Iran's role in the Middle East (I)

The recent events in the Middle East and the open confrontation between the United States and Iran, fought on Iraqi soil, have highlighted a reality that until now, although it was known, had not received the attention it deserves, showing the reality of the complicated "game" of interests in that region and making it clear once again that elements that some people today are trying to proclaim as novel, framing them in concepts such as "the hybrid war" which, by the way, is beginning to be abandoned to talk about "conflicts in the grey zone", are not so much. And not only that, but actors who might be thought to be less advanced have been using them for decades, sometimes as true masters of them.

It's interesting to stop for a moment, look back and think. Because only from the knowledge of past events can we understand where we are and, along the way, perhaps there are those who manage to separate the dust from the chaff and recover a more objective vision.

Since the revolution of the Ayatollahs in 1979 and the proclamation of the Islamic Republic of Iran, this country, in its efforts to establish itself as a regional power and to occupy a prominent place in the predominantly Sunni Muslim world, has incited and promoted the creation of groups throughout the Middle East that have acted as "proxies", both politically and militarily, to influence regional and international policy in favour of its interests. These groups, in most cases, have led to militias that have acquired sufficient relevance to be considered in some cases as non-state actors, but with almost the same capacity for influence as the states in the area themselves.

This way of acting has become much more relevant with the invasion of Iraq and the fall of Saddam Hussein's regime in 2003. The collapse of the Iraqi state and the situation of chaos after the invasion presented a more than favourable scenario for Iran, as it meant the disappearance of one of its main competitors in the region.

In the last years it has taken again strength due to the conflicts in Syria, Libya and again Iraq in its fight against the Daesh, becoming the main tool of the Iranian regime to advance in the achievement of its regional objectives.

Traditionally, the West in general and especially since the attacks of 9/11, has directed its concern towards Sunni jihadist groups such as Al Qaeda and the Daesh, with the exception of Hezbollah, whose presence and activity in Lebanon have been a cause of constant concern and attention.

Numerous conflicts have suffered from the intervention of these Iranian "proxies", and the Iranian government's efforts to recruit volunteers to feed the ranks of its militias, not always with the same success, have not ceased since the late 1970s. Not surprisingly, this attitude has not gone unnoticed by Iran's regional competitors, from Israel to Saudi Arabia to Abu Dhabi. The result is none other than the situation that presents itself today, the result of a worrying trend that has gradually increased and materialized the risk of entering a vicious circle of actions and responses in which violent sectarianism has become a fundamental element in the hands of various states in their attempt to achieve their geopolitical goals and ambitions.

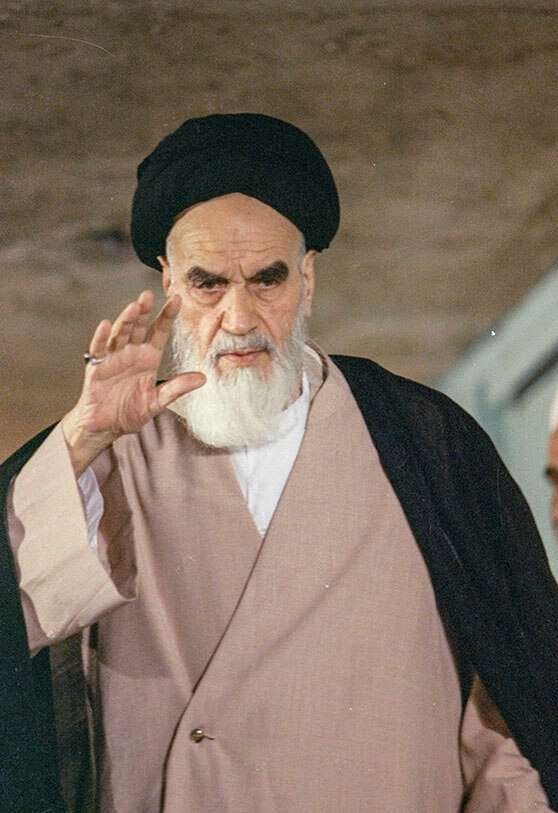

The origin of this "modus operandi" can be dated back to the early years of the existence of the Islamic Republic of Iran and its founder, Ayatollah Khomeini, who developed the facet of sectarianism in Tehran's quest to achieve real geopolitical influence in the area. And the way he started this path was to incite the Shiite communities in Iraq to rise up against the Sunni-type Ba'ath party and its leader and strongman of the country, Saddam Hussein. All this, despite the fact that for more than a decade the new Iranian ayatollah had enjoyed Iraqi hospitality with the condescension of Saddam Hussein in his exile in the city of Najaf.

Arab nationalism or pan-Arabism has always been characterised by an intrinsic tendency to reject the Shiite current, and this offered the perfect opportunity for the new Iranian leader. As early as 1971, Khomeini set out his ideas for an "Islamic government", which he put into a book. In his notion, the idea prevailed that it should be transnational, with all the Shiite communities as its main members.

A defining characteristic of Khomeini's vision is that religion and politics are two inseparable realities, something that contradicts the Shiite tradition that always advised maintaining a healthy distance between political and religious power.

Even so, this radical new interpretation of religion and the intrusion of religious postulates into politics had direct consequences for the country. In fact, Joemeini's incitement to rise up against the power of Saddam Hussein was one of the key factors that led to the invasion of the Persian country by Iraq in 1980.

Only two years after the fall of the Shah, the new Iranian regime set up the Office for Islamic Liberation Movements, under the umbrella of the Republican Guard and with the mission of exporting the Iranian model of revolution. And in 1982, with Tehran's help, the anti-Saddam Badr militias in Iraq and Hezbollah in Lebanon emerged, both made up of Shiite Islamists imbued with the Khomeini inspired doctrine of ending all political resistance. Today, both groups are the most effective and powerful pro-Iranian Shiite proxies.

During that decade, elements inspired by Iran's radical policies emerged, including sporadic violence in Bahrain, Kuwait, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia.

Importantly, and sometimes deliberately ignored, much of what is happening in the Middle East is within the framework of the struggle within the Islamic world to maintain hegemony. Since the separation of Islam into its two main currents, the followers of one and the other have struggled to impose themselves on the other. And it is that struggle that lies at the heart of today's confrontations. Of course, seasoned with another series of not minor conditions, such as the energy factor, the economic factor, the presence of an actor like Israel and the intervention of the western powers.

For this reason, the strategy followed by the Shiites and supported by the Islamic Republic of Iran is very similar to that followed by similar groups of the opposite current, such as the Muslim Brothers.

Both groups initially aim to delegitimize the established power by all possible means, transferring to the population that it does not respond to their demands and needs, creating a certain feeling of "orphanhood" that leads them to seek a reference. Once this has been achieved, the seed of insurrection is sown and the conditions for an armed uprising to take power are created, thus imposing an Islamic government governed by "sharia" or Islamic law.

This formula was first used successfully by the Shiite majority in Iran, providing them with a powerful state with significant resources that led them to become the base of operations for the revolution of that religious current. The leaders of the new Islamic Republic set about redefining the Shi'ite Islamic world and seeking ways to export their vision to communities that followed the same faith beyond the country's borders.

This determination is clearly demonstrated by the fact that the 1979 Constitution enshrines the Republic's ideological commitment to mobilize the so-called "mustzafeen", oppressed Muslims, against what Tehran called unjust rulers. This task concerns Muslims generally, without making any distinction between Shiites and Sunnis. But as Afshon Ostovar states, "critics of Iran tend to see the country's performance since 1979 as expansionist and transnational behaviour to implement a pro-Iranian Shiite policy". But looking at the evolution of the latter in more detail, one can certainly see sectarian elements that have a great influence on Iran's strategic calculations, without following a single pattern as critics of the regime point out.

There are key moments in which Tehran's role has ignored what were a priori its sectarian preferences. A case in point is the civil war in Lebanon in the early 1980s. During the conflict, Iran supported the Fatah movement led by Yasser Arafat, which was Sunni in nature and opposed to the Lebanese Shiite group Amal. At that time, Tehran prioritized Arafat's belligerent position against Israel over Amal's position focused exclusively on the interests of Lebanon's Shiite community. This, along with many others, highlights how Iran, despite everything, has always applied what is known as "realpolitik". Beyond its agenda and ideology, it always acts to suit the situation for the greater benefit. This is what could be called a sectarianism subject to the practical interests of the country's geopolitical strategy.

Pro-Iranian militias operating in the Middle East region are a constant threat to the stability of the area, as well as to the possibility of achieving stable and peaceful governments. From a strategic point of view, Iran's somewhat novel way of acting, using proxies to achieve its political and military objectives, has proved to be a difficult problem to approach, understand and counter in a holistic manner.

For this reason, it is very important to know the origin of this "modus operandi" and its roots in order to establish a theoretical model that responds to how Tehran uses these resources, what the dynamics of these groups are and what their real interests are in the region, far beyond the usual clichés.

Iran has been concerned with weaving a dense network of relations with these non-state actors to the point of using them as an extension of the Islamic Republic's own means and resources within the dynamics of the new conflicts, whether they are called hybrids or conflicts in the grey zone. And it does so in a way that encourages certain clashes, provokes others or lowers the tension in some of the existing ones according to its own interests.

While the so-called "War on Terrorism" is in some ways beginning to disappear from the discourse and the security ambitions and aspirations of states are again taking a leading role, Iran's activities and its particular conduct in the Middle East are perpetuated as a challenge and a source of problems.

The groups created by the Iranian regime or those with which it has established close ties because of shared interests and ideology with Tehran, wage wars or carry out political activities in line with Iran's interests, and in return they obtain military and financial support and, on many occasions, advice and political support in the international arena.

Through this dense network of proxies, Iran has been able to create a regional "security" network with tentacles in practically all the countries of the region, despite a clear position in opposition to the Iranian interests of these states.

This particular way of acting presents an unusual complexity and a challenge to all those who have to design strategies to counteract it.

The key questions are two: "What are Iran's real objectives in the region? And how will it act to achieve them?"

They both seem obvious. What is no longer obvious is the answer to neither. There are many factors that interact in Iran's decision-making process, sometimes even contradictory to each other, and many overlaps making it difficult to understand.

But the two main drivers of the Iranian strategy can be identified, making a first basic analysis, which are none other than the maintenance of its security and the expansion of its ideological objectives.

On the one hand, the establishment and employment of its related militias, as well as with the development of its military power, seeks to increase its security through deterrence, trying to bring it not only to its potential regional enemies but to any external actor that may try to interfere in its domestic affairs, even though these sometimes affect third parties, as is the case of the development of its nuclear program. This is largely based on the threat posed by such proxies as an active combat force capable of acting in conditions very different from those of a conventional military conflict. On the other hand, we have the permanent attempt, since the creation of the Islamic Republic, to export its model of revolution and the Shiite ideology that forms the basis of its theocratic form of government.

This brief look at the past and this brief glimpse of the way Iran acts may help to understand in part what is happening during the last months in Iraq, since it highlights the relevant historical ties of the Iranian Shiite Islamists with their co-religionists in Iraq, as well as the way these groups act under the leadership of the Islamic Republic, showing how deep is the religious and political influence of Tehran in the current Iraqi reality. Perhaps it will shed some light on the origin of the events of last January.

Bibliografía

- Emmet Hollingshead “Iran’s New Interventionism: Reconceptualizing Proxy Warfare in the Post-Arab Spring Middle East” Macalester College, ehollin1@macalester.edu (2018)

- Alex Vatanka. “Iran’s use of shi‘i militant proxies ideological and practical expediency versus uncertain sustainability” Policy Paper (2018)

- Holly Dagres & Barbara Slavin. “How Iran Will Cope with US Sanctions” (2018)