War and «bibliocide»: destruction and censorship of collections in Russia and Ukraine

This document is a copy of the original which has been published by the Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies at the following link.

When there is a deliberate destruction of books and the censorship of authors for ideological, racial or religious reasons by groups or States, it is pertinent to speak of

«bibliocide». In most of these cases, the physical removal of the works is followed by that of the people. Russia and Ukraine have been waging an intense cultural war, which since 2014 has been becoming real, whose greatest exponents have been the manipulation of historical memory in both countries and the control of editorial production to adapt it to their political and national discourses. This entails the censorship of Ukrainian or Russian works and authors, depending on the country we are referring to and not caring at all about the universal literary prestige or the time in which they wrote. War also involves the physical destruction of libraries and collections as a form of retaliation against the enemy or for the destructive effects of military actions on the ground.

When listening to or reading news about the persecution of authors or the deliberate destruction of books around the world, the images of the public burnings in Germany in May 1933 often come to mind. Even today, those multitudinous covens are a symbol of the censorship of the written word, which is why contemplating those scenes, which were not lacking in ceremonies from other, darker times, still sends shivers down one’s spine1. The destruction of books and the censorship of authors and works is not unique to Germany under the Third Reich. Throughout history there have been attacks on the writings of those who were portrayed as different, enemies or corrupters of the official truth. This is symbolised as much in the Nazi burnings as in the destruction of the thousand-year-old library of Alexandria by the Muslims in 640. Neither is the period from the end of the 20th century to where we are now in the 21st a stranger to these paper catastrophes2. We only need to recall the recent cases of the destruction of documentary heritage in Iraq during the war-torn period of 2003-2011, and the danger posed to the mythical library of Timbuktu, with more than 700,000 unique manuscripts, by the arrival of Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb in 20123.

Why are books attacked? British librarian Richard Ovenden offers a simple explanation. The written document, whether in paper or electronic format, is a guarantor of knowledge, the transmission of ideas and the memory of a given society. Therefore, it is also the target of individuals, groups and states who believe in the need to expunge it, manipulate it or force an alternative discourse to take hold in society4.

The book is a tool of information and knowledge whose reach is still very relevant today. The COVID-19 pandemic served to increase the time spent reading globally. Although dark clouds have been hanging over the publishing sector, the global book industry was estimated to be worth $119 billion by 2020, and the number of readers had increased by a significant 35% since 20195.

The destruction of books affects the cultural history of societies, but even more dangerously these acts are often the first warning sign of what is yet to come in simmering conflicts. Let us recall the quote from the German poet Heinrich Heine (1797-1856) in his drama Almanzor: "Where books are burned, people are burned too”.

The current conflict in Ukraine, following the Russian invasion in February 2022, has seen thousands of works destroyed or removed from the shelves of bookshops and libraries. This irreparable loss of documentary heritage is part of the even greater loss of cultural and artistic heritage in Ukraine6.

Publishing production and library holdings in the post-Soviet space were poor, first and foremost because of the lack of financial means, but also because of the previous strict censorship of works. Professor Tax Choldin explains that for Russian and other Eastern European libraries, exchange with Western centres was the only way to access books not in the inherited Soviet-era catalogue7.

Since 1991, the year of Ukraine's independence, the book situation has been improving, with more resources allocated to the publishing industry. At that time, the situation between Russia and Ukraine in the cultural sphere was one of mutual respect and protection of each country's national peculiarities. Thus, the Russian Federal Law on Libraries of 1994 recognised that library users had the right to both books in the Russian language and works in other languages recognised by countries formerly part of the USSR8. In Ukraine, the 1997 Law on Books included a commitment in Article 3 to "publish books in Russian to meet the cultural needs of the Russian population in Ukraine"9.

However, in the late 1990s a nationalist view of historiographical and literary discourse emerged, with authors portrayed either as part of a Russian or a Ukrainian essence, but not both. Already in 1999, the Russian government went to huge efforts to commemorate the bicentenary of the birth of the poet Alexander Pushkin (1799-1837), of Ukrainian origin but considered one of the founders of Russian culture and literature10.

In 2009, a bitter cultural dispute broke out between the Russian and Ukrainian authorities during the events of another bicentenary, in this case that of the birth of Nikolai Gogol (1809-1852), a native of Sorochintsy in present-day Ukraine. Was he a Russian or a Ukrainian writer? Other cultural and national appropriation disputes occurred with respect to great writers such as Anton Chekhov (1860-1904), Taras Shevchenko (1814-1861) and Mikhail Bulgakov (1891-1940), all born in Ukrainian localities, then part of the Russian Tsarist Empire or the later USSR11.

National projects underpinned by the narrative of historical memory accentuated the cultural dispute between Russia and Ukraine. First, the Holodomor, a term referring to the great Ukrainian famine of 1932-1933, is still the subject of historiographical debate. In 1998, then Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma named the fourth Saturday in November as the National Day of Remembrance for the Victims of the Holodomor, in response to a formal protest from Russia, which felt accused by Ukrainians of holding it responsible for the millions of deaths. The Security Service of Ukraine, not a cultural body, published a list of those allegedly responsible for the famine, including their names and surnames. The people on the list were of Russian origin and, in addition, most of them were Jewish. Protests from Russia and the Jewish Committee of Ukraine went unheeded12.

More controversial was the discourse on Ukrainian collaboration with the Nazi invaders during World War II, especially the ultra-nationalist Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) of Stepan Bandera (1909-1959). Ukrainian history books would disseminate that it was ethnic Ukrainians, and not others, who stood up to the Germans and then to the Soviet regime, now equated with Russian in general. In the readings of two generations of Ukrainian schoolchildren, the struggle for Ukrainian independence was presented as heroic and sacrificial, while the secular cultural relationship with Russia was silenced, as were the atrocities committed against other minorities, such as Poles and Jews, whose ancestral culture in Ukraine was practically wiped from memory13.

For its part, in February 2013 the Russian Ministry of Education reacted by publishing textbooks presenting a national history that moulded its own memory. Regarding the historiographical discourse on World War II, known in Russia as the Great Patriotic War, it would be argued that the then USSR, also accepted in Russia as synonymous with Russian power, went to war with Germany in 1941. A sacrificial and victorious war, but henceforth the German-Soviet Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 would be omitted, as would the Soviet occupation of the Baltic and parts of Poland, Romania and Finland between 1939-194014.

More specifically with regard to Ukraine, it was reported that during the German campaign in World War II, the Nazis destroyed millions of Russian books in Kiev and then set fire to the Kiev library. In total, the Germans were estimated to have destroyed 96 million Russian-language works in their military campaign in the USSR. The theoretical link between Nazism and collaborationist Ukrainian nationalism would be easy to trace15.

The publishing output in Ukraine and Russia seen from these very opposing national historiographical positions was exported via foreign texts and on subjects which, in principle, were outside the scope of both Russian and Ukrainian interest. One example is English-language works, translated and reinterpreted differently depending on whether they were intended for the Russian or Ukrainian publishing market, as demonstrated by Professor Natalia Olshanskaya in a study on the reception of US journalistic texts from the 2003 Iraq War16.

At the beginning of the Maidan revolt against the government of Viktor Yanukovych in November 2013, the destruction of books began in Ukraine. In Lvov, dozens of Soviet- era Russian-language books were destroyed by young Ukrainian nationalists, while in Sevastopol, pro-Russians burned boxes full of Ukrainian-language books from libraries and schools across the city. They had been symbolically piled up at the foot of the monument to Tsarina Catherine the Great. Other public burnings took place in Simferopol, also in Crimea, and in Kharkov Reuters images showed pro-Russian activists breaking into a cultural centre and burning several books on small bonfires17. The Maidan Uprising undoubtedly saw an acceleration in the expurgation and removal of works in Ukraine, crystallised in public burnings and destructions across the country by both pro- Yanukovych and non-pro-Yanukovych supporters during the first months of 2014.

The National Parliamentary Library in Kiev, heir to the one that had been burned down by the Germans in 1943, was the epicentre of the confrontations. The International Red Cross set up an emergency care centre there and Maidan activists joined with librarians to defend the integrity of the library and its holdings, while dozens of works in the collection, categorised as Russian or Soviet, disappeared18.

On 26 January 2014, activists also established the Ukrainian House in Kiev, a cultural institution that included a library destroyed by government troops. After the final victory of the revolt, this library was reopened with no Russian authors or those considered pro- Russian19.

Later in 2014, with the embers of the uprising still smouldering, the new Ukrainian cultural authorities began to censor literature they believed defended separatism and Russian disinformation. One of the first cases of this censorship was the successful detective novels written by the Georgian-born Russian writer Boris Akunin, because they were set in Tsarist Russia, even though he was highly critical of the Putin government's policies in the region20.

Also in 2014, Ukraine started implementing the project "Libraries and the electoral process: educating librarians and voters about their constitutional rights". This was an educational awareness programme to help citizens aged 18 and over to "exercise their right to vote more effectively", using libraries and books as a platform. The project was fully funded by the US Embassy in Kiev, according to the Ukrainian Library Association21.

Following the events of the Maidan Uprising and the annexation of Crimea in February 2014, Russia began to turn its attention to its Ukrainian-related publishing and literary industry. An unofficial purge of authors and works whose discourse was considered contrary to the Russian national interest was initiated.

In 2015, a court in the Oryol region sentenced Ukrainian-born professor and poet Alexander Byvshev to community service, as he had written a poem in favour of Ukrainian independence, praising Bandera's struggle against the Soviets22. In the same year, Natalya Sharina ,director of a Ukrainian library in Moscow, was arrested by the Russian authorities on charges of political extremism. The centre, which was closed down, had been set up five years earlier with the backing of the Moscow municipal authorities, with the aim of promoting Ukrainian literature in Russia. In July 2013 it had 7,000 books on its shelves. The Russian authorities accused Sharina of disseminating books promoting an ultra-nationalist ideology, citing as an example the existence of some works by Dmytro Korchinsky, founder of a Ukrainian ultra-nationalist group and accused in Russia of fighting in the Donbas23. In 2017, Sharina was convicted of inciting ethnic hatred and sentenced to four years in prison. In turn, he accused the police of rigging the evidence on the library fund24.

Since 2015, cultural and book policy in Russia has become yet another tool within the concept of national security. In the preamble to a ministerial report on the state of culture in Russia during the period 2012-2017, President Putin himself signed a presentation stressing that "preserving our identity is extremely important"25.

Russian cultural policy became a national priority within the framework of the country's political and socio-economic development, as also witnessed by the drafting in 2017 of the Economic Security Strategy of the Russian Federation for the period up to 2030. This Russian Presidency document cited culture as a battleground and a potential threat to the national security and integrity of the Russian Federation. A threat that could come from "inappropriate uses”»26.

Two years later, in 2019, Vladimir Putin claimed that 'patriotism was the only possible ideology in modern democratic society'. Thus, the historiographical narrative, embodied in literary works and essays, was to defend and disseminate Russia's power, mainly through the cult of the Great Patriotic War of 1941-194527.

Regarding Ukraine, in 2015 the "List of persons posing a threat to national security" was created. This is a list compiled by the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture at the request of the Security Service, the National Security and Defence Council and the National Council of Television and Radio, although since 2015, the Security Service has been the only body to submit names to the Ministry of Culture for inclusion. The main opposition party in the Ukrainian Rada, the Party of Regions, filed an appeal to challenge this list, but it was rejected. As of March 2022, more than 200 people are included, including actors, film directors, producers, musicians, artists and writers28.

In 2018, the Rada passed a law introduced by Petro Poroshenko's government, banning the import of books with "anti-Ukrainian content". An example of the consequence of this provision was the vetoing of the Russian edition of Stalingrad, a work by British historian Antony Beevor on one of the major battles of World War II. The book was withdrawn from bookshops and libraries because Beevor cited the collaboration of Ukrainian nationalists with the Germans29.

The gaps left by the withdrawn or censored Russian books were filled by Ukrainian authors. In 2019, a Kyiv municipal cultural programme, "measures to perpetuate the memory of Ukraine's defenders for the period up to 2020", supported the publication or reprinting of various titles to nourish the holdings of the capital's 136 libraries30.

The symbiosis achieved between the Soviet and the Russian, both contrary to Ukrainian ethnic identity, could be glimpsed in a 2018 interview with Andriy Tarasenko, head of cultural policy at Right Sector, the leading ultra-nationalist and neo-Nazi organisation. He declared that the evidence of crimes against Jews and Poles during World War II were "Soviet documents"31.

Another fact is that since 2015, reading in Ukrainian has increased dramatically and the Ukrainian publishing industry has taken off. According to the Chamber of Books, 46 million books were published in Ukrainian in 2019, compared to 5 million in Russian32. Vitalii Rybak, journalist and analyst, noted that the government had encouraged the mass publication of Ukrainian-language titles through library procurement contracts and, more significantly, that "the resurgence of the Ukrainian book industry shows that Ukraine is breaking away from the Russian cultural orbit"33.

In Ukraine, there was an exclusion of Russian-language books, while high tariffs were imposed on already difficult imports. Indeed, by 2020, 33% of Ukrainian readers chose the book according to the original language in which it was written and only 12% were indifferent to the language34.

The boycott in Ukraine of the Russian-language publishing market was important for two reasons. First and foremost because Ukraine was prepared for editorial "disengagement" from Russia. And second, this shift away from Russian cultural influence had economic repercussions. Since 2015, Russian publishers have ceased to operate in Ukraine, until then an active market. However, it should be noted that the Russian book industry is still thriving, as witnessed by the fact that in 2020 Russia was the fifth country in the world with the most books published annually, over 100,000, a testament to the demand for Russian-language reading35.

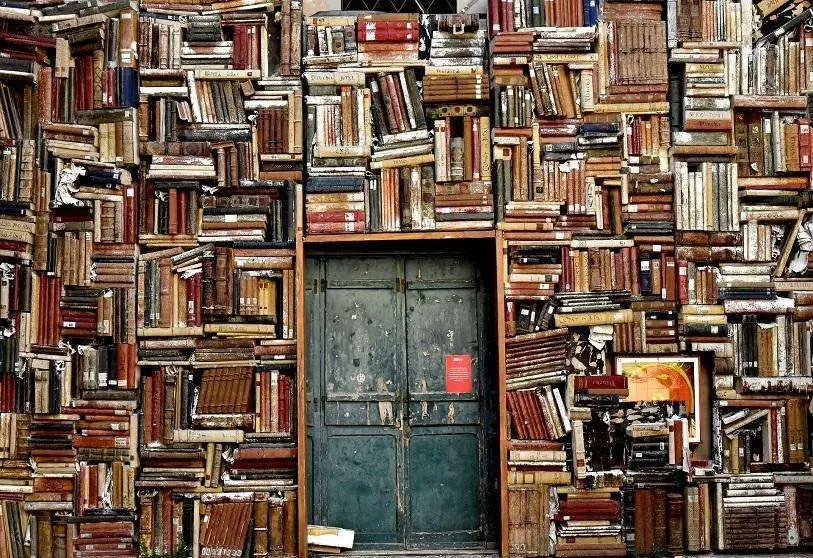

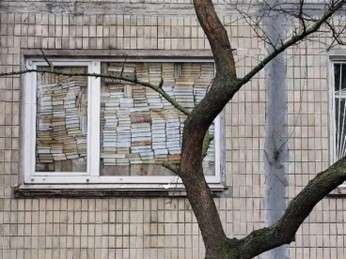

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine began in February 2022, a photograph of the Ukrainian writer Lev Shevchenko’s house in Kiev went viral on social media. To protect himself from the bombardment, the author had made a wall of books from his library up at the window. It was the image of defence against barbarism with culture and books36.

The Ukrainian authorities have banned the publication of Russian-language works, literary critic Yevheniy Stasinevych told Spanish journalist Mikel Ayestaran. This measure was justified on the grounds that publishers paid royalties "to Moscow" and that this money contributed to sustaining the Russian war effort37.

According to Ukrainian sources, dozens of libraries have been destroyed since the beginning of the war38. The director of the Ukrainian Book Institute, Oleksandra Koval, accuses the Russian military of looting bookshops and libraries to take Ukrainian- language works and destroy them, with a predilection for Ukrainian history textbooks. This in turn would justify measures against books written in Russian, as we shall see below. The Ukrainian Book Institute was founded in 2016 to promote the exclusive reading of Ukrainian authors39.

As in any conflict, cultural heritage is at risk. In March 2022, the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture launched the Saving Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Online (SUCHO) programme, in which more than 1,000 volunteer librarians, archivists and other collaborators in various parts of the country digitise works preserved in museums, libraries and archives to preserve them from possible destruction40.

These accusations by the Ukrainian authorities41, who see the country's cultural, documentary and artistic heritage at risk, have been followed by those of the pro-Russian minority, who also accuse the Ukrainian army of deliberately destroying their own heritage, including funds and collections42.

The International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) publicised the appeal by the Ukrainian Library Association (ULA) for international support and their call for a ban on all international, cultural and professional relations with Russian librarians, libraries and library associations43. ULA also urged Ukrainian public libraries to reorganise themselves into evacuee shelters, humanitarian aid collection points and information access points, sharing first-hand photos and videos from the field44.

Ukrainian cultural officials are trying to keep libraries open, where possible, and in some libraries the collections have been secured by transporting them to safer locations. Ukrainian language books have also been donated to countries such as Poland and Germany as a way of supporting their cause45. The logic of war is relentless, and the destruction of books continues. The hitherto thriving Ukrainian publishing industry has collapsed because of the disruption in sales46.

As of today, one the latest news items about the publishing world concerns the aforementioned Ukrainian Book Director, Oleksandra Koval, who in a statement to EFE announced the withdrawal from Ukrainian public libraries of more than 100 million books by Russian authors, accused of containing "imperial narratives and propaganda in favour of violence and pro-Russian chauvinist policies". This literature, described as pro- Russian, includes classic Russian authors and contemporary writers since 1991, especially those in genres such as romantic novels and crime novels. Also included are children's books, including classic Russian fairy tales47. Koval refers to the expurgation of half of the current holdings in Ukrainian libraries.

Russia's book policy has also been affected by the conflict. In January and February 2022, shortly before the invasion of Ukraine began, the Duma discussed the draft presented by the Russian Presidency with the "Fundamentals of the State Policy for the Preservation and Strengthening of Traditional Russian Spiritual and Moral Values". A strong nationalist view of Russian history was advocated, which was recommended to be reflected in the texts. On 7 February, unanimous support for the draft was received from the chamber48.

Several sources warn that an unwritten "suggestion" from the Russian government obliges authors and publishers not to mention Ukraine as an independent country from now on. After 24 February, they had to correct about 15% of the texts: "You can mention how we saved Kiev, but it is no longer possible to talk about Ukraine's independence as a country", one of these editors said anonymously49.

The rejection of the invasion of Ukraine has also meant a certain rejection of books by Russian authors50. Let’s take two examples, the first in early March when the academic authorities at the University of Milan called for the reading of the work of Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1821-1881) to be suppressed as a sign of "rejection of the war in Ukraine"51. In the same month, the prestigious International Book Fair in Guadalajara, Mexico, expelled Russian publishers from the fair for the same reason52.

After a period of cultural disputes between Russia and Ukraine, beginning with the latter’s independence in 1991, over issues such as the nationality of some authors who wrote in Russian, the conflict accelerated after the 2014 Maidan Uprising. The new Ukrainian rulers introduced an aggressive cultural policy, the basis of which consisted in prioritising the Ukrainian language over Russian and transforming the historiographical discourse to represent "Russianness", synonymous with "Sovietness", as the ancestral enemy of ethnic Ukrainians and ultimately responsible for Ukraine's real or imagined ills.

The destruction of books, the persecution of authors and the censorship of works have reached their zenith in the current war, making it possible to speak of "bibliocide" in Ukraine. This is confirmed from the Ukrainian side, as in May it was announced that one million books were to be purged from the entire country, justified as a response to the destruction of Ukrainian collections by the Russian military, creating a cultural symbiosis between the fight against the Russian occupier and the fight with Russian culture and literature.

Also from 2014 onwards, official Russian authorities began to transform the historiographical discourse on Ukraine, which was reflected in the surveillance of texts. This discourse glorifies the sacrifices of the Russian people in World War II, establishing a link between the Ukrainian ultra-nationalists' collaboration with the Germans and today's neo-Nazi organisations, while omitting any allusion to Ukrainian independence.

President Putin has expressed his literary taste for classic Russian authors53, a reading that confirms his own historiographical concept of Russia's history. Today, this union of literature and political discourse, added to the rejection of the invasion of Ukraine in Western countries, endangers the existence of these classics - more than Russian, more

than universal - in bookshops and libraries not only in Ukraine, but also in other countries allied with Ukraine in the current war.

Not unrelated to this rivalry is a struggle for the prevalence of a Russian- or Ukrainian- language publishing market in Ukraine. The legal provisions of both governments to secure their discourses and language in books have now resulted in the physical destruction of works by combatants and activists, the expurgation of funds and censorship.

This ideological ammunition against the cultural idiosyncrasies of others also has economic consequences, for while a thriving publishing industry had become present in Ukraine, it is now paralysed by the war. Meanwhile, the sector in Russia is also floundering, battered by sanctions and restrictions on its presence in international collections and forums.

But the worst of the destruction or censorship of books in Ukraine and Russia is symbolised by a more worrying risk. Recalling Heinrich Heine's axiom about the burning of books, the elimination of works harks back to past times and is a certainty of real physical danger for authors and readers, presented as enemies by the other side. A heightened danger in times of war.

For their part, the cultural poverty and manipulation of editorial discourse in Russia and Ukraine under the current circumstances seem impossible to reverse in the medium term. It is saddening to see how Ukraine's bookshops are being looted or remain closed, while libraries have become makeshift shelters for people fleeing the effects of the war, their books set aside awaiting better times, even though the bridges of coexistence and respect for a common culture appear to be broken.

Javier Fernández Aparicio

IEEE Analyst.

Bibliography

1 Las quemas iban acompañadas de recitaciones de los autores prohibidos y los títulos de las obras echadas al fuego. Más información en Fernando Báez: El Bibliocausto nazi – n.º 22 Espéculo (UCM) (consultado 14/6/2022).

2 Sobre la destrucción del patrimonio bibliográfico a lo largo de la historia véase BÁEZ, Fernando. Historia universal de la destrucción de libros. De las tablillas sumerias a la guerra de Irak. Barcelona, Destino, 2004 y POLASTRON, Lucien Xavier. Libros en llamas. Historia de la interminable destrucción de bibliotecas. México, FCE, Libraria, 2007.

3 En enero de 2013, quince yihadistas entraron en la biblioteca del Instituto Ahmed Baba de Tombuctú, se estiman que cogieron más de 4.000 manuscritos —muchos de ellos de los siglos XIV y XV— y les prendieron fuego. En Un bibliotecario de Tombuctú salvó miles de manuscritos históricos (mymodernmet.com) (consultado 15/6/2022).

4 OVENDEN, Richard. Quemar libros una historia de la destrucción deliberada del conocimiento. Barcelona, Crítica, 2021.

5 Datos para 2020 tomados de Hábitos de lectura mundiales en 2020 [Infografía] - Edición global en inglés (geediting.com) (consultado 15/6/2022).

6 Véase La otra invasión en Ucrania: obras de arte, monumentos históricos y piezas de museo en peligro - Infobae

7 TAX CHOLDIN, Marianna. Garden of Broken Statues: Exploring Censorship in Russia. Academic Studies Press, Boston, 2016, p. 65. ISBN 9781618115010.

8 «Sobre la biblioteconomía» (culture.gov.ru)

9 Ley de Ucrania sobre Publicaciones 318/97, de 5 junio de 1997. Disponible en WIPO Lex. La Ley fue modificada en algunos puntos en 2005 y 2019. El artículo 3, en lo referente a libros en ruso, continúa vigente.

10 Diez años después, en 2019, tanto el poeta como el zar Pedro el Grande fueron nombrados héroes nacionales de Rusia. Véase Putin nombra a Pushkin, Pedro el Grande entre los héroes nacionales de Rusia - Sociedad y Cultura -

11 Véase Gógol y otros iconos culturales rusos nacidos en territorio ucraniano | Cultura y entretenimiento | Agencia EFE 25/2/2022 (consultado 14/6/2022).

12 Véase KASIANOV, Georgiy. «Holodomor and the Holocaust in Ukraine as Cultural Memory. Comparison, Competition, Interaction». Journal of Genocide Research, 24:2. 2022, pp. 216-227.

13 Véase BARTOV, Omer. Borrados. Madrid, Malpaso, 2016.

14 KOPOSOV, Nikolay (op. cit.), p. 10.

15 Véase ORLAN, Susan. La biblioteca en llamas. Barcelona, Planeta, 2019, p. 102.

16 OLSHANSKAYA, Natalia. «Ukraine: Translating the wars». En LIN MONIZ, Maria & SERUYA, Teresa (eds.). Translation and Censorship in Different Times and Landscapes. Newcastle, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2008, pp. 252-261.

17 Sobre estas quemas de libros en Crimea y Járkov: La quema de libros en Ucrania aviva la controversia sobre la historia.

18 Véase Activistas y soldados se mueven para proteger las bibliotecas en Ucrania - Publishing Perspectives 14/3/2014 (consultado 15/6/2022).

19 FEDCHENKO, Anastasia. A place for REASON | The Day newspaper 11/2/2014 (consultado 15/6/2022).

20 SNAIJE, Olivia. Fintualist - Censura y libros sobre Rusia y Ucrania 25/2/2022 (consultado 14/6/2022).

21 Véase https://ula.org.ua/en/about-ula/history (consultado 15/6/2022).

22 Véase COYNASH, Halya. Russian poet sentenced over poem in support of Ukraine (khpg.org) 14/7/2015 (consultado 15/6/2022).

23 Sobre Korchinsky, véase Ucrania morirá en un sueño: Korchinsky pidió a los ucranianos una guerra de liberación nacional (news-front.info) 29/4/2019 (consultado 15/6/2022).

24 Véase OSBORN, Andrew. Head of Moscow's Ukrainian library convicted of incitement against Russians | Reuters 5/6/2017 (consultado 15/6/2022).

25 Véase EFREMOVA, L., RUSETSKIY, M., MOLCHAN, A., LECHMAN, E., & AVDEEVA, R. «Russian Cultural Policy:

Goals, Threats, and Solutions in the Context of National Security», Journal of History Culture and Art Research, 7(3), 2018, pp. 433-443.

26 On the Strategy of Economic Security of the Russian Federation for the period up to 2030 | Presidential Library

(prlib.ru)

27 KOSOPOV, Nikolay. «“The Only Possible Ideology”: Nationalizing History in Putin’s Russia», Journal of Genocide Research, 24:2, 2022, pp. 205-215.

28 Véanse nombres, referencias y enlaces en la Wiki: Перелік осіб, які створюють загрозу нацбезпеці України — Вікіпедія (wikipedia.org) (consultado 17/6/2022).

29 Véase Ucrania censura la distribución del libro ‘Stalingrado’ del historiador británico Anthony Beevor - mpr21 14/5/2018 (consultado 17/6/2022).

30 Departamento de Comunicaciones Públicas del Ayuntamiento de Kiev. Lista de libros de acuerdo con el programa objetivo de la ciudad para el desarrollo de la esfera de la información y la comunicación: https://dsk.kyivcity.gov.ua/content/perelik-knyg-2019-2021.html (consultado 17/6/2022).

31 Véase PIWOWAR, Pawel. Should Poles be afraid of the Right Sector? A Polish journalist found out - Euromaidan Press 22/2/2018 (consultado 17/6/2022).

32 Los informes y datos de publicación de monografías y publicaciones periódicas se pueden consultar en la página web de la Cámara del Libro de Ucrania: Книжкова палата України (ukrbook.net) (consultado 16/6/2022).

33 RYBAK, Vitalii. Reading in Ukrainian: The Resurgence of the Ukrainian Book Industry (ukraineworld.org) 18/2/2022

34 BONET, Pilar. La guerra alcanza la literatura ucraniana | Babelia | EL PAÍS (elpais.com) 13/3/2020 (consultado 16/6/2022).

35 China era el país con mayor número de publicaciones anuales, alcanzando las 440.000. Datos tomados de Hábitos de lectura mundiales en 2020 [Infografía] - Edición global en inglés (geediting.com) (consultado 15/6/2022).

36 Véase La improvisada trinchera de un escritor ucraniano arrasa en las redes sociales (cadenaser.com) 6/3/2022.

37 Recogido en SERRANO, Pascual. Prohibido dudar. Las diez semanas en que Ucrania cambió el mundo. Akal, Madrid, 2002, p. 54.

38 Existe un proyecto de la Fundación Cultural de Ucrania para cartografiar los monumentos y enclaves culturales destruidos por la guerra. La Asociación de Bibliotecas de Ucrania estima en más de 200 las bibliotecas destruidas. Disponible en Culture loss map - Ukraine. Culture. Creativity (uaculture.org) (consultado 16/6/2022).

39 Véase Las autoridades de Ucrania proponen eliminar 100 millones de libros rusos de sus bibliotecas - Infobae 23/5/2022 (consultado 16/6/2022).

40 Web con información: Saving Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Online | SUCHO (consultado 16/6/2022).

41 RUKOMEDA, Román. ‘Russia burns our books hoping to destroy our nation’ – EURACTIV.com 25/3/2022 (consultado 16/6/2022).

42 En marzo de 2022, la comisionada de derechos humanos del Parlamento ucraniano, Liudmyla Denisova, acusó a las fuerzas rusas de confiscar y destruir libros de literatura e historia en zonas ocupadas del país, pero no se hablaba de las denuncias, sobre todo en redes sociales, de la minoría prorrusa sobre la destrucción del patrimonio documental y artístico ruso en Ucrania. Véase Ucrania acusa a las fuerzas rusas de confiscar y destruir libros en zonas ocupadas (eldiario.es) 25/3/2022 (consultado 17/6/2022).

43 Véase la información en la propia web de la IFLA: IFLA response to the situation in Ukraine – IFLA 21/3/2022 (consultado 16/6/2022).

44 Véase Librarians! Stand with Ukraine! / Бібліотекарі! Будьмо з Україною! - Ukrainian Library Association

45 Véase CHAPPELL, Bill. Ukraine's libraries are offering bomb shelters and camouflage classes: NPR 9/03/2022 (consultado 16/6/2022).

46 Véase La industria editorial ucraniana trastornada por la invasión rusa: NPR (101noticias.com) (consultado 16/6/2022).

47 Véase Bibliotecas ucranianas podrían retirar los libros rusos después de tres meses de conflicto armado - Infobae 26/5/2022 (consultado 16/6/2022). La entrevista original a Koval en https://interfax.com.ua/news/interview/834181.html 23/5/2022 (consultado 17/6/2022).

48 Toda la información sobre esta iniciativa en la web del Ministerio de Cultura de la Federación de Rusia: Actividades

- Ministerio de Cultura de la Federación de Rusia (culture.gov.ru) (consultado 16/6/2022).

49 Véase Borrar a Ucrania de los libros de texto, la orden de las autoridades rusas a su principal editorial educativa | DIARIO DE CUBA 23/4/2022 (consultado 15/6/2022).

50 Véase NARBONA, Rafael. Dostoievski y la guerra de Ucrania (elespanol.com) 29/3/2022 (consultado 17/6/2022).

51 GARCÍA, Concha. Polémica en Italia por cancelar a Dostoievski como rechazo a la guerra en Ucrania (larazon.es) 10/3/2022 (consultado 16/6/2022).

52 Véase Taibo II denunció censura de la FIL de Guadalajara a los libros rusos: «Es un boicot a la cultura» (lapoliticaonline.com) 11/3/2022 (consultado 16/6/2022).

53 Véase GUZEVA, Alexandra. Los 10 libros y escritores favoritos de Vladímir Putin - Russia Beyond ES (rbth.com)