The balancing act of Turkish foreign policy and the war in Ukraine

This document is a copy of the original published by the Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies at the following link.

In recent decades, Turkey has gone to considerable effort to regain its role as a regional power that can exert influence in its neighbourhood and be a force that must be reckoned with. While trying to maintain a difficult-to-achieve balance among the major global powers, the evolution of events in the unstable regional environment called for an increasing involvement of its military power which, far from obtaining the hoped-for results, ended up plunging the country into undesirable diplomatic solitude. The moderation which, in both form and substance, has characterised the state's external action since the end of 2020 is aimed at remedying this unsustainable situation. In these circumstances, the outbreak of war in Ukraine offers opportunities to capitalise on the complex politics of trade-offs that have caused so many difficulties in the past.

In an IEEE paper published in September 2019 entitled Between East and West: ¿Quo vadis, Turquía? analysed the reasons behind Turkey's apparent shift in strategic alignment, which many interpreted as a break with the Western world1. In our analysis, we concluded that with this change of orientation Turkey was trying to adapt to the new geopolitical reality imposed by the disappearance of the Soviet Union which, while posing new security challenges in its environment, offered magnificent opportunities for the expansion of its influence in geographic areas over which it had historically held sway. The designer of this new foreign policy was Turkish academic Ahmet Davutoǧlu, who had begun his political career as foreign affairs advisor to the then prime minister Erdoğan back in 2002, and ended up as prime minister himself in 2016. Davutoǧlu considered that 'in terms of spheres of influence, Turkey is a country that belongs simultaneously to the Middle East, the Balkans, the Caucasus, Central Asia, the Caspian, the Mediterranean and the Black Sea'2, all areas over which, taking advantage of the ascendancy granted by its Ottoman past, it sought to project its power, essentially in the form of soft power but without renouncing the use, if the situation so required, of hard power resources3.

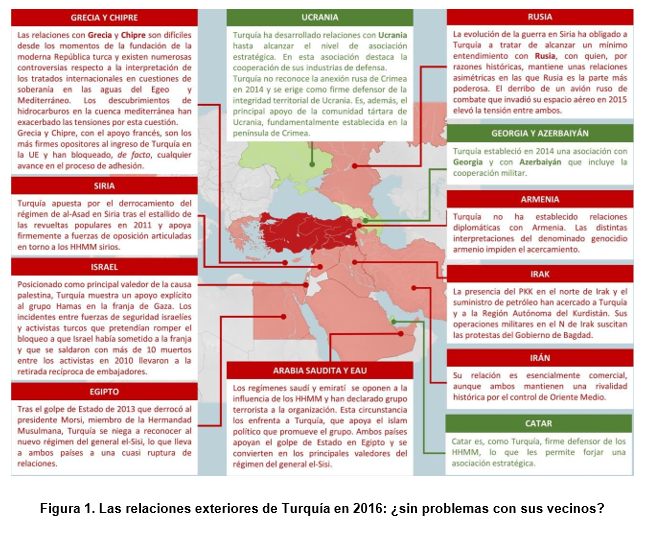

Much was expected of this new, supposedly inclusive policy which, under the slogan of "zero problems with the neighbours", was quickly dubbed neo-Ottomanism. However, despite the good intentions, by mid-2016 there was little doubt that this policy had not yielded the expected results. As the government's critics sarcastically put it, Turkey had achieved "zero neighbours without problems". Since then, Turkey has been trying to get back on top of its foreign policy to reassert itself as an autonomous and independent regional power that can serve as a successful model not only in its regional environment but throughout the Muslim world.

The purpose of this paper is to analyse this process up to the present moment, which is marked by the war in Ukraine. We will begin with a brief description of the state of Turkey's international relations in mid-2016, a clear turning point in its foreign policy, to then study the reconfiguration of the Turkish state's foreign action, which developed in two distinct phases: a first phase that began with Davutoğlu's departure from active politics in mid- 2016, characterised by greater assertiveness in the defence of its interests and greater intervention of military power in the Middle East and the Mediterranean; and a second phase that started at the same time as the changeover in the US presidency at the end of 2020, and is still underway at the time of writing, showing a moderation in forms and objectives that seeks to reduce the negative effects of the previous period. As we shall see, recent geopolitical developments with global impact, such as the war in Ukraine, are giving considerable impetus to this endeavour and, although not without risk, present opportunities for Turkey to revalue its strategic position.

As noted above, for reasons attributable to both external factors and its own mistakes, Turkey's diplomatic successes in its immediate neighbourhood by mid-2016 were, without a doubt, few.

The Middle East was, a priori, the geographical area most permeable to Turkish influence. Cultural affinities, predominantly Muslim populations and the territories' historical membership of the Ottoman Empire were factors that were assumed would work in favour of Turkish interests. However, none of them did, and it is here that the failure of this policy was most evident. One of the most influential issues was the Turkish government's unwavering support for the political Islam represented by the Muslim Brotherhood (HHMM) in Syria and Egypt in the aftermath of the Arab Spring, justified by an obvious ideological affinity. Although the Turkish government's stance was supported by Qatar, with whom it was able to establish a fruitful cooperative relationship, the effects on its relations with the Syrian and Egyptian regimes were extremely pernicious, compromising its relations with the powers that supported them: Russia and Iran in the case of Syria, and the Gulf monarchies of Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in Egypt. But relations were also compromised with Israel, in this case because of its proximity to Hamas, the dominant faction in the Gaza Strip and politically aligned with the Brotherhood's theses, preventing the repair of diplomatic relations that had been severed following the Israeli attack on the humanitarian aid flotilla which, in May 2010, tried to circumvent the blockade imposed on the Gaza Strip, resulting in the death of several Turkish activists4.

What is more, its relations with the Iraqi government had been seriously damaged by agreements with the Iraqi Kurdistan Autonomous Region (KRG) for the supply of oil5 and by military operations against PKK6 sanctuaries in the north of the country after the breakdown of the negotiation process in the summer of 20157.

A minimally objective analysis of the evolution of Turkey’s relations with the Western world would not qualify them as a success story. On the European side, Turkey's accession to the EU, a major strategic objective of the Turkish government, had been de facto blocked by the impossibility of overcoming differences over controversies of existential importance to Turkey, such as its relations with Greece and the Cyprus conflict, both of which were further complicated by the discovery of vast amounts of energy resources in the eastern Mediterranean. The Syrian refugee crisis in 2015, the consequences of which posed a serious problem for both sides, not only prevented a rapprochement, but also added an extra layer of mistrust to relations. What is more, relations with Washington, never easy, but seriously deteriorated since 2003 when the Turkish parliament denied the use of its territory for the invasion of Iraq by US forces, had barely been restored and the US decision to rely on the Kurdish PYD/YPG8 in 2014 as a preferred ally in its anti-Da'esh operations in Syria did away with any possibility of establishing sincere dialogue between the two.

However, the policy of "zero problems with neighbours" did allow Turkish diplomacy to extend its influence into the post-Soviet space, the Caucasus and Central Asia, with some success. First, Turkey had been able to establish a strategic partnership level relationship with Ukraine, including close cooperation of its defence industries; and second, it had promoted the formation of a triangular cooperative partnership with Georgia and Azerbaijan, with whom it had quasi-twinning relations. However, despite attempts at rapprochement, its relations with Armenia remained non-existent. Nonetheless, with its sights set on the Turkic republics of Central Asia, in 2009 it promoted the founding of the Organisation of Turkic States, an intergovernmental cooperation body that currently includes Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkey and Uzbekistan. Inevitably, all these circumstances ended up negatively influencing its relations with Russia, with whom it shares a maritime border in the Black Sea and with whom it eventually clashed in Syria, especially after the shooting down of a Russian fighter jet that had invaded its airspace in November 2015.

Of course, not all the accumulated foreign policy failures can be directly attributable to Turkish diplomatic mistakes, with the deteriorating security situation in the region having much to do with it. The evolution of the terrorist phenomenon on its own territory and along its entire southern border particularly needs to be taken into account. Starting with Da'esh, which by mid-2014 had firmly established a foothold in northern Syria and Iraq and since 2015 had proven itself capable of carrying out deadly attacks in Turkey's major cities of Ankara and Istanbul9; and continuing with the PKK, which after the breakdown of the negotiation process in July 2015 had resumed its terrorist activity with repercussions in Iraq and northeastern Syria, where its affiliate the PYD/YPG, as mentioned above, had become the dominant faction thanks to US support.

In short, taken as a whole, Turkish foreign policy had proven incapable of achieving its objectives. A change of course was needed and in May 2016 President Erdoğan decided to sack his prime minister and intellectual father of the 'integrationist approach', Ahmet Davutoǧlu, who was blamed for the disaster.

Following President Erdoğan's public apology for shooting down the plane, Davutoĝlu's departure enabled the re-establishment of the deteriorated relations with Russia, a prior step towards a change in the orientation of its foreign policy which, through greater involvement of its military power, aimed to address the security problems that soft power had been unable to resolve (Fig. 2).

This paradigm shift received its final impetus just two months later, following the thwarted coup in July 2016, with the attitude of the various governments towards the attempted overthrow of President Erdoğan playing an important part. While Western partners and allies reacted slowly, coolly and, a posteriori, critically, with some even speculating that the coup had been orchestrated by Erdoğan himself10, the reaction from Moscow was immediate and unequivocal, offering Erdoğan not only unconditional political support to quell the rebellion but, as later reported in the press, military assistance too11. These events have been little appreciated in the West, but the support offered at that difficult time by President Putin was one of the most pivotal moments in Turkey's foreign relations in the more than five years since then. It was clear that despite the enormous differences between their respective strategic visions, it was essential to reach an understanding with Russia.

With their blessing, the Turkish armed forces were able to carry out a series of military operations in Syria that allowed it, in the first instance, to drive Daesh away from its territory but, above all, to interfere with Kurdish aspirations to establish a corridor linking PKK bases in northern Iraq to the Mediterranean via the PYD's domains in Syria and along its southern border12. Simultaneously, and in response to the evolving situation, it increased its naval presence in the Mediterranean area with the intention of avoiding faits accomplis and "marking territory", leaving no doubt whatsoever as to the strategic value it attached to this region and its natural resources. Its military intervention in Libya in 2019 to prevent the fall of the Libyan Government of National Accord (GNU) in Tripoli enabled it to secure a major exclusive economic zone (EEZ) delimitation agreement to bolster its case13.

All these actions have gone hand in hand with the expansion of its defence industry, with the joint aim of influencing its environment including, if necessary, regional rivals such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE, and making profitable an economic sector that it considers strategic.

However, by the end of 2020 and after four years of implementation, while the successes of these military interventions on the ground were evident, so were their adverse effects. At a geopolitical moment of renewed competition between major global powers14, the pursuit of an autonomous and realistic foreign policy was not without risk, requiring maintaining a delicate balance between Turkish interests and those of the other actors involved: on the one hand, Russia; and on the other the Western powers, especially the US and some EU countries such as France and Greece. And this had not been achieved.

Although understanding with Russia was initially boosted following the thwarted coup in July 2016, divergent objectives at the strategic level in the Syrian and Libyan conflicts eventually highlighted the limits of this cooperation. Their historically pragmatic but asymmetric bilateral relationship, in which Turkey is the weaker party, had hardly been altered. This was despite notable gestures such as the acquisition of the sophisticated Russian-made S-400 anti-aircraft system, a move that has proven highly counterproductive for the balance of relations with the United States which, considerably deteriorated already, reached one of the lowest points in recent decades15. So much so that Turkey has become the first NATO member to be subjected to US sanctions and expelled from the 5th generation F-35 fighter programme, an acquisition that is essential to renew its air force and maintain air superiority over its rivals in the region. Not even its military intervention in Syria to fight Daesh has managed to break US support for the PKK affiliate which, as mentioned above, is the main stumbling block in their relations.

While in terms of balance, the situation with the potential powers was far from satisfactory, their military action in the Mediterranean in support of their territorial claims has also exacerbated tensions with France, Greece and Cyprus, inevitably spilling over into their relations with the EU as a whole. And not only that. The militarisation of the problems in this region has resulted in the formation of a political association encompassing Egypt, France, Cyprus, Greece, Israel, Italy, Jordan and the Palestinian Authority, which clearly works against Turkey’s interests: the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF).

Nor was Turkey able to improve its strategic position in the Middle East. The conflicts in Syria and Libya deepened the polarisation around the HHMM mentioned above, consolidating the association of Arab nations (Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Egypt and the United Arab Emirates) with the common denominator of opposing Turkish interests in the area that spans from the Persian Gulf to Libya. The Century Agreement presented in January 2020 to the Palestinian Authority16 and the Abraham Accords of the summer of the same year were a serious setback for Turkey as a champion of the Palestinian cause, strengthening ties between the anti-Turkish Arab association and Israel, whose interests are also opposed to those of Turkey.

However, not everything was negative. With Ukraine and other countries of the post- Soviet space in the South Caucasus, Central Asia and Africa, where it has carried out a notable diplomatic expansion17, the balance was at least partially favourable. Nonetheless, the overall picture was worrying and the country was in a situation very close to international isolation. In short, and as Turkey's former ambassador to the US, Namik Tan, aptly put it, the country had been transformed from an 'island of stability' in the Middle East to a diplomatic 'island of solitude'18 (Fig. 3).

When Joe Biden won the US elections in November 2020, it was clear that foreign policy based on extensive use of hard power had reached its limits. And Biden's arrival did not bode well for Turkey. While President Trump had shown considerable tolerance towards Erdoğan during his term in office19, even trying to avoid the application of sanctions that the law provides for those who contract with embargoed Russian companies20, the new occupant of the White House had in the past been unfriendly to the Turkish president whom, in an interview with the New York Times in January 2017, he had called an'autocrat', explicitly stating the need to materialise his support for opposition leaders to 'stand up to and defeat Erdoğan'21.

The domestic outlook was not optimistic either. By now, the Turkish economy’s deterioration was difficult to disguise and in the eyes of analysts the situation was beginning to look worryingly similar to the vicious circle of inflation and depreciation22 of the Turkish Lira23 into which the country had been plunged in the late 1990s, and which had brought it to the point of disaster. The last thing that was needed was to hinder, let alone prevent, direct trade and investment relations from Western countries, most notably EU members with whom, from this point of view, Turkey is intrinsically linked (Fig. 3).

There were many open fronts both at home and abroad which, with the 2023 presidential elections in sight, had to be closed, meaning once again readjusting a foreign policy that had obviously reached its limits. A complex challenge which, at a geopolitical moment of renewed rivalry between great powers, required the reconciliation of sometimes contradictory objectives. On the one hand, the revitalisation of its economy required the recovery of its position as a strategic partner of the US and a reduction of tensions with the EU without breaking the hard-won "privileged" relations with Russia. And on the other hand, it was essential to secure the national interest by consolidating its advances in Syria, Libya, the Caucasus and the Mediterranean area.

Beginning with notably moderating the tone of its rhetoric, Turkey soon began a Middle Eastern rapprochement with the anti-Turkish bloc countries (Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Egypt and the UAE), which is already beginning to bear fruits24 25 26, although its relationship with the HHMM from Syria and Egypt, whom it welcomes on its territory, will need to be adjusted. Nothing beyond the reach of a realpolitik in tune with its most immediate national interests. Erdoğan's recent visit to Saudi Arabia confirms this trend27.

Improved relations with the Arab bloc are expected to contribute to easing tension in the Mediterranean area, for which understanding with Israel is essential. To this end, Turkey is seeking to exploit the advantages of its geographical position and gas infrastructure as a transit route for Israeli gas exports to Europe28, an option that has gained in value following the withdrawal of US support for the EASTMED Pipeline project29. This requires toning down rhetoric and moderating support for the Palestinian cause. Once again, it is to be hoped that the implementation of a realistic policy will help to align its objectives with its national interests30. At the same time, Turkey is trying to defuse tensions with neighbouring Greece, having revived old communication mechanisms that had fallen by the wayside in recent years31. Tension between the two, with historical underpinnings, remains high and sporadic incidents in Aegean and Mediterranean waters should be expected. However, a minimal détente, which cannot happen without goodwill on both sides, would allow Turkey to substantially improve its relations with the EU.

Further in this direction, Turkey has re-established talks with Armenia with the intention of normalising relations, for which the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict was a sine qua non condition. Azerbaijan's recovery of most of this territory at the end of 2020 has meant that one of the biggest hurdles to overcome has been removed, although the thorny issue of recognition of the so-called "Armenian genocide" remains to be resolved32. It is still too early to determine the extent to which the goal will be achieved, but given the influence of the Armenian diaspora in countries like the US and France, countries in which this community is especially numerous33, any improvement in their relations will, at least indirectly, contribute to improving Turkey's relations with these Western powers.

In this process of 'damage control', which was already developing successfully, two events with profound geopolitical consequences have enabled Turkey to establish itself as an indispensable regional power: the US withdrawal from Afghanistan and the war in Ukraine.

For Turkey, the first has been a magnificent opportunity to assert its capacity for dialogue with the Taliban regime, emerging together with Qatar as a key player in maintaining at least open lines of communication with Western powers and NATO. Its influence in Central Asia can also be of great use to the US if it wants to gain access to this region, Russia and China's backyard, which has hitherto remained out of its reach.

And regarding the second, the difficult balancing act that has allowed Turkey, not without taking considerable risks, to maintain relations with Ukraine and Russia simultaneously has begun to pay off and has allowed the country to position itself as the best possible mediator for a resolution of the conflict. The peace talks held in Antalya (11-13 March 2022) with the participation of the foreign ministers of both countries, the highest level talks to date34, and subsequently in Istanbul (29 March)35 are sound proof of this. This is all the more remarkable given that Turkey has not only not recognised Russia's annexation of Crimea in 2014, but is also the main supporter of the Tatar community on the peninsula, or what remains of it36, which has repeatedly irritated Russia.

Since the start of the armed conflict on 24 February, Turkey has made considerable efforts to maintain a degree of neutrality towards the two sides and, although politically closer to the Ukrainian government, has avoided excesses when referring to Russian actions. It is true that in the early stages Erdoğan was quick to criticise NATO's response and to qualify the West's reaction to Russian aggression as weak37. However, Turkey voted in favour of the UN General Assembly's condemnatory resolution on 2 March and, more recently, has closed its airspace to support flights to the Syrian stage of operations38. These are all gestures that place Turkey unequivocally close to Western views, which will hugely valuable depending on how the conflict evolves. At the same time, however, Turkey cannot ignore the fact that it is still dependent on Russia economically and militarily in areas of operations such as Syria and Libya. For this reason, it has sought to distance itself from other NATO allies by choosing not to adhere to the string of sanctions imposed on the Russian regime and by avoiding the closure of its airspace to Russian civilian aircraft.

Turkey has also been very careful to implement the Montreux Convention, which regulates the passage of warships through the Turkish Straits, the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles, to which Turkey is a guarantor. Its Article 19 requires preventing access to and from the Black Sea to warships of belligerent states in the event of war, in this case Russia and Ukraine39. The implementation of the Convention was expected to be problematic given that, among other considerations, if the conflict is prolonged the continuation of Russian operations in Syria will be severely hampered. However, in an attempt to compensate for the obvious prejudice caused to the Russian fleet, Turkey has gone beyond what is strictly required by the Convention and has also closed the straits to warships in general, thus preventing NATO warships’ access to the Black Sea. Neither issue has caused any problems so far, but it cannot be ruled out that should the war in Ukraine become 'frozen' for a prolonged period of time, this matter could become an additional source of friction between Russia and Turkey. And let us not forget that Turkey is a member of NATO.

Turkish foreign policy since the AKP came to power in 2002 has sought to make Turkey a regional power which, by regaining the power and prestige that the Ottoman Empire enjoyed in the past, is capable of extending its influence in the territories that once belonged to it. It is an objective that has remained unchanged over the years, despite the evolution of the geopolitical environment at both the global and regional level forcing an ongoing adaptation of its external action strategy to achieve it.

Policies based on the application of the supposed ascendancy of its Ottoman past, initially guided by an inclusive approach full of good intentions and employing soft power resources as a priority, has ended up clashing with the stubborn reality of geopolitics. The divergence of interests with its Western partners and allies and the different views on regional problems, especially those related to its own security, led the Turkish government to adopt an increasingly autonomous and independent foreign policy which, in an attempt to resolve its security needs that were not always shared, gave greater prominence to the use of military power. The problem with the implementation of this policy, which has in fact had some successes, is that it has exacerbated tensions both with its Western partners and allies and with regional rivals, encouraging the formation and consolidation of associations whose aims are against its interests, leading to diplomatic isolation. Thus, for example, the partnership between Greece, Cyprus, Egypt and Israel has been strengthened by the signing of the Abraham Accords, bringing the Arab powers of the Persian Gulf into the equation.

The situation was further complicated by the changeover of the US presidency at the beginning of 2021, which was expected to be hostile towards the Turkish regime, especially its president. With presidential elections in the offing in 2023 and an equally complicated domestic scenario of a deteriorating economy difficult to disguise, the Turkish government was forced to take measures to redress a very unfavourable and, above all, unsustainable situation in the long term.

Beginning with a noticeable moderation in the aggressive tone of its rhetoric, Turkey embarked on a foreign policy "damage control" campaign to smooth the rough edges and draw closer politically to all rival powers which, it must be acknowledged, has been successfully carried out. In these circumstances, recent developments in global geopolitics have contributed to this shift towards moderation. The US withdrawal from Afghanistan, a country in which Turkey wields considerable influence, and above all the war in Ukraine, have allowed Turkey to profit from a risky policy of balancing East and West, which in the past had caused many problems.

Indeed, the return of great power rivalry, while differing considerably from the Cold War period, once again gives Turkey a value similar to that which, as a country bordering the Soviet Union, it held during those years. To this effect, and despite considerable opposition from more than a few leaders in Washington and many European capitals, Turkey has been able to regain much of the political capital it had squandered in recent years. However, while the benefits of an undeniable proximity to the Western bloc have begun to show, Turkey remains dependent on its still powerful northern neighbour for key issues such as energy supplies, trade relations and support of its military operations in Syria and Libya. Turning its back on Russia is not a viable option and it is to be expected that Turkey will do its utmost to keep its mediation capacity intact.

Once again, Turkey moves in an unstable balance between Western powers and its geopolitical rivals. The good news is that whether or not it succeeds in achieving a lasting ceasefire in Ukraine, Turkey will have been able to demonstrate to the world that it remains an indispensable actor to be reckoned with. The bad news is that, the longer the conflict in Ukraine remains unsolved, the more likely will be that Turkey is forced to take side, risking its relations with Russia and compromising its balancing act. Only time will tell.

Felipe Sánchez Tapia

Colonel. IEEE Analyst

@sancheztapiaf

Referencias:

1 Sánchez Tapia, Felipe. Entre Oriente y Occidente: ¿Quo vadis, Turquía? IEEE Analysis paper 26/2019. https://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_analisis/2019/DIEEEA26_2019FELSAN_Turquia.pdf (accessed in May 2022).

2 DAVUTOĞLU, Ahmet. Turkey's Foreign Policy Vision: an Assessment of 2007. Insight Turkey Vol. 10/ No. 1/ 2008 p. 77-96.

3 The concepts of hard power and soft power were introduced by Joseph Nye in the 1990s (Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power, 1990). Hard power and soft power are generally translated into Spanish as ‘poder duro’ and ‘poder blando’, respectively. We consider the Spanish translations to be unsatisfactory, as they do not reflect the essence of the concept that the terms encompass.

4 "Israel kills at least 9 people by attacking humanitarian aid ships", El Mundo, 31 May 2010. Available at https://www.trtworld.com/mea/erdogan-urges-joint-effort-with-russia-to-solve-syria-crisis-161076 (accessed in April 2022).

5 Difficulties between the Iraqi government and the KRG over the sharing of hydrocarbon supply revenues date back to 2007, when the KRG passed its own law on the matter without the central government's input. RAK's contracts are not limited to Turkish companies, but this disrupted relations between them. See 'FACTBOX-Oil companies active in Iraqi Kurdistan', REUTERS, 5 January 2011. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/iraq-oil-kurdistan- idUSLDE70403M20110105 (accessed in April 2022).

6 Kurdistan Workers Party.

7 "Turkey's Erdogan: peace process with Kurdish militants impossible', REUTERS, 28 July 2015. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-turkey-kurds-idUSKCN0Q20UV20150728 (accessed in April 2022). 8 The PYD is the Syrian political party affiliated to the PKK and the YPG is its armed wing.

8 The PYD is the Syrian political party affiliated to the PKK and the YPG is its armed wing.

9 "A Timeline of ISIS Attacks in Turkey and Corresponding Court Cases", International Crisis Group, 29 June 2020. Available at https://www.crisisgroup.org/timeline-isis-attacks-turkey-and-corresponding-court-cases (accessed in April 2022).

10 "'No excuse' for Turkey to abandon rule of law: EU's Mogherini', REUTERS, 18 July 2016. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-turkey-security-eu-mogherini-idUSKCN0ZY0EZ (accessed in January 2022).

11 "Russia offered to help Turkey's Erdogan on night of failed coup - Kathimerini", Ahval News, 22 July 2019. Available at https://ahvalnews.com/july-15/russia-offered-help-turkeys-erdogan-night-failed-coup-kathimerini (accessed January 2022).

12 Euphrates Shield (2016), Olive Branch (2018) and Fountain of Peace (2019) operations. Furthermore, in direct cooperation with Russia within the framework of the Astana forum, Turkey deployed military forces to the northwestern enclave of Idlib in September 2018, where they remain today. This deployment allows it to exert some control over certain factions of the opposition to the Syrian regime and, above all, to prevent an undesirable flow of refugees into Turkish territory.

13 Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of the Republic of Turkey and the Government of National Accord State of Libya on delimitation of the maritime jurisdiction areas in the Mediterranean, 27 November 2019. Available at https://www.un.org/depts/los/LEGISLATIONANDTREATIES/PDFFILES/TREATIES/Turkey_11122019_%28HC%29_ MoU_Libya-Delimitation-areas-Mediterranean.pdf (accessed in April 2022).

14 NATIONAL SECURITY STRATEGY of the United States of America, December 2017. Available at https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf (accessed in May 2022) e INTERIM NATIONAL SECURITY STRATEGIC GUIDANCE, March 2021. Available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/NSC-1v2.pdf (accessed in May 2022).

15 Sánchez Tapia, Felipe. Turquía, entre el S-400 y la pared. IEEE Analysis Document 13/2022, 23 February 2022. Accessed at https://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_analisis/2022/DIEEEA13_2022_FELSAN_Turquia.pdf (accessed in April 2022).

16 “PEACE TO PROSPERITY: A Vision to Improve the Lives of the Palestinian and Israeli People', The White House, 28 January 2020. Available at https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Peace-to-Prosperity- 0120.pdf (accessed in April 2022).

17 Sánchez Tapia, Felipe, «Turcáfrica», poder virtuoso en acción. IEEE Analysis Document 29/2020, 23 September 2020. Available at http://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_analisis/2020/DIEEEA29_2020FELSAN_TurcAfrica.pdf (accessed in April 2022).

18 Tan, Namik. “Turkey’s road to diplomacy of loneliness”, Yetkin Report, 15 September 2020

19 “Trump Says Obama Treated Erdogan Unfairly on Patriot Missile”, BLOOMBERG, 29 June 2019. Available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-06-29/erdogan-says-no-setback-on-missile-system-deliveries-from- russia (accessed in April 2022).

20 Countering America's Adversaries through Sanctions Act.

21 Interview with Joe Biden, The New York Times, 17 January 2017. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/01/17/opinion/joe-biden-nytimes-interview.html (accessed in April 2022).

22 In January 2021 inflation was above 12% and trending upwards. By March 2022, it has reached 61% (Trading Economics at https://tradingeconomics.com/turkey/inflation-cpi ).

23 Over the course of 2020, the Turkish Lira had depreciated by 40% against the US dollar.

24 “Turkey: Exports to Saudi Arabia increase 25 percent in the first quarter of 2022", Middle East Eye, 5 April 2022. Available at https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/turkey-saudi-arabia-exports-increase-first-quarter (accessed in April 2022).

25 "Turkey, Egypt inch toward long-awaited normalisation', Arab News, 13 April 2022. Available in https://www.arabnews.com/node/2062676 (accessed in April 2022).

26 “Turkey's exports to UAE surge over 50% following Erdoğan's visit”, DAILY SABAH, 22 March 2022. Available at

https://www.dailysabah.com/business/economy/turkeys-exports-to-uae-surge-over-50-following-erdogans-visit (accessed in April 2022).

27 “Erdogan visits Saudi Arabia hoping for new era in ties”, REUTERS, 29 April 2022. Available at https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/turkeys-erdogan-travel-saudi-arabia-thursday-2022-04-28/

28 "Israel-Turkey gas pipeline discussed as European alternative to Russian energy”, REUTERS, 29 March 2022. Available at https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/israel-turkey-gas-pipeline-an-option-russia-wary-europe- sources-2022-03-29/ (accessed in April 2022).

29 "US withdraws support from EastMed gas pipeline project”, Agencia ANADOLU, 11 January 2022. Available at https://www.aa.com.tr/en/world/us-withdraws-support-from-eastmed-gas-pipeline-project/2470881 (accessed in April 2022).

30 "Turkish-Israeli rapprochement alarms Hamas: experts”, The New Arab, 22 March 2022. Available at https://english.alaraby.co.uk/news/turkish-israeli-rapprochement-alarms-hamas-experts (accessed in April 2022).

31 “Turkey, Greece agree to improve ties amid Ukraine conflict”, REUTERS, 14 March 2022. Available at Turkey, Greece agree to improve ties amid Ukraine conflict | Reuters (accessed in April 2022).

32 "Turkey and Armenia close to normalization”, DAILY SABAH, 12 April 2022. Available at https://www.dailysabah.com/opinion/columns/turkey-and-armenia-close-to-normalization (accessed in April 2022).

33 1,600,000 in the US and 650,000 in France - OFFICE OF THE HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR DIASPORA AFFAIRS.

34 "Lavrov and Kuleba meet in Turkey to discuss Ukraine conflict", EuroEFE, 10 March 2022. Available at https://euroefe.euractiv.es/section/exteriores-y-defensa/news/lavrov-y-kuleba-se-reunen-en-turquia-para-hablar-del- conflicto-de-ucrania/ (accessed in April 2022).

35 “New round of Russia-Ukraine peace talks starts in Istanbul”, Agencia ANADOLU, 29 March 2022. Available at https://www.aa.com.tr/en/politics/new-round-of-russia-ukraine-peace-talks-starts-in-istanbul/2548768 (accessed in April 022).

36 Ukraine's ethnically Turkic Muslim Tatar minority has traditionally opposed the incorporation of Crimea into the Russian Federation. Population figures are difficult to define accurately, but it is estimated that, prior to the Russian annexation, between 10% and 15% of the population was of Tatar origin. Many of them left Crimea after the annexation. For more information see "Crimean Tatars: Eight Years of Anything but Marginal Resistance", EjilTalk, blog of the European Journal of International Law, 25 March 2022. Available at https://www.ejiltalk.org/crimean-tatars-eight-years- of-anything-but-marginal-resistance/ (accessed in April 2022).

37 "Erdogan says NATO, Western reaction to Russian attack not decisive", REUTERS, 25 February 2022. Available at https://www.reuters.com/world/erdogan-says-nato-western-reaction-russian-attack-not-decisive-2022-02-25/

38 “Turkey closes airspace to Russian military aircraft to Syria: FM Çavuşoğlu", DAILY SABAH, 23 April 2022. Available at https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/diplomacy/turkey-closes-airspace-to-russian-military-aircraft-to-syria- fm-cavusoglu (accessed in April 2022).

39 Compendium of International Treaties registered with the Secretariat of the League of Nations for the year 1936. Available in the United Nations Treaty Collection, https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/LON/Volume%20173/v173.pdf , p. 213 onwards. (accessed in April 2022)