurance of those who invest. Good governance reassures those who start an investment process, as well as those who trade. We already know that the higher the rate of good governance, the greater the flow of investment, whether domestic or foreign, and so we should analyse what the main characteristics of good governance should be and what is happening in Africa in this respect. In their book 'Why Nations Fail', Daron Acemoglu and Jim Robinson state that it is economic and political institutions that underlie the success or failure of countries.

A solid regulatory framework, guarantees for investment, transparency, institutional and political stability, and a low corruption ratio mainly in the administration.

Underdeveloped countries are characterised by a highly interventionist institutional framework when it comes mainly to their laws, given that the administration is not only inefficient but also corrupt, which not only hinders production and development but also discourages investment. Poor economic institutions allow and facilitate greater political control and the maintenance of elites in power. In short, so-called "institutional poverty"; and this contributes directly to the overall poverty of countries. This institutional dynamic has been a feature of many African countries and continues to be so in some since independence.

"In most African countries, immediately after independence, a situation was reached where, in order to maintain control of the apparatus of power and wealth creation, political leaders found it 'cheaper' - a smaller share of scarce public resources - and safer to distribute private goods and use coercive means to provide public goods and win electoral support".

(Carlos Sebastián: 'Underdevelopment and Hope in Africa')

In Africa, some countries have followed practices of control regimes by the administration itself in terms of its intervention in a variety of economic decisions ranging from intervention in the companies themselves, in relation to pricing, to the distribution and marketing of products, and access to credit (only for some power-minded). And it was in the countries that followed these practices that economic growth was lowest, if not low. It is also true that those who abandoned this policy and improved their institutions at the end of the 20th century, registered a greater acceleration in their growth rate regardless of the positive effects of the increase in the price of their natural resources, or raw materials. Some examples would be Mauritius, Botswana, Rwanda, Ghana, Ethiopia, Namibia, Tanzania, recently Ivory Coast, countries not particularly endowed with important natural resources.

When we talk about governance and institutions one of the many wise African proverbs comes to mind......

"When elephants fight each other, it's the grass that suffers the most"

Political parties without an ideological base make the political game a battle of the big bosses, with the consequences that this implies. That battle is fought to the detriment of the rule of law and with a very versatile respect for constitutional rules; the imperative in this case is to remain in power. The relative prosperity resulting from years of growth since 2000 has given rise to the birth of a middle class (African-style, if you like) and if it is maintained and extended in the coming decades, we could expect less DIY governance than we still see today. Perhaps more effective and modern governance.

Good governance promotes equity, participation, pluralism, transparency, accountability and the rule of law so that it is effective, efficient and sustainable. By putting these principles into practice, we will witness frequent, free and fair elections, representative parliaments that draft laws and provide an overview and an independent legal system to interpret those laws. The greatest threat to good governance comes from corruption, violence and poverty, all of which undermine transparency, security, participation and fundamental freedoms. Democratic governance fosters development, devoting its energy to influencing tasks such as poverty eradication, environmental protection, ensuring gender equality and providing sustainable livelihoods. It ensures that civil society plays an active role in setting priorities and voicing the needs of the most vulnerable sectors of society.

"In fact, properly governed countries are less likely to suffer from violence and poverty. (Mo Ibrahim Foundation)

The struggle for democracy in Africa has made the mistake of concentrating efforts on the conquest of political and civil rights, i.e. of obtaining the election of leaders by direct universal suffrage. Free and democratic elections should not sum up everything that a democratic system should contain. In other words, political democracy must be accompanied by economic democracy. Otherwise, everything comes down to a system with false appearances of pluralism observed in free expression, in the holding of democratic elections, sometimes dubious, while the production centres that support the economy are still under the control of the local elite and foreign power. It is at least at this level that the whole key to the debate on democracy in Africa lies.

It is correct to say that developing countries could significantly improve their economic performance by strengthening their institutions. To take the African example, if the average quality of African institutions were to catch up with that of Asian developing countries, income per capita in the region would increase by 80 per cent, from an average of USD 800 to over USD 1,400, according to IMF estimates.

To conclude this chapter, we could say that if African economies are to keep growing, their citizens must have the necessary incentives to become more productive and efficient, the latter being directly conditioned by an adequate institutional framework.

Returning to the previous point, good macroeconomic management requires good governance and appropriate institutions. Among other aspects, Africa needs to avoid wasting its enormous natural resources, and this requires vision, transparency and technical capacity in the management of the economy.

Sub-Saharan Africa continues to recover economically according to the IMF's April 2019 analytical summary. About half of the countries in the region, especially the poorest in natural resources, are expected to grow at 5 per cent, while resource-rich countries are expected to grow less and much more slowly. Since these countries, of which Nigeria and South Africa are part, account for about two-thirds of the region's population, it will be important to focus on addressing the policy uncertainties that are holding back growth in order to improve the standard of living of their people.

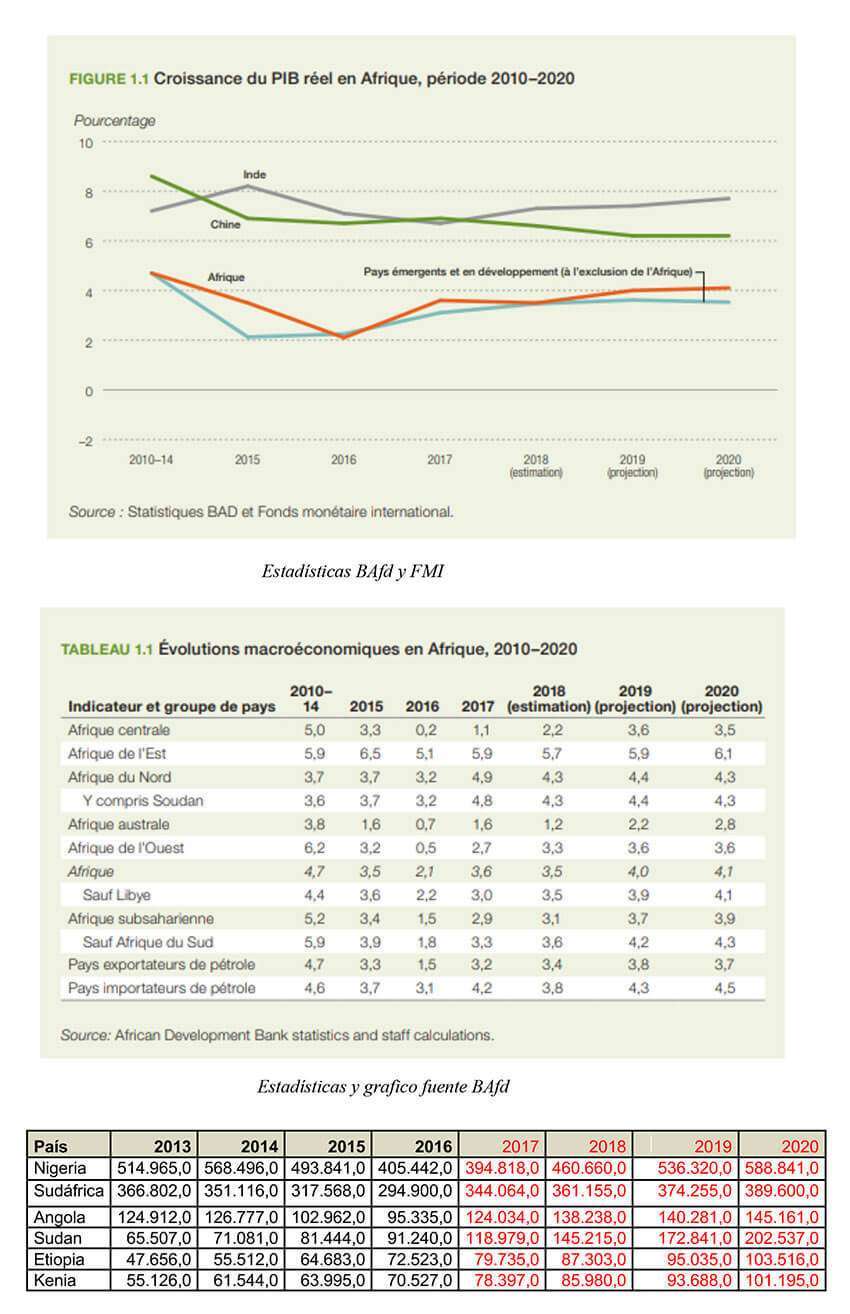

With a lower external environment, the projected growth rate for Sub-Saharan Africa, according to the IMF, will rise from 3 per cent in 2018 to 3.5 per cent in 2019 and 3.7 per cent in 20207 (see chart 1.6 IMF). Twenty-one countries with a diversified economy will grow at a rate of 5 percent with a per capita GDP in line with the good progress made since 2000 (weighted with GDP in purchasing power parity (PPP), see chart 1.1 IMF).

On the other hand, according to this organisation's forecasts, growth will be anaemic in the short term for another group of 24 countries especially endowed with natural resources, among which Nigeria and South Africa are in the front line, as I mentioned earlier, and the standard of living of their inhabitants will therefore improve more slowly.

To sum up, according to these data (and this is not new), many African countries are growing very rapidly but are growing poorly, have poor quality growth and are highly dependent on the market price of their natural resources (oil, gas, minerals, etc.), and it is those that have not diversified their economies that are most exposed to the ups and downs of the export prices of their products. Here we could bring to light many of the black holes of growth in Africa. As Carlos Lopes rightly states8 in his book Africa in Transformation:

"Economic growth alone has proved insufficient for Africa's transformation. Despite its vast natural and human resources, poverty and inequality have continued to persist while some analysts question whether this resource curse defines the continent (see The Economist,2015: Why Africa is becoming less dependent on commodities) Jan 11th 2015, 23:50 BY C.W.

Carlos Lopes (1960, Guinea Bissau) is currently a professor at the Mandela School of Public Governance at the University of Cape Town and a visiting professor at Sciences Po in Paris. Previously, he was Executive Secretary of the Economic Commission for Africa, with the rank of Under-Secretary-General of the United Nations, in September 2012.

According to Lopez, this African take-off must therefore be put into perspective and the high rates of GDP growth, as well as other indicators, are only partial and snapshot pictures. Transformation is the key, as Lopes suggests "Africa is growing very fast and transforming very slowly".

In this second point I intend to analyse very briefly some aspects which I believe have a very direct influence on the macroeconomic management of the continent and would be:

Economic integration processes

External debt sustainability/ financing

Foreign direct investment and ODA

What is Africa's biggest growth challenge?

« La croissance est bonne mais, pour réduire la pauvreté, il faut changer la nature de cette croissance ».

Growth is good, but in order to reduce poverty, the nature of this growth must be changed.

(Luc Christiansen chief economist for the Africa region at the World Bank)

To ensure that these growth rates are in fact due to a dynamic and productive economy means that they do not depend on a good harvest or an increase in the price of their raw materials on the markets but on knowledge, specialisation and technology. If we want to have a realistic view of this factor, there are three elements we must not lose sight of:

The African growth curve over a long period of time 2003-2008 was constructed as a consequence of the increase in prices (by definition fluctuating) of raw materials, such as oil and gas, and is therefore fragile and above all artificial.

This growth is not homogeneous given the differences between oil and gas producing countries and the rest. Examples of studies in Algeria and Nigeria: hydrocarbons can inflate growth curves, but they do not prevent the economic and social failure of their peoples.

The African economy -now less so- has not experienced diversification or industrialisation through the transformation of its resources and is therefore less inclusive.

The reasons for economic growth are diverse9, but they include technical progress, investment and the accumulation of capital, both physical and human capital. Opening up to foreign markets also plays a role and the characteristics of what is known as the institutional framework are of outstanding importance: in essence, maintaining a minimum number of essential elements in terms of physical and legal security, peace and freedom. All this continues to be a pending subject in many African countries.

Examples of fragile growth would be Nigeria, Algeria, Angola, Mozambique, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Central African Republic, DRC, Zimbabwe, and perhaps South Africa.

Note that all of these are endowed with significant natural resources including mineral and agricultural resources. We have already pointed out the causes, which are the fixation on the development and exploitation of their main product (abuse of the mono-product) without taking into account policies of diversification, bad governance, fragile institutions, political and social conflicts, high corruption, capital evasion, etc., among others.

Did we think that the income from oil and minerals was eternal, not knowing how cyclical the market for raw materials is? Could it be that there has been uncontrolled growth over the last 10 years in Africa, specifically in those countries that produce oil and minerals? Has this growth been a symptom of development throughout the continent? Have necessary structural reforms of the economy been made to take advantage of this long period of growth? Is inclusive growth taking place? All these questions and others are not new, many analysts have denounced them over the years, but others have forgotten them.

We have already forgotten the Afro-pessimism of the 90s, but have we committed a sin of Afro-optimism? Or do we have to take on board what Africa is; a mosaic of countries with unequal resources and behaviours and start to realise that the most appropriate term for the continent is Afro-realism, that is, to adopt an honest look at the continent, to be aware of its past and the global environment in which it is immersed as well as the enormous challenges it has ahead of it. We could conclude by saying that if countries do not save, and do not manage their income properly during periods of expansion, they will have little capacity to react when the prices of raw materials fall and they will have no choice but to be austere, and this will therefore put a brake on growth.

Recipe: Diversify to minimise risks, since we should not forget that basic products account for over 60% of merchandise exports in some 28 African countries according to a UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) report.

Other countries in the sub-continent –not necessarily endowed with significant natural resources– have been setting an example for years of coherent10 and more sustainable economic management, as is the case with Botswana, Cape Verde, Ivory Coast, Ethiopia, Mauritius, Kenya, Namibia, Rwanda, South Africa and Djibouti. To which I would add Morocco in North Africa.

On the other hand, it is important to highlight the technological change that has allowed Africa to skip some traditional stages of development. Mobile telephony has penetration rates not far from those of advanced countries, without having to invest in expensive land-based telephone networks.

By 2025, half the population of sub-Saharan Africa will have subscribed to the services of mobile operators. At the end of 2018, Sub-Saharan Africa had 456 million single mobile subscribers, an increase of 20 million from the previous year and a penetration rate of 44 per cent. About 239 million people, or 23 per cent of the population, also use the mobile internet on a regular basis.

Sub-Saharan Africa will remain the region with the highest growth rate, with a compound annual growth rate of 4.6 per cent and another 167 million subscribers by 2025. This will bring the total number of subscribers to just over 600 million, or about half the population. By 2025, Nigeria and Ethiopia will have the fastest growth rates of 19% and 11% respectively. Across the region, the population boom will lead many young people to equip their mobile phones for the first time. This segment of the population will represent the majority of new mobile subscribers and, as "digital natives", will have a significant impact on how different mobile services will be used in the future.

Geography, trade and infrastructure are closely linked when we talk about Africa. In many African countries productivity is low, mainly due to the poor geographical proximity between their economic agents, and this proximity, which is adverse, has two dimensions:

On the one hand, the lack of proximity between African countries and international markets and, on the other, between the different economic agents within Africa due to an insufficient agglomeration of economic activity. African geography undoubtedly influences proximity and productivity and this is reflected in transport costs. I would like to highlight some preliminary data to understand this geography: The African continent today has some 83,500km of political land borders, drawn in a short quarter of a century (1885-1909). These chancellorial borders were established by Europe on unrecognisable maps and, above all, without any prior recognition of the terrain. Sub-Saharan Africa today is a mosaic of political entities with very large areas (Democratic Republic of the Congo) and very small areas (Burundi), very arid (Niger) or too enclosed (Central African Republic) to form coherent economic enclaves. The African continent is very complex and it is not possible to approach it as if it were a homogeneous whole. There is no single Africa. The difficult geography of Africa's economy represents a major challenge for the development of infrastructure and trade in the region. Some characteristics of this geography that inevitably condition the viability of infrastructures could be:

The low overall population density, with 36 inhabitants per km2

The still weak urbanisation rate (35%)

A significant number of countries from the interior of the continent, with very small economies and with still little intra-regional connectivity and few cross-border connections that are favourable to regional trade.

A World Bank report published in April 2012 entitled "The Fragmentation of Africa" identified the main obstacles to the development of trade between the various regional groupings (COMESA, ECOWAS, WAEMU, etc.): Transaction costs, non-tariff barriers, and different immigration procedures. In addition, there is a growing number of informal cross-border exchanges (which account for more than half of official flows, mainly in West and East Africa).

The thickness of the borders in Africa greatly increases trade costs. The costs associated with transport and logistics for the movement of goods are part of this border thickness, and this is precisely what weighs on the establishment of a given region of the continent. The liveliness of Africa's borders is fuelled by trade in basic products, more or less legal trafficking, and fraudulent flows, as well as institutionalised smuggling. A whole world lives from these border asymmetries (traders, transporters, customs officers and military) and tens of millions of inhabitants live on these borders. I therefore wonder about the veracity of the official statistics, if we consider the economy as it works and not just the formal economy, since there are many areas where trade is made fun of borders.

Firstly, a necessary rapprochement between the transit corridors in order to promote internal and external trade with a greater and better provision of logistics and transport services. Next, greater regional integration efforts. The necessary legal and regulatory reforms, greater commitments from the administration and institutions in general, and a greater provision of infrastructure to enable the countries of the interior to develop multimodal trade services (rail, road, air, etc.). The fact is that Africa is currently trading better with the rest of the world than with itself.

Regional integration has been an aspiration of the various African states since the time of Africa's independence. And this need for regional integration has been strengthened by the current process of globalisation in which regional blocs reign. Therefore, it is integration, particularly its economic aspect, the necessary vector of African development.

The reality today is that regional integration is a pending issue in Africa and progress over the past 50 years has been very slow. Africa accounts for approximately 3% of world trade; while trade between Europeans has reached 70%, that of the Asian dragons 50% and that of Latin America 21%, this falls to 11% when we talk about Africa11.

"When African countries trade with themselves they exchange more manufactured and processed goods, have more knowledge transfer, and create more value”

(Vera Songwe, Executive Secretary of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa)

In 2018, AU member countries (44 out of 55) gave a major boost to regional trade and economic integration by creating the Continental Free Trade Area for Africa, or AfCFTA, with commitments to abolish customs duties on most products, liberalise trade in key services, and tackle non-tariff barriers to intraregional trade and ultimately create a single continental market where labour and capital can move freely. It is intended to come into force this year to give rise to a market of 1,200 individuals representing $2.5 billion of accumulated GDP. It has already been ratified by 22 countries, which was the required number.

The reality must be told: sub-continental economic integration in Africa is in the process of being worked out and is progressing very slowly and not without great difficulty. The main explanation lies in the scant interest of some African elites in member countries reluctant to change the 'status quo' that favours them. As José Ramón Ferrandis points out in his book 'Africa es así', the case of Nigeria is very African-like. In July 2018, Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari finally announced that he would sign the AfCTA. Regarding his delay, he said "I am a very slow reader maybe, because I was a soldier. I didn't read it fast enough before my officials saw that it was all right for signature. I kept it on my table. I will soon sign it," he added. According to Ferrandis, this treaty is also very optimistic, especially considering that the list of products (goods) and commitments on services to be negotiated are not yet known, in addition to the already slow procedures in Africa.

It is true that intraregional trade has evolved favourably in recent years. In 2017, parts of intraregional trade have taken place within the framework of the main sub-regional communities, and it should be noted that, unlike the rest of the world, these flows are more diversified in terms of their products and have a higher added value with a significant weight of manufactured products (cars and textiles, for example). In short, it would be desirable to concentrate efforts firstly on overcoming non-tariff barriers in order to achieve valid regional trade integration, by which I mean overcoming the mediocrity of trade logistics and the lack of infrastructures.

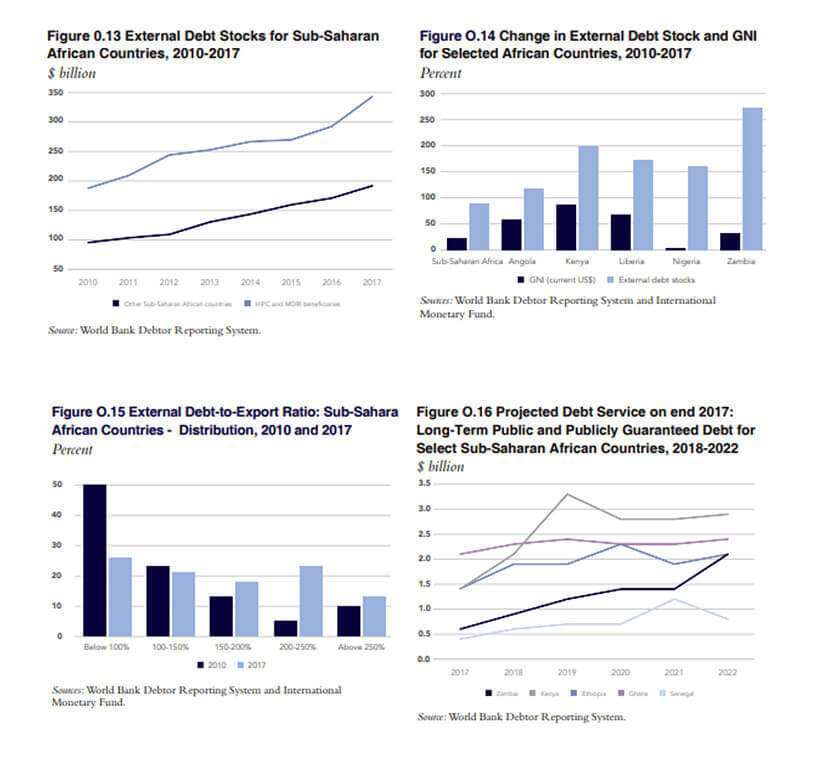

Among the various economic features of the subcontinent, it is worth mentioning the region's growing external debt, as well as its financing needs.

Are we reaching unsustainable levels of debt?

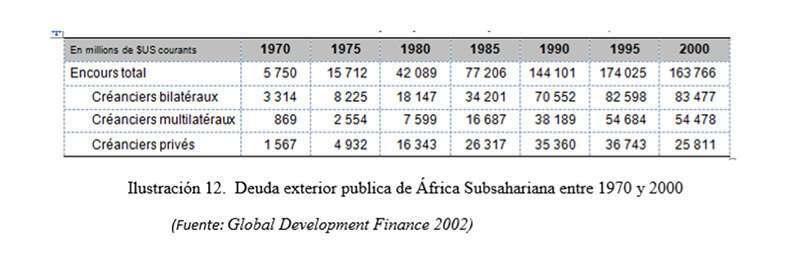

As for most developing countries, the external debt of Sub-Saharan Africa accumulated massively during these years in an international context favourable to indebtedness, with Western banks having significant liquidity (petrodollars) together with low interest rates, and a policy of revival in the industrialised countries facilitating credit to the countries of the South combined with a rise in the price of raw materials, as a sufficient guarantee for debt repayment. This is why between 1970 and 1980 the foreign debt (debt contracted by the state, by a public company or by a private company with a state guarantee) of developing countries increased eightfold from USD 47 billion to USD 381 billion. Sub-Saharan Africa's debt increased by almost the same proportion (USD 41.9 billion in 1980 against USD 5.8 billion ten years earlier) with annual growth rates of 20% to 30%. This massive supply of credit is accompanied in Sub-Saharan Africa, as in other countries, by large-scale corruption. In short, it is a flight from debt. This is the era known as that of the "white elephants" and the "cathedrals in the desert" .

Examples of these lavish years can be seen in characters of the stature of Bokassa, Mobuto, Idi Amin Dada etc....

The pincer crisis (a combination of falling commodity prices – oil, minerals, coffee and cocoa – and rising interest rates on a global scale somewhat similar to what is happening now) brought the continent to a long period of stagnation.

Financing that seemed a miracle solution in the 70s becomes impossible in the 80s.

Mexico's default on debt leads to a drastic reduction in credit in 1982.

The increasing debt service (the payment of interest on the debt) clearly affects the finances of the states and destroys the national budgets.

Investment rates drop sharply from 20% to 15% leading to net decapitalisation in African economies and weak investments are insufficient to compensate for the serious deterioration of infrastructures, and development aid is less and less directed towards investment.

It is at this point that the Bretton Woods institutions issue a terminal diagnosis: Given the crisis situation of African economies, they are forced to structure themselves and for this purpose the well-known SAPs are created: Structural Adjustment Programmes (liberalisation and deregulation of the economy and against state intervention). These institutions, influenced by the Thatcher-Reagan neoliberal consensus, marked the policy to be followed in these years, which was ultimately based on the search for budgetary balance, drastically reducing public spending even in social sectors, abandoning redistributive bureaucracy, ceasing price subsidy practices, giving priority to repayment of foreign debt and privatising public companies, in short, shock therapy.

Paradoxically, the main victim of German reunification was Africa. With the fall of the Berlin Wall, the continent lost its status as a terrain of ideological, economic and military confrontation between the capitalist and socialist blocs. In those years, the priority was elsewhere, precisely in Eastern Europe, and aid to Africa began to be converted into transfers and donations of a solidarity nature which were privatized or externalized and taken away by the NGOs which were in full swing at that time.

This change of record led to a significant decline in ODA (official development assistance) from $34 per capita in 1990 to $21 in 2001. The reality is that in the 1990s there was a lack of commitment to the continent and Africa was only worth pitying. Africa in the 1990s could be defined in terms of Afro-pessimism.

Economic Africa entered the 21st century with an important injection of cure into its public debts.

African countries benefited from the G7 initiative in 1996, which was later reinforced in 1999 with a significant reduction in their bilateral and multilateral debt. The joint and comprehensive IMF and World Bank strategy to reduce Africa's debt was intended to ensure that no poor country bears a debt burden it cannot manage.

To date, under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative, debt relief plans have been approved for 36 countries, 30 of them in Africa, which over time would provide US$76.9 billion in debt service relief and US$42.4 billion under the MDRI in present value terms by 2015.

The HIPC and the Multilateral Debt Relief (MDRI) initiatives and the Paris Club initiatives have substantially reduced the debt of completion point countries. The Paris Club is a space for discussion and negotiation between official creditors and debtor countries. Its function is to renegotiate in a coordinated and joint manner the external debts of debtor countries with payment difficulties.

To receive full and irrevocable debt relief under the HIPC Initiative, a country must:

1. Establish a track record of further good performance under IMF and World Bank loan-supported programmes.

2. Successfully implement the key reforms agreed at the decision point.

3. Adopt and implement a Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper for at least one year.

Once these criteria have been met, the country can reach its completion point, which allows it to receive the full debt relief promised at the decision point.

However, attention should be paid to how this phenomenon unfolds over time. A number of HIPCs have fallen back into levels of indebtedness that, for the second time, have caused them to repudiate their debt. The worrying thing is that if they are bailed out again (those that relapse), the debt relief scheme may collapse.

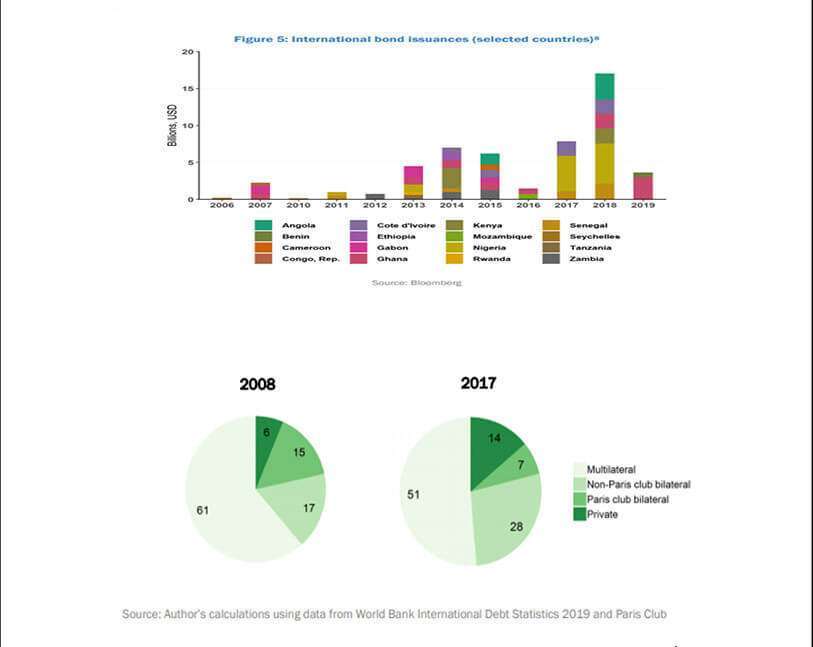

The World Bank currently (most recently in June 2018) reports that 40% of poor countries have a level of public debt that is unsustainable or at high risk of becoming so. This is serious. Public debt was 45% of GDP in 2017 and in addition 11 of its LDCs (least developed countries) are at serious risk of over-indebtedness. With commodity prices still not picking up clearly and official development assistance (ODA) under review, many African countries have resorted to debt issuance. As the debt is denominated in foreign currency, (much of) any possible depreciation of the local currency (which always occurs) can prolong the agony of debt repayment.

In addition, estimated illicit capital flows remain massive. As a result, Africa has been a net creditor to the rest of the world. While it is difficult to measure illicit resource flows from Africa, several estimates suggest that they are between $50 and $60 billion per year. Illicit resource outflows are enabled by internal governance failures and corruption, as well as by the practices of multinationals engaged in tax evasion and profit shifting (UNECA, 2015). On the positive side, there is a growing movement to reverse resource outflows through a combination of improvements in internal governance, including anti-corruption measures, as well as capacity building for tax administration and resource management.

We cannot fail to include China in this section. China is the continent's largest aggregate importer and this is important because its demand drives the prices of many strategic minerals. In other words, if China's demand increases prices rise and African exporters celebrate, but if the opposite happens...

China has also been Sub-Saharan Africa's largest bilateral lender in recent years. China is particularly prominent in financing various infrastructure projects. Based on data from the China-Africa Research Initiative (CARI), China committed $125 billion in loans to sub-Saharan African countries between 2000 and 2017. Chinese lending to the region has accelerated since 2012 to about $10 billion each year from an average of $5 billion between 2005 and 2010.

Angola has been the largest recipient of Chinese loans, accounting for one third of Chinese loans in Africa. Ethiopia and Kenya complete the top three destinations for Chinese loans, with 11% and 8% respectively. During the 2018 China-Africa Cooperation Forum, China committed an additional $60 billion in African financing over the next three years, mainly in the form of loans.

Despite the increase in Chinese lending to Africa, China is not a majority holder of external debt in most countries. According to a recent analysis of CARI data, China holds the majority of external debt in only two of the countries with or at risk of debt problems, namely the Republic of Congo and Zambia (Chinese loans in the two countries amount to about $14 billion, representing just over a tenth of its total lending on the continent).

In the long run, the results for African countries (not their leaders) are and will be very negative as their debt to China far exceeds their ability to repay. These countries would be out of the control and macro schemes of the IMF so their loans would be in Chinese hands with the possibility of increased conditions for new loans (which would be leonine).

To conclude on this point, the relationship with China has additional advantages. Chinese companies are not subject to political, social, or corruption issues, and there is no body interested (perhaps the OECD to which they do not belong) which is very convenient for African decision makers: the Chinese have their hands free to enter the dark zone and Chinese companies do not have to submit to environmental restrictions.

It would be advisable to deepen the combination of cooperation + investment more in line with current African times. There is no country in today's globalised world that does not promote foreign investment in its own country in one form or another. In theory, FDI is therefore a factor in development aid. Local African investments alone cannot achieve the growth of their economies and capital investment from foreign investors is one of the most effective ways of building many of the necessary infrastructures in Africa.

Such investors and foreign investments are labour intensive, and FDI in most cases provides job opportunities for locals, as well as knowledge and development transfer to the host country. Not only that, but also, from an economic and social point of view, the payment of taxes by foreign investors and, consequently, their obligatory contribution to national budgets.

However, all of this would only be effective if it was properly managed. Development is not just a question of money, otherwise Africa would have already solved its problems, since since the OECD countries have devoted more than 650 billion dollars to this concept or to the development of the continent, yet ODA has increased on this continent in the same proportion as poverty. It distorts international financial flows and generates a moral risk, i.e. a tendency for one party to take risks because the possible costs of the risk of a disaster will fall not on that party but on others. (taxpayers, depositors, other creditors etc.) It should be seen how many banking crises have had to be resolved because of the recovery paid by taxpayers. In cooperation and investment, there are no definitive recipes; in any case, both are necessary and each of them fulfils a function.

There are political, economic, social and certainly cultural reforms that need to be carried out, starting with overcoming the culture of dependence, and it is Africans themselves who are denouncing this. In any event, let us not forget that no Third World country has developed on the basis of aid, and it can even be counterproductive if it encourages mismanagement and corruption among the beneficiaries or the strengthening of local dictatorships, as occurred in previous decades.

Europe's paternalistic position still persists on the African continent; it is a European vision of Africa as a humanitarian burden. One of the most notable characteristics of European investments and Europe's commitment in general to Africa, and more specifically to sub-Saharan Africa, is based on the conception of the region as an economic burden. This is precisely why Europe is focusing more on providing the continent with development aid and less on trade and investment commitments. Europe has begun to realise that this is not the way forward.

Today, in the 21st century and more so in the case of Sub-Saharan Africa, this kind of commitment is simply not sustainable, creating economic imbalances and making many African economies dependent on NGOs and European governments themselves. To become an economic partner, the EU must do more to reinvest this equation by focusing more on trade and investment, as this would reduce the need for development aid from the EU, European governments and European NGOs. Europe cannot, because of tradition, proximity and history, afford to lose Africa to other competitors such as Chinese, Indians, Turks, Brazilians, Moroccans, etc.

« Parmi toutes les régions, l’Afrique subsaharienne a les taux les plus élevés d’exclusion de l’éducation. Plus d’un cinquième des enfants âgés d’environ 6 à 11 ans n’est pas scolarisé, suivi par un tiers des enfants âgés d’environ 12 à 14 ans. Selon les données de l’ISU, près de 60 % des jeunes âgés d’environ 15 à 17 ans ne sont pas scolarisés.

Si des mesures urgentes ne sont pas prises, la situation empirera certainement, car la région fait face à une demande croissante d’éducation en raison de l’augmentation constante de sa population d’âge scolaire. » UNESCO 2019

"Of all regions, sub-Saharan Africa has the highest rates of education exclusion. Over one-fifth of children between the ages of about 6 and 11 are out of school, followed by one-third of youth between the ages of about 12 and 14. According to data from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), almost 60% of 15- to 17-year-olds do not attend school. If urgent action is not taken, the situation will undoubtedly worsen as the region faces a growing demand for education due to the steady increase in its school-age population". UNESCO 2019.

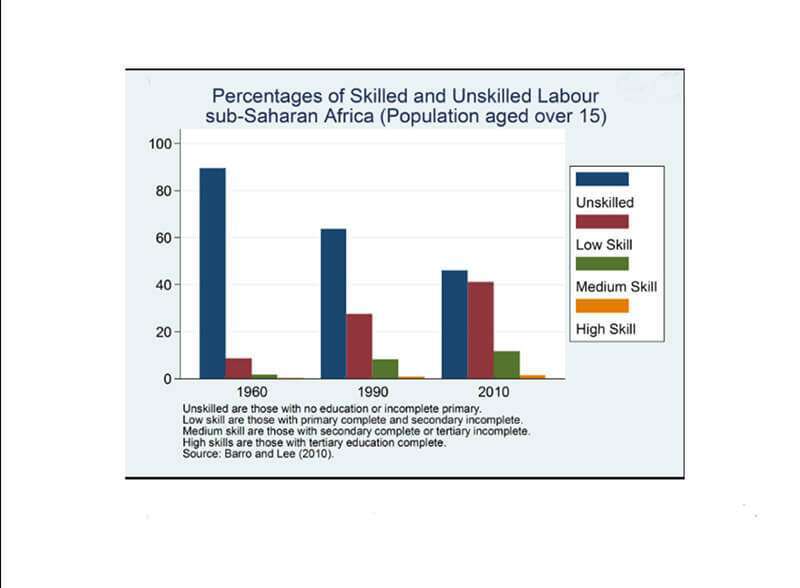

Educational backwardness is a marked feature of the African reality and surely a cause or consequence of the region's underdevelopment. However, there has been an increase in the rate of education in recent decades. Today, World Bank statistics, as well as those of UNESCO, show increasing progress in years of schooling (years of education) and one consequence of this has been higher literacy rates. So says Carlos Sebastián in 'Underdevelopment and Hope in Africa' (Galaxia Gutenberg).

That said, there are still African countries with significant educational deficiencies and the corresponding illiteracy. The net primary school enrolment rate has grown overall in Africa by about 12 points during the 2000s to reach 75% by 2015. The secondary school enrolment rate has increased by 10 points to 35 %. School enrolment has increased by 31 % and Africa spends 5 % of its GDP and 20 % of its budget on education, but despite this quantitative progress, more than 40 million African children are still out of school, with significant dropouts among boys and girls (9 %).

If we compare the reality of education in Africa with that of the other continents and sub-continents, black African countries are at the bottom, which is a determining factor. The lack of qualified human capital, in a technified world that demands knowledge like today's, is a guarantee of failure. This illiteracy has a very negative effect on the availability of human capital prepared to carry out economic activity other than survival.

All these factors affect the majority of the child population with the resulting future consequences for African youth, because Africa is a young continent. One third of the world's population is under the age of 20. Some countries have more young people than others. In about 40 African countries, about 40 % of the population is under the age of 20. In contrast, in 30 of the richest countries, less than 20 % of the population is under 20.

"Africa must stop being a museum of poverty. Its people are determined to reverse this trend. The future of young Africans is not in Europe, their destiny is not to perish in the Mediterranean" , Akinwunmi Adesina, President of the African Development Bank, told journalists at the 53rd Annual Meetings in Busan, South Korea, last June.

Sixty percent of Africans are under 24 years old. By 2050, 35% of the world's young people will be African, compared to 15% in 2000. This specificity is an essential fact of the future of this continent, the youngest in the world. In principle, this could be a window of opportunity - as Serge Michailof tells in his book “Africanistan” - for a growth in the potential working population (aged 15 to 64), but in order to benefit from this demographic dividend, young people who arrive massively on the job market must be able to find decent, formal employment with higher productivity than today.

If this young demographic force fails to enter the labour market, we will find ourselves with a huge mass of hopelessly underemployed people both in the countryside and in the city. A significant fraction of Africa's urban youth is that commonly referred to as ni-ni-ni: neither in employment, nor in search of employment, nor in training. And we already know what this situation leads to: social upheavals and new springs - African ones in this case. As a reminder, young people already make up 60% of Africa's unemployed population.

For example, land and youth are two very abundant resources. Sixty percent of the unused arable land is in Africa, yet many African countries have to import basic foodstuffs. Moreover, young people do not think that agriculture is an attractive life option. As a result, the average age of the Kenyan farmer is 63, and that of the South African is 62. Technical and vocational training in the agricultural sector could provide employment for millions of young Africans, ensure that they stay in rural areas rather than going to live in already overcrowded cities and, above all, ensure food security. But most young Africans are interested in becoming entrepreneurs or working in the service sector, such as banking and telecommunications. Although politics in Africa is still largely dominated by the old guard, it cannot be denied that the continent has embarked on a process of transition of leaders. In this journey, each country will have to set its own pace. And young people will need to be pushed into leadership positions that will enable them to create jobs, run institutions and design, implement and manage policies. For the transition process to be successful, young Africans will have to be an integral part of it. Africa's pre-colonial history shows that, in the past, the continent had important leaders. The kingdom of Mali, the kingdom of Ghana, and the Ethiopian and Nubian civilizations had great influence. Now, young people can lead Africa to prosperity for all in the 21st century.

"Africa's uprising was focused on the opportunities for the world market, not necessarily on the interests of Africa itself". (and there is still much of that today)

('Africa in transformation', Carlos Lopes)

Throughout this document, the different challenges Africa has faced and is currently facing have been described. Africa is still in transit, a continent that was led by the colonising powers and has had the real possibility of directing its own destiny for over a decade. Its potential is huge, as we have already described. Africa must believe in itself; it must be Africans themselves who lead its growth, manage its growing demography and lay the necessary foundations for overcoming the huge challenges ahead. Challenges such as overcoming the infrastructure gap in sectors as necessary as energy and transport and moving towards a technologically transformed agriculture, as it is the sector that produces most labour (Africa spends some US$35bn annually importing food, many of which can be produced on the continent itself. Countries such as Ethiopia and Rwanda are succeeding, but fragile infrastructure, regional barriers to trade, and other factors such as the exchange rate are driving African farmers out of the market). All of this requires a clear political will on the part of those who govern, an intelligent and practical vision of the future in order to be able to at least deal successfully with the better macroeconomic and social development of the continent.

The next few years will be good ones, depending on whether the conditions I have just mentioned are met. Having said this, and given the difficulty of predicting and even more so in the case of the African continent, which is basically a continent exposed to many other external factors such as climate, possible ethnic conflicts, pandemics, poverty and malnutrition of its inhabitants, dependence on foreign markets, etc. I would like to highlight those actions that I believe would channel this territory of more than 30 million km2 into a simply more sustainable future.

First, Africa must grow on a sustainable and supportive basis by increasing productivity in all sectors of the economy and creating quality jobs. To do this, it must undoubtedly transform its economy and it is up to Africans themselves to decide and no longer depend on demand from other mature or emerging markets for further growth. To participate much more in global value chains. Only 3% of the world's export volume comes from Africa and 50% of African exports are processed outside the continent and therefore do not receive this additional value added (export of unprocessed raw materials).

We know that a percentage of the world's export figures for goods and services are supplied by third countries (as is the case with many African countries) and then exported and are therefore double counted in world trade. Africa is becoming poorer in absolute terms in this respect, and the trend must change to greater processing of exports within their respective countries.

A value chain ultimately means a succession of several stages in which a company offers a product or a service from its conception to its final delivery to the consumer. Global value chains offer new opportunities for structural transformation in Africa. Africa must therefore gradually stop being a source of raw materials for many global value chains and create its own "made in Africa" brands.

Second, Industrialisation, since industry is the engine of growth and Africa has a young and abundant labour force, natural resources that are also abundant, and finally an offer aimed at emerging and mature markets, mainly in Asia and Europe. Africa's industrial future will depend on a progressive transformation of its local raw materials, as well as on a basic industry that can be exported to the rest of the world.

Third, addressing the significant lack of infrastructures. Transport and electricity are two veritable pillars on a large part of African territory. Communication between towns, places where goods are produced and centres of sale and consumption must be improved because the development of these would have a very positive impact on the economies of these countries.

Fourth, improving the quality and transparency of public institutions by making the administration more efficient. Although there is an improvement in the quality of governance in some countries there is still a high level of corruption. There are countries such as Botswana, Mauritius, Namibia, Ghana, Rwanda and Ethiopia that score higher and are not necessarily endowed with natural resources. Others such as Nigeria and Angola which are blessed with resources have however an insufficient quality of governance.

Fifth. Let us not forget basic training, as Africa, the continent of the future, cannot neglect this aspect, especially with its essentially young population.

The conclusions for Africa are anything but obvious and difficult to sustain given the potential and at the same time the dependence of this region on global markets. Africa, as I said, is a complex subject, even if it is exciting to study. The legacies of the past in some countries are still hampering growth which, although real, is fragile because it does not generate enough jobs in an essentially young population, the youngest of all nations.

Such growth requires a better approach to the future. A number of African countries, however, have taken off with more coherent policies aimed at further liberalization of their economies, with stronger institutions and better governance. Challenges such as diversification of the economy, increased manufacturing, greater involvement in global value chains, gradually overcoming chronic deficits in physical infrastructure, mainly in the energy sector with greater funding and more innovation, are the challenges that Africa must address.

All of this, moreover, in order to cushion the cyclicality of global economic performance when it is adverse. It is necessary to give wings and space to this huge young African population with tremendous potential, which is calling for a better future and a better way out of its aspirations. But it is Africa itself that must contribute to making this happen.