The flight of multinationals in Argentina is accentuating

Multinationals are leaving not for the present, but for the future of the nation.

Numerous examples show that not only productive foreign direct investment capital is leaving, but also local investors, at the same time as the value of Argentine companies is being sold off. The outflow of productive investment from the country is a direct consequence of frequent macroeconomic crises, permanent regulatory uncertainty and the lack of credibility and extreme discretionality of economic policy.

With the country mired in a deep economic recession, there is no sign that the situation will improve in the short term, so a climate of pessimism reigns among the business community. Any business that is profitable in Argentina must translate its profits into dollars. These profits are often minimal, making the Argentinean market increasingly unattractive.

"In the specific case of the dairy sector, the main problem is uncertainty, which means that very few people dare to continue investing. Argentina has all the natural and climatic conditions to produce food at lower costs than other competing countries, but unfortunately in the last fifteen years we did not know how to take advantage of the tailwind we had. We need a more favourable business climate, in which the private sector plays a key role. Rather than talking about distributing wealth, we should be looking at how to generate it," said Ercole Felippa, president of the Cordoba dairy Manfrey and head of the Dairy Industry Centre.

Argentina is one of the largest economies in Latin America, with a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of approximately 450 billion dollars. It has abundant natural resources in energy and agriculture. Within its territory of 2.8 million square kilometres, the country has extraordinarily fertile agricultural land, significant reserves of gas and lithium, and enormous potential in renewable energies. In addition, Argentina is a leader in food production, with large-scale industries in the agriculture and beef sectors. It also has great opportunities in some manufacturing sub-sectors and in the innovative high-tech services sector.

But all these strengths, which could make the country a regional (or even global) power, are untapped. The historical volatility of economic growth has impeded the country's development. The COVID-19 pandemic and social isolation as a way to combat it aggravated the situation. According to data provided by the World Bank, urban poverty in Argentina remains high at 42.9% of the population in the second half of 2020, with 10.5% indigence and child poverty (children under 14) at 57.7%.

The report 'COVID-19 in Argentina: socio-economic and environmental impact' presented by members of the United Nations reveals that the informal economy is exploding. In 2019, the rate of people who were not officially registered was 35.9%, and according to the report it could rise by 3 to 5 points in the coming months.

In the World Bank's recent Doing Business report, which aims to identify the best countries in which to invest, Argentina obtained dismal results. The country presided over by Alberto Fernández tops the ranking of countries with the highest tax burden, not only in the region, but in the world. The president's tax initiatives, such as the corporate income tax, represent a step backwards compared to the reductions adopted by Mauricio Macri during his term in office. Of the 190 countries analysed by the ranking, Argentina is ranked 126th, nine places lower than in 2019, and 170th in terms of its tax system.

The Argentine government has been characterised by increasing taxes in the midst of the worst economic and social crisis since 2001, the COVID-19 pandemic, demonstrating a concern for reducing the fiscal deficit, although at the cost of practically provoking "pymecide" by charging higher taxes to businesses and single-taxpayers who are forced to close or reduce their turnover. These measures increase the tax burden on the middle class and SMEs, the real engine of employment and prosperity in the country.

These initiatives, in a country that has been mired in an abysmal economic recession for many years, include: the suspension of the reduction of gross income, the failure to update the tax base for personal property tax, the solidarity contribution of wealth and the increase in corporate income tax scales.

The tax burden is increasing because updating mechanisms such as adjusting balance sheets for inflation are not allowed. "The result is that companies are having a greater tax burden, as their balance sheets are practically not adjusted for inflation, which means that the payment of profits exceeds the 35% that the law states, since the costs of the companies are at historical cost and their sales at present value," said economist Salvador di Stefano.

If tax scales are not adjusted for inflation or are adjusted below inflation, individuals and firms move into higher and higher tax brackets as their nominal income rises, even if their real income remains the same. The taxpayer ends up bearing an increased tax burden and, with it, the resulting loss of disposable income due to inflation. This strangles SMEs and discourages entrepreneurship and foreign investment.

Meanwhile, the state grants small benefits to the population that partially compensate for what they otherwise charge while undermining productive activity. This is the case, for example, with income tax. It was initially perceived as beneficial for the population, since it allows for a temporary reduction for individuals whose income is below the new minimum taxable income of $150,000 per month.

According to this initiative, the Federal Administration of Public Revenues will return to taxpayers the difference retroactively from January, but in instalments that will be liquefied by inflation, so the return to citizens will be minimal. The owner of an SME that owns premises will be excluded from this benefit because he or she is a personal property taxpayer. But they will also see their tax burden rise for owning an SME, as the government has raised the corporate income tax rates to compensate for the supposed loss of revenue.

In short, the state does not lose revenue, but rather increases the tax burden on companies, discouraging production, job creation and investment. Furthermore, the benefit granted to individuals below the threshold of the new income tax is practically non-existent.

The trend is clear: in 2015, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner left power with a fiscal pressure of 31.5% of GDP according to official data from the Ministry of Economy. This was the highest percentage recorded to date. During Mauricio Macri's four years in office, this indicator fell to 28.7% of GDP. Alberto Fernández, in little more than a year, undoes practically all the fall of previous years and has, for now, brought the fiscal pressure up to 30.5%.

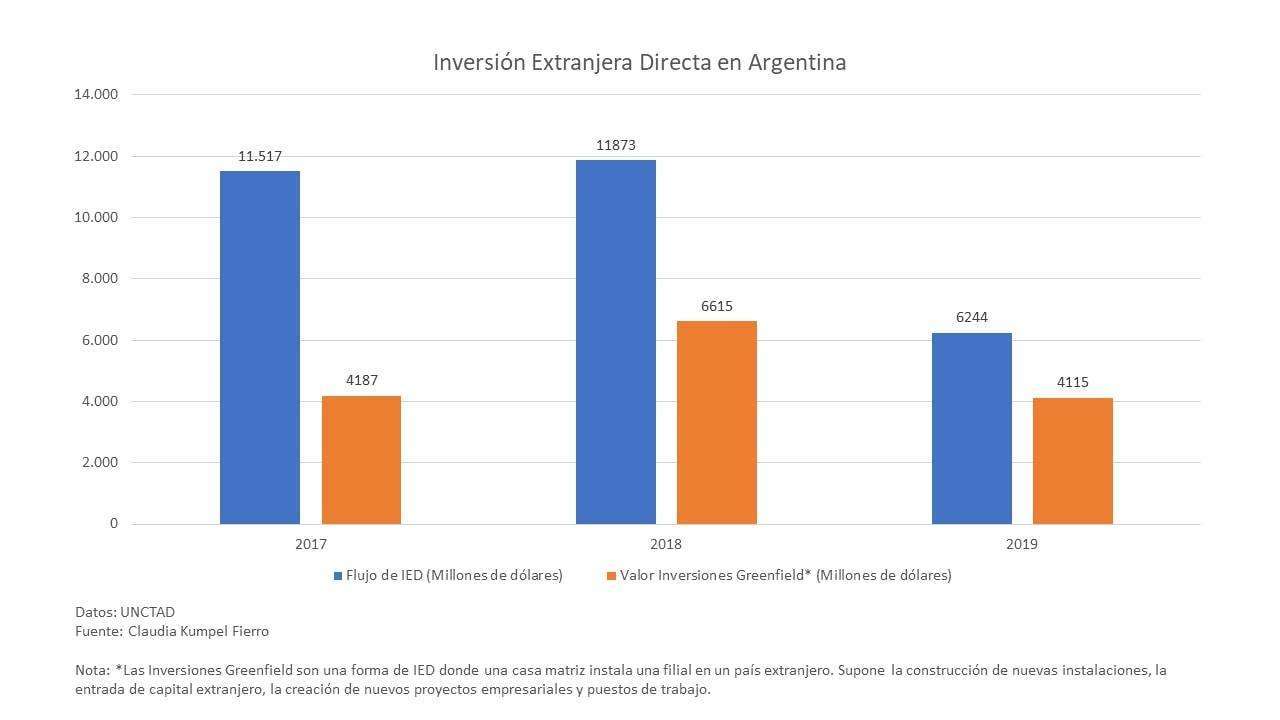

Foreign direct investment (FDI) in Argentina went into decline in 2019, with the arrival of the new government and when such measures began to be adopted. From 2018 to 2019, FDI fell by almost half, as well as Greenfield investments, the most beneficial for the development of the country's economy. According to the World Bank, in 2020, flows to Argentina fell by 47%, as the COVID-19 crisis exacerbated pre-existing trends in the country.

All this is causing Argentina's assets to devalue enormously. The massive withdrawal of multinationals generates a climate of unease among the companies that remain and, together with the measures adopted by the government and the economic crisis resulting from the pandemic, more and more companies are deciding to leave the country. As assets are so devalued, the investments seen in the country are generally opportunistic. They are not motivated by the will to make a long-term bet, but by the ridiculous price of the assets and the possible immediate profits they can offer to the buyer. This type of investment has nothing to do with the kind of "genuine" investment that contributes to stimulating the Argentine economy.

The exodus of multinationals has to do not only with internal factors, but also with regional factors: many companies are leaving not only Argentina, but South America as a whole, in search of more profitable destinations, such as the Asian market. Regional disinvestment is the case of companies such as Eli Lilly, which last week announced the closure of its direct operations in the country and the transfer of the management of its brands - such as Prozac and Cialis - to the national laboratory Raffo. The company's regional withdrawal also includes exiting Chile, Peru, Ecuador and Central American countries. This change will take effect from 1 September.

The same happened with companies such as Glovo, which sold its business in Argentina to PedidosYa in 2020 and also left Brazil and Chile, as well as Nike, which plans to continue operating through a licensee in the country. These withdrawals are part of a long list of international companies leaving the Argentine market. According to a report by consultancy First Capital Group, since the beginning of 2020 there have been at least 18 operations where a multinational group decided to close or sell its local operation.

The main exit deals included the companies: Walmart, Falabella, Latam Argentina, Air New Zealand, Emirates, Qatar Airways, Norwegian, Axalta, PPG, Pierre Fabré, Under Armour, Gerresheimer, Asics and Brighstar. Likewise, the buyers who appear on the market when a multinational puts the "for sale" sign on its local subsidiary are Argentine businessmen. This was the case of Walmart, acquired by the ex-deputy Francisco de Narváez, and of Brightstar, in the hands of Mirgor.

The US multinational electronics manufacturer Brightstar announced that it was selling its operations in the country to a local competitor for the modest sum of 82 Argentinean pesos or $1 (or, strictly speaking, $0.49 at the free exchange rate). It had 450 employees, healthy accounts and contracts to manufacture some 2 million mobile phones a year for Asian companies LG and Samsung, but the companies are not leaving for the present, but for the future of the nation. Foreign companies are seeking to "escape" from Argentina at any cost, even taking millions of dollars in losses, as in the case of Brightstar.

The Chilean firm, Latam, suffered during the last decade under the governments of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, currently vice-president of the Peronist government of Alberto Fernández, which through various measures restricted its operations to favour the flag carrier. In June the company announced that 1,700 people were to be laid off. It had 16 per cent of the domestic market, with 12 destinations, and had been operating in the country for 15 years.

The fact that solvent companies are willing to "run away" from Argentina at a loss of millions of dollars is a clear indicator of the business climate; the country's conditions are not conducive to foreign direct investment and foreign companies do not dare to invest in their market. Moreover, despite the fact that Argentinean assets have low dollar prices, the market is no longer attractive or profitable for foreign companies.

Among the reasons cited by companies for leaving the country, apart from those related to the pandemic, are the complicated ways of doing business, the presence of powerful trade unions, state interventionism, anti-commercial policies, changing politics, and price and currency control. If the government does not take measures to encourage investment, this situation is not likely to improve in the short term - quite the contrary.