NATO and the ‘Southern Flank’. Balance and future prospects in light of the Madrid Summit 2022

This document is a copy of the original which has been published by the Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies at the following link.

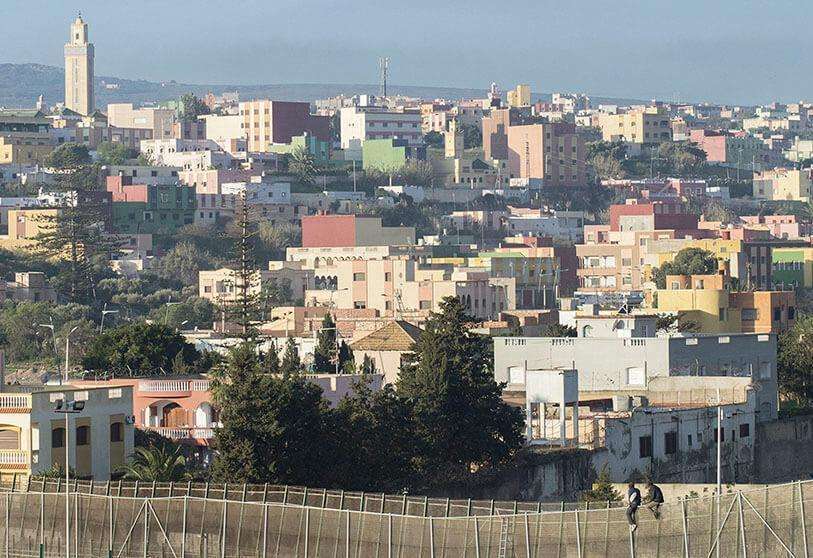

NATO is secure only when all its borders are secure, and today the southern flank of the transatlantic region needs much more attention. Neighbouring countries, in particular in North Africa and the Sahel, face significant interconnected security, demographic, economic and political challenges, aggravated by the impact of climate change, weak institutions, health emergencies and food insecurity. This unstable situation provides fertile ground for the proliferation of non-state organizations and armed groups, including terrorist organizations. It also allows destabilizing and coercive interference from strategic competitors like Russia or China. Strengthening NATO's southern flank is therefore crucial for the Atlantic Alliance given the strong correlations between conflict, fragility and instability in Africa and the Middle East, and the security of the Alliance and the Allies. The Madrid summit in June 2022, with the approval of the new Strategic Concept, is an excellent opportunity to increase the Alliance's level of commitment to 360° security, also in the Southern Flank.

The term NATO's ‘Southern Flank’ has geopolitical as well as historical connotations. In the early 1950s, NATO introduced the term into its security strategy in order to integrate southern European countries such as Greece, Italy and Turkey into the Western defence system. It was retained in the post-Cold War era but with a new meaning as it now encompassed the southern Mediterranean basin, with North Africa and the Middle East as the main areas of interest due to their proximity to Euro-Atlantic borders.

The demise of the formidable adversary that had been the Soviet Union enabled NATO to take a broader and more ambitious approach to its security strategy by extending it to neighbouring countries to the east and south through the idea of ‘partnership’. A broad concept that made it possible to complement the classic deterrence and defence of previous decades with the new notions of cooperation and security demanded by the new times. The Alliance's radius of action gradually expanded to include regions outside the Washington Treaty area, bringing the southern flank into the Euro-Atlantic security field of vision for the first time.

The 1991 Strategic Concept stated that in a context where ‘in Central Europe, the risk of surprise attack has been substantially reduced[...]. The stability and peace of the countries on the southern periphery of Europe are important for the security of the Alliance’. 1. This recognised that Europe's security was intimately linked to security and stability in the Mediterranean, an approach that was echoed years later in the 1999 Strategic Concept. This was in response to the sensitivities of some southern European Atlantic partners who, like Spain, argued that ‘conflict spill-over from fragile or failing states, instability caused by and stemming from terrorism and transnational terrorist groups, as well as all forms of illegal trafficking, cyber threats, and also chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) threats, and challenges in maritime security’ generated security threats in the Mediterranean and North African regions that had a direct impact on the Alliance's security2.

NATO's Mediterranean Dialogue (MD) emerged in 1994 as an initiative that brought together seven non-member countries from the Mediterranean region with the overall aim ‘to contribute to regional security and stability, achieve better mutual understanding and dispel any misconceptions about NATO in participating countries’3. A first group of countries joined the Dialogue in 1995, comprising Egypt, Israel, Mauritania, Morocco and Tunisia, followed by Jordan in 1997 and Algeria in 2000.

The Dialogue was restrictive in its level of geographical ambition, leaving out a significant number of countries in the Middle East, the entire Sahel and Libya, and relying on political dialogue between NATO and Mediterranean partners that would allow for a shared vision of security challenges. A community of security interests could thus be created on both sides of the Mediterranean Sea in which all participants would feel comfortable. Mediterranean Partners were offered the possibility of doing so either bilaterally (NATO+1 format) or multilaterally (NATO+7 format).

At the same time, the dialogue was complemented by practical, two-way cooperation that would help improve understanding and eliminate suspicions, and in which both sides would benefit from each other's experience and expertise in areas that NATO and Mediterranean partners understood to be shared threats. These areas mainly concerned countering violent extremism, critical energy infrastructure protection, missile defence and cyber security.

In the following years, NATO saw the Dialogue as a fundamental part of the process of approaching security in the Mediterranean. This was in line with the 1999 NATO Strategic Concept, which called for the establishment of a framework of trust and confidence between the Alliance and its partners, while promoting transparency and cooperation in the region by reinforcing other international efforts. NATO's aim was to enhance the political, civilian and military aspects of the Dialogue in a way that would lead to ever- closer cooperation to enhance a shared response to security problems in the Mediterranean. But the resources employed were insufficient and the results soon proved unsatisfactory.

NATO did not play a leading role in the political events that, like the 1991 Gulf War, were to shake the southern Mediterranean region in the following years. Nor was it involved, even in a collateral way, in the Middle East peace process, considered for decades the most distorting element of regional security. In doing so, NATO missed an excellent opportunity to become a decisive actor bringing added value to an area that was to prove increasingly important in terms of Euro-Atlantic security and where other regional organisations such as the Arab League, the Organisation of African Unity (which became the African Union in 2003), or the European Union did not have the intention or the capacity to intervene at the time4.

The causes were manifold, but easily understandable. From the outset, the Dialogue was underfunded and the resources NATO gave to the programme were in no way comparable to the enormous effort made over the years with the countries of Eastern Europe. NATO offered them, as part of the much more ambitious programme that became known as the Partnership for Peace, the ultimate goal of full Alliance membership, provided they met certain criteria. This was a path forbidden to the Mediterranean partners on the more political than legal grounds of the geographical limits defined in Article VI of the Washington Treaty.

The result was a lack of interest by Mediterranean countries in finding formulas for regional integration or cooperation that would bring the countries of the southern basin closer to the European democratic socio-political model, as well as a much less powerful integrating effect of the Mediterranean Dialogue than that achieved by NATO with Eastern countries.

In addition to this discrimination between Eastern and Southern partners in terms of how NATO's treated them, the Mediterranean Dialogue suffered from the outset from a number of additional shortcomings. The first was having to compete with a wide range of regional initiatives, which increases confusion and ‘dialogue fatigue’. While NATO was aware of this, it complacently assumed that this situation was in any case preferable to the Alliance's strategic neglect of its southern dimension in previous decades.

The second shortcoming concerned the heterogeneity of its members and the interests they defended (Southern European versus Northern European countries, North African versus Middle Eastern, Algerian versus Moroccan, Israeli versus Arab, etc.) and thus very different, and often conflicting, visions of Mediterranean security issues. This resulted in a lower level of ambition when it came to identifying common goals, interests and values with Europeans, which would allow for the design of successful cooperation strategies.

Of particular concern was the inclusion of Israel in the Dialogue, a country that was always seen by Arab partners as a disruptive element, given the complex situation of the Middle East peace process. No resolution for the Arab-Israeli conflict, coupled with Arab countries' disinclination to cooperate with Israel, tainted the Dialogue from its inception to the point where it allowed for only low-profile activities, but no decisive steps towards a shared vision of regional security.

Nor can it be said that the lack of regional organisations on the south shore that would allow all of them to speak with one voice helped the dynamics of the Dialogue. The result was a dysfunctional situation, with a Euro-Atlantic north shore consisting of 30 powerful and wealthy countries that, although with different views, spoke with a single voice modulated by the rule of consensus, compared to seven interlocutors on the south shore who spoke individually, so that the dialogue was conducted on unequal terms. Thus, the last word always belonged to NATO, which paid for the Dialogue's activities.

This was a major weakness for the Mediterranean partners and made them feel relegated to a subordinate position, which did not help to improve their confidence in NATO. The result was a certain mistrust felt by these Mediterranean partners of the Alliance's intentions, exacerbated by NATO's role in theatres such as Libya and Afghanistan.

At the turn of the century, NATO was an organisation that ‘does not see itself as an adversary of any country’. To the classic tasks of security, consultation, deterrence and defence, NATO had added crisis management and partnership, missions that were very much oriented towards out-of-area action. This intended to turn NATO into what US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright called a "force for peace from the Middle East to Central Africa"5.

The November 2002 Atlantic Council summit in Prague recognised the need to change the Alliance into an effective instrument of global military power and projection. This resulted in a profound transformative impulse that was particularly visible in three critical areas: capacity building, action outside the Euro-Atlantic area, and counter-terrorism.

The inclusion of out-of-area action and the fight against terrorism, together with the 9/11 attacks, gave more importance to the southern flank, which seemed destined to play a preferential role in Euro-Atlantic security in the 21st century. Afghanistan apparently confirmed the trend when NATO decided to take over the UN-mandated Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (ISAF). This mission was considered by NATO Secretary General Jaap de Hoop to be ‘NATO's top priority’.

The intervention in Afghanistan had the collateral effect of producing a radical change in NATO's relations with the Gulf states, to the extent that the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) became extensively involved in these efforts. Thus, Bahrain deployed members of its special forces to Afghanistan; Kuwait provided parking and overflight permits for all forces in the operation; Qatar offered the allies the use of its Al Udeid air base; and the United Arab Emirates provided specialised troops and the Al Minhad Air Base as a support centre.

The Allies understood the importance of working with Arabian Peninsula nations, as reflected at the NATO summit in Istanbul in June 2004, which ushered in a new era of Allied engagement in the Middle East6. At the Istanbul summit, the Allies formally invited Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) to form alliances with NATO under what became known as the Istanbul Cooperation Initiative (ICI). The aim was to seize the historic opportunity to complement the Mediterranean Dialogue, so that the ICI ‘will be developed in a spirit of joint ownership with the countries involved. Continued consultation and active participation will be essential to its success’.

However, only four of the six GCC countries became formal members (Kuwait in 2004 and Bahrain, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates in 2005), while Oman and Saudi Arabia refrained from joining, remaining merely as guests and only willing to cooperate with NATO on a case-by-case basis. Other regional powers such as Iraq, Syria and Iran were not even invited, so the initiative was limited from the outset.

Perhaps its greatest achievement was the creation of what Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg called "NATO's new home in the Gulf"; a ‘NATO-ICI Regional Centre’ located in Kuwait whose mission, approved at the 2012 NATO summit in Chicago, was to ‘strengthen political dialogue and practical cooperation in the ICI’ and ‘help us better understand common security challenges, and discuss how to address them together’.

At the beginning of the last decade, NATO adopted its 2010 Strategic Concept ‘Active Engagement, Modern Defence’ at the Lisbon Summit and envisaged a Euro-Atlantic area at peace, and a strategic context in which the threat of a conventional attack on NATO territory was low, allowing NATO to concentrate on other scenarios. The proliferation of nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction associated with the use of ballistic missiles, along with terrorism, border instability, cyber-attacks and energy security became the new threats to NATO. The centre of gravity of continental security thus moved away from central Europe and increasingly to the periphery. Military priority gradually shifted towards strengthening the defence of the southern flank, considered the most vulnerable on the continent7.

Collective defence was nevertheless maintained as a fundamental pillar of Euro-Atlantic security, but NATO prioritised crisis management and cooperative security in its 2010 Strategic Concept, which came to be seen as essential core Alliance tasks and were intended to be implemented outside the Euro-Atlantic area and preferably on the southern flank. Crisis management aimed to employ the political and military tools necessary to prevent crises in these peripheral scenarios from escalating into conflicts, to stop ongoing conflicts that affect Alliance security, and to help consolidate stability in post-conflict situations. In doing so, NATO believed it was contributing to Euro-Atlantic security.

Cooperative security, on the other hand, was aimed at stability in peripheral countries to which NATO offered the possibility of becoming partners on issues such as arms control, non-proliferation and disarmament. The door to Alliance membership was kept open to all European democracies that met NATO's political and military standards, but not to countries in the southern region.

The 2010 Strategic Concept presented, however, two blind spots that would soon blow the envisaged ‘strategic peace’ out of the water. These were the Arab spring of 2011 and increased tension with Russia as a result of events in Ukraine in 2014. NATO failed to anticipate them in a serious miscalculation of risk and maintained its preference for crisis management in Afghanistan, following a course of action that would last until the beginning of the current decade.

The so-called 'Arab Springs' of 2011 had a major impact on the stability of the 'southern flank', and showed that the 2010 Strategic Concept was insufficient to prevent, let alone manage, such crises. The collapse of decades-long regimes in Egypt, Libya and Tunisia and destabilising unrest in the others forced the Alliance to reconsider its role in the region, and to look for options that would allow these countries to navigate smoothly through their difficult political processes.

NATO's 2011 'Unified Protector' operation in Libya, executed through a 'Coalition of the Willing' generated within NATO but not involving the Alliance as such, starkly demonstrated the political and operational limits of NATO's willingness to intervene in the southern region. Libya showed that the Allied operational strategy of combining air power, the deployment of some special forces and, above all, the use of indigenous forces served to seize but not stabilise power.

The Western intervention in Libya, considered by NATO Secretary General Rasmussen of Denmark to be ‘a template for future NATO missions’ 8 demonstrated, on the contrary, that without control on the ground and the creation of stable political structures beyond the tribes, successful crisis management was not possible in the theatres of operations in the southern flank. This required a long-term commitment to rebuilding the country that neither the Alliance nor the Allies were willing to make.

From a strictly military point of view, Libya demonstrated how relatively simple it was to intervene with air assets and without deploying troops in physically accessible scenarios where action could be taken either from the sea or from local bases in allied countries, and how complicated it was to access the internal theatres of operations, given that the greater the distance at which it was necessary to operate, the more the potential of the response was degraded. This is a lesson that NATO learned in Libya and applied in the Sahel when it refused to intervene in Mali in 2013, leaving the responsibility to external actors such as the French ‘Serval’ operation, or MINUSMA forces.

Libya also revealed differing sensitivities among Allies regarding NATO's approach to military interventions on the southern flank. Turkey's initial indecision over which side to take in Libya, Germany's refusal to endorse Security Council Resolution 1973 with the withdrawal of its support for the NATO mission —including its AWACS crews, essential for allied aircraft command and control— and Poland's harsh criticism of the Allied intervention as oil-motivated, highlighted how little appetite the Allies had for intervention in southern flank theatres of operations where their vital interests were not at stake. Not surprisingly, prestigious magazine The Economist described this view of crisis management operations as ‘a worrying tendency for member states to take an à la carte attitude to their responsibilities to the Alliance’9.

If the Arab revolutions were more of a cosmetic than a real shake-up in NATO's strategy, the same was not true of Russia's intervention in Ukraine in March 2014, an event that came as a surprise to the Alliance despite the precedent of Georgia in 2008. By the time NATO wanted to react, the Crimean peninsula had been occupied unopposed and the east of the country was in an advanced process of secession. Thereafter, Russia's containment in the east shaped NATO's preferences, which took the form of a ‘compensation strategy’ to exploit the advantage, both in quantity and quality, of NATO's conventional forces over Russia's10. The need to address the urgent security problem of Russian interventionism in Eastern Europe meant that the Alliance's southern dimension was relegated to the background.

NATO thus recovered a renewed preference for Article 5 missions of deterrence and collective defence, to the detriment of the crisis management that had dominated Allied interventions in the first decade of this century. However, NATO was aware that the situation in Iraq, Syria, or Libya, and the terrorist threat that was spreading in the Middle East and North Africa and beginning to take on worrying dimensions in the Sahel, required stabilisation in the broader Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.

Thus, the Alliance defence ministers' summit in June 2015 adopted a political declaration affirming the need to provide a 360-degree vision in the face of challenges and threats, based on the principle that ‘security is indivisible’11. At the 2016 Warsaw Summit a year later, NATO introduced the concept of ‘projecting stability’ understood as a combination of the crisis management and cooperative security missions set out in the 2010 Strategic Concept and aimed at addressing what NATO called ‘pervasive instability’12 on the southern flank. It proposed to shape the strategic environment of neighbouring regions by making them more secure and stable, which would ultimately be of strategic benefit to the Alliance13.

But this concept, more political than anything else, abandoned any pretence of transforming the countries in these regions into democratic states and was content to achieve a certain consensus among Allies on the need to ensure their stability, albeit with few practical aspirations. The southern flank was thus relegated to the slender east and NATO prioritised cooperative security over other tasks. This resulted in the ‘Resolute Support’ mission to train, advise and assist local forces in Afghanistan —following the December 2014 disbandment of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF)— as well as the limited ‘Inherent Resolve’ mission to train the Iraqi Army as part of the international coalition to fight Daesh, a mission that was to begin in 2018.

NATO's level of ambition in the south was drastically reduced, translating in the operational field into Article 5 Operation ‘Sea Guardian’, launched at the Warsaw Summit in July 2016, which was merely an adaptation of the previous counter-terrorism mission 'Active Endeavour' in the Mediterranean that had been in place since 2002. It was a maritime security operation that extended the counter-terrorism mission into the field of ‘maritime security building and situational awareness’, without NATO agreeing to play a role in European security concerns such as the fight against illegal immigration and people smuggling networks in the Mediterranean Sea. In this regard, NATO preferred to keep a low profile or, in the words of NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, to indicate that there are no military solutions to the migration crisis14, and that NATO is only committed to mitigating the situation on an ad hoc basis.

In Africa, it was terrorism ‘in all its forms and in all its manifestations’15 that topped NATO's list of priorities. Allied leaders agreed to strengthen political dialogue and practical cooperation with Mediterranean Dialogue partners in a two-way approach combining ‘their interests and ours, in the conviction that the relationship is mutually beneficial’16. The aim was to build stable institutions and stronger security and defence capabilities, enabling greater interoperability to combat the threat posed by terrorism.

NATO chose Tunisia, considered an ‘exception’ in the democratic development of North African political processes, as a testing ground for the new concept of projecting stability through cooperation. In this way, and on the basis of the Mediterranean Dialogue, the country entered in 2014 into an Individual Partnership and Cooperation Programme (IPCP) aimed at strengthening its capacity to combat terrorism and improve security along its borders. The programme for an enhanced bilateral partnership with NATO, heralded as a major achievement by NATO Secretary General Stoltenberg at the July 2016 Warsaw summit, was to be based on the establishment of an intelligence fusion centre located in Tunisia. However, expectations were not met as the Tunisians rejected counter-terrorism cooperation that they found overly intrusive17.

The conclusion drawn by the Alliance was that any security understanding with southern countries should be based on programmes that are less ambitious and more appropriate to partners' needs. In this context, NATO began work on designing tailored ad-hoc Defence Capability Development (DCD) packages, a demand-driven initiative tailored on a case-by-case basis to the needs of recipient nations. This initiative had been launched at the Allied Summit in Wales in September 2014 and aimed to help partners improve their defence and security capabilities and resilience through various types of support, ranging from strategic advice on defence and security sector reform and institutional development, the development of local forces through education and training, to advice and assistance in specialised areas such as logistics or cyber defence18.

But perhaps the most significant measure taken by NATO with the southern flank in mind was the inauguration in 2017, under the leadership of Allied Joint Force Command Naples, of a strategically directed ‘Hub’ to the South, a decision taken at the same time as the Alliance officially joined the Global Coalition against Da'esh. The Naples Hub was to be an element of ‘contact, consultation and coordination’19 in responding to conflicts arising in the southern region. As Secretary General Stoltenberg said, "this will help us to coordinate information on crisis countries such as Libya and Iraq, and help us address terrorism and other challenges stemming from the region"20.

However, things are more complicated. Beyond North Africa and the Middle East, the geographical mandate of the Naples Hub is unclear, i.e. whether and to what extent the Hub should also cover sub-Saharan Africa. Nor is its relationship defined with existing NATO regional partnerships, such as the Mediterranean Dialogue, which should be given special attention. The Alliance's official narrative does not offer much clarity on these points, but it seems logical to think that NATO should build on the cooperative realities put in place decades ago before dissipating efforts and resources on other projects. Added to this is the natural distrust of southern countries, especially African, to collaborate with a centre that they identify as a body for intelligence gathering rather than cooperation among equals.

The Madrid Summit in June 2022 is a milestone in NATO's vision of its role in the world, as it embraces the need for the Atlantic Alliance to play a greater role as an international security provider. NATO proposes that partners adopt a more global vision that takes into account the significant changes in the world since 2014 and, in particular, relations with Russia and the growing competition with China, which represent direct challenges for NATO and its members21.

In a security environment in which NATO prioritises territorial defence against a Russia considered in the Madrid Strategic Concept as an enemy and the need to address the systemic challenge posed by China, there is not much scope for the South and particularly for Africa whose responsibility seems to be dumped on the European Union as it seeks to become a ‘Global Actor’22. The document adopted by the EU on its ‘Strategic Compass’ in March 2022 seems to favour this division of tasks as the EU approaches security in a complementary way to NATO, which remains the basis of collective defence for its members23.

This European vision is shared by the Atlantic Alliance, which sees the two organisations as playing complementary, coherent and mutually reinforcing roles through cooperation24. But pursuing military cooperation initiatives will require Europeans to increase defence spending and develop capabilities that reinforce those of the Alliance, avoiding unnecessary duplication.

NATO's current emphasis on conventional military power to deal with competing major powers also makes it difficult to imagine large-scale crisis prevention and management operations in the southern periphery, as was the case in the Afghanistan mission, unless they have ‘the potential to affect Allied security’25 . More realistic is to envisage small military interventions on the southern flank, preferably on an ad hoc counter-terrorism basis, and to carry them out jointly with regional partners who express interest in contributing to them.

This vision has been reinforced by the new Madrid Strategic Concept in which ‘Terrorism, in all its forms and manifestations, is the most direct asymmetric threat to the security of our citizens and to international peace and prosperity’26. Counter-terrorism remains central to the Alliance's collective defence and is an integral part of its 360-degree deterrence and defence approach. Reassuringly, NATO reinforced in Madrid its commitment to counter, deter, defend and respond to threats and challenges posed by terrorist groups, based on ‘a combination of prevention, protection and denial measures’.

At the same time, NATO can be expected to expand cooperative security tasks by strengthening the military capabilities of its regional partners. This work is enhanced by Russia's worrying expansion of influence in the Sahel and its willingness, in the context of the war in Ukraine, to cause security problems for NATO in the region by fomenting growing hostility among local populations to what they see as European neo- colonialism27.

In this regard, the Sahel countries, hitherto outside the allied focus, require special attention. Russian presence, coupled with the expanding threat from terrorist groups that have found a safe haven in those countries, should encourage NATO's interest in greater and more constructive cooperation among allies and with regional partners to limit the influence of actors that are having such a damaging effect on the Alliance's stabilisation efforts. This is recognised in the NATO Foreign Ministers' report of late 2020 which concluded that ‘the deteriorating security situation in the Sahel and terrorist threats destabilising several nations in the region have the potential to affect transatlantic security’28.

NATO needs to play a relevant role as a security provider to avoid this, increasing its cooperation with other regional and international actors, in particular the European Union and the African Union, while avoiding duplication and without overburdening the limited capacities of local structures. It is about defining a division of labour that should be guided by the comparative advantages each brings to the table and with the objective of achieving the greatest possible added value in terms of regional stability, for NATO and for regional partners. As the final communiqué of the June 2021 summit rightly states, the Alliance needs to enhance ‘our long-standing engagement in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region’ and ‘build stronger security and defence institutions and capacities, promote interoperability, and help to counter terrorism’29.

This means that, in the midst of the war in Ukraine, security issues in Eastern Europe vis- à-vis a Russia that NATO now sees as its main threat, as well as adapting to an era dominated by strategic rivalry between great powers, will mark the Alliance's priorities for the coming years. But also that a NATO whose centre of gravity has shifted northwards with the addition of Sweden and Finland needs to incorporate the southern flank into its range of priorities if it is to become a full-fledged security provider. The new Strategic Concept should thus be understood as a unique opportunity to increase the level of engagement in 360° cooperative security, also on the southern flank.

In short, the Atlantic Alliance's role in the south is as indispensable as it is politically and operationally complex. The stakes for NATO are high and the consequences for Euro- Atlantic security are grave if NATO loses this battle. The debate is open within the Alliance and in member countries, albeit still in its early stages. We can only hope that the impetus provided by the Madrid Summit will serve to translate this awareness of 360-degree security problems into a greater commitment to a southern flank where physical spaces abound, such as the Sahel, which today remain uncontrolled.

Ignacio Fuente Cobo, DEM Artillery Colonel, IEEE Lead Analyst

References:

1 NATO. «NATO - Official text: The Alliance’s New Strategic Concept (1991), 07-Nov.-1991», Paragraph 7. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_23847.htm

2 NATO. «NATO - Topic: Mediterranean Dialogue». https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_52927.htm

3 Ibídem.

4 PROFAZIO, Humberto. «NATO’s limited leeway in North Africa», ISPI. 5 de julio de 2018, https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/natos-limited-leeway-north-africa-20926

5 «Madeleine ALBRIGHT quoted in Royal United Services Institute», Newsbrief, Vol. 18:4. April 1998, p. 26.

6 WEBB, Amanda. «The Istanbul Cooperation Initiative at 15», NATO Review. 16 December 2019,

https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2019/12/16/the-istanbul-cooperation-initiative-at-15/index.htm

7 SIMON, Luis. «Understanding US Retrenchment in Europe», Survival. International Institute for Strategic Affairs,

April-May 2015, pp. 162-165

8 WESTERVELT. «NATO's Intervention in Libya: A New Model?», NPR. 2011.

http://www.npr.org/2011/09/12/140292920/natos-intervention-in-libya-a-new-mode

9 «NATO after Libya, A troubling victory», The Economist. 3 September 2011. http://www.economist.com/node/21528248

10 PIFER, Steven. «NATO´s Response Must be Conventional, not Nuclear», Survival, vol. 57, n.º 2. IISS, April/May

2015, p. 121.

11 NATO. «Secretary General calls for NATO to make training a core task for the Alliance in the fight against extremism». 7 de abril de 2016. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_129756.htm

12 TARDY, Thierry. «NATO’s Sub-strategic Role in the Middle East and North Africa», GMF. February 11, 2022. https://www.gmfus.org/news/natos-sub-strategic-role-middle-east-and-north-africa

13 DÍAZ-PLAJA, Rubén. «Projecting Stability: an agenda for action», NATO Review. 13 March 2018.

14 CADALANU, Giampaolo y STOLTENBERG, Jens. «Libia, la NATO pronta ad aiutare l’Italia», La Repubblica. 23 June 2018.

15 «Brussels Summit Communiqué Issued by the Heads of State and Government participating in the meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Brussels 14 June 2021». https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_185000.htm

16 COLOMINA, Javier. «La Alianza y su aproximación 360º a la seguridad» en Cuadernos de Estrategia 211. Instituto

Español de Estudios Estratégicos (IEEE), 2022, p. 92.

17 PROFAZIO, Umberto. «Tunisia’s reluctant partnership with NATO», International Institute for Strategic Studies. 6 April 2018. https://www.iiss.org/blogs/analysis/2018/04/tunisia-reluctant-partnership-nato

18 NATO. «Defence and Related Security Capacity Building Initiative». 9 de junio de 2022. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_132756.htm

19 NATO. «What is the NATO Hub for the South?». 9 August 2019. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_168383.htm#:~:text=It%20is%20crucial%20for%20the%20Alliance,leads%

20to%20stability%20for%20the%20Alliance.&text=It%20is%20crucial%20for,stability%20for%20the%20Alliance.&tex t=crucial%20for%20the%20Alliance,leads%20to%20stability%20for

20 «NATO Hub in Naples». Europe Diplomatic. 15 de febrero de 2017.

21 GHANEM-YAZBECK, Dalia y KUTZNETSOV, Vasily. «Moscow’s Maghreb Moment». Diwan-Carnegie Middle East Centre, 13 June 2018.

22 EU External Action Service. «The EU as a global actor». 13/3/2022. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/eu-global- actor_en

23 European Council. «A Strategic Compass for a stronger EU security and defence in the next decade». 23 March 2022.

24 NATO 2022. Strategic Concept, p. 10. https://www.nato.int/strategic-concept/index.html

25 Ibídem, p. 9.

26 Ibídem, p. 4.

27 KHADY, Ndèye LO, & BOUBOUTOU-POOS, Rose-Marie. «Françafrique: quelle est l'histoire du "sentiment anti- français" en Afrique et pourquoi il resurgit aujourd'hui?», BBC News. 28 mai 2021. https://www.bbc.com/afrique/region-56971100

28 COLOMINA, Javier. ‘La Alianza y su aproximación 360º a la seguridad’ in Strategy Paper 211, Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies (IEEE), 2022, p.94.

29 NATO. «Brussels Summit Communiqué». 14 June 2021. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_185000.htm