The Crazy Train

Unlike England or France, which specialised in beheading kings, Spain preferred to get into the habit of sending them into exile. However, where Spaniards win by a landslide is in assassinating presidents. There have been five since the second half of the 19th century: General Prim (1870), Cánovas del Castillo (1897), Canalejas (1912), Dato (1921) and Admiral Carrero Blanco (1973).

The second of these, the conservative leader, architect of the Restoration, the Constitution of 1875 and six times head of government, Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, was shot three times on 8 August 1897 by the Italian anarchist Michele Angiolillo. The latter argued that Cánovas had died in the name of revenge, to honour the anarchists arrested and executed in Barcelona months earlier, as a result of the attack on the Corpus Christi procession.

The assassination took place in one of the most elegant spas of the time, Santa Águeda, in Guipúzcoa. Having been the scene of the assassination of the most important Spanish political figure of the late 19th century, the place was converted, barely a year later, into a psychiatric hospital, which in the popular terminology of the time was better known by the word that had become a curse: madhouse. Patients from Zaragoza and Valladolid, whose hospitals for those who without frills or circumlocutions were called mad, were full to overflowing, were transferred to it in a bizarre journey.

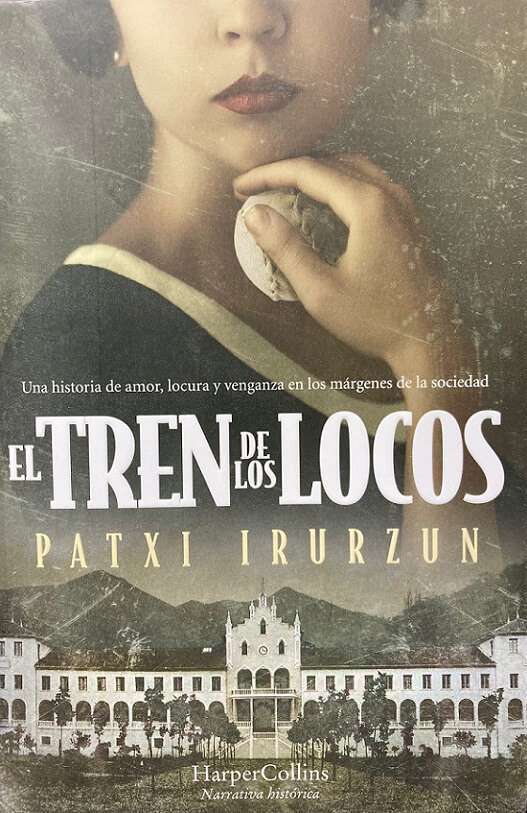

Such is the great event, the backdrop and the pretext with which the Navarrese writer Patxi Irurzun (Pamplona, 1969) builds the plot of his new novel The Crazy Train (El tren de los locos) (Ed. Harper Collins, 350 pages). A new historical and adventure story to add to his first two brilliant incursions into a genre in which he is already an authority: 'Los dueños del viento' and 'Diez mil heridas'.

Such is the great event, the backdrop and the pretext with which the Navarrese writer Patxi Irurzun (Pamplona, 1969) builds the plot of his new novel The Crazy Train (El tren de los locos) (Ed. Harper Collins, 350 pages). A new historical and adventure story to add to his first two brilliant incursions into a genre in which he is already an authority: 'Los dueños del viento' and 'Diez mil heridas'.

Through the eyes of Maurizia, a worker at the spa, Irurzun recreates the years that made it famous and turned it into a summer meeting point for the most influential men - women still played little or no role in Spain and Europe - in the capital and, in short, in the country. These were the joyous moments of a belle époque in anticipation of what was soon to be the disaster of '98, the loss of Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines, and the final closure of the Spanish Empire.

There are memorable phrases, such as the one in which the author winks at John Lennon: "Waiters can clap their hands, the rest of you can clap your jewels". There are also numerous traces of the sardonic and apparently simple humour of the Basque countryside, in contrast to the refined and elegant atmosphere of the San Sebastián of those years.

A year before the assassination of Cánovas, three shots are also fired at Xalbador, Maurizia's boyfriend, a young pelotari who, after recovering from his wounds, sets out in search of his mysterious attacker, whom he pursues through several cities. In Paris, Xalbador will become part of the Apaches, the dangerous youth gangs that terrorise the French capital; he will frequent the Barcelona underworld at a time when the Catalan capital is falling prey to violent clashes between bosses and workers; He will be a photographer of the dead and a pornographer in Madrid, a genuine Spaniard in short, capable of going up to the palaces and down to the huts, of blaspheming without malice out of ancestral custom, and of cheating to survive, but always maintaining the dignity of his origins, tinged by the everlasting drive for appearance over reality.