The importance of Land Corridors (II): The Iranian's race to the Mediterranean Sea

Zbigniew Brzezinski defined Iran's importance as a geopolitical pivot, the genuine possibility of it becoming a geopolitically active player being added to this1. Some time later Robert Kaplan confirmed these ideas by highlighting Iran's role as the bulwark and sole actor controlling the Gulf and Caspian resource basins. In relation to Mesopotamia, Kaplan considered that from the stronghold of the Iranian Zagros Mountains one could easily descend on to the western regions, where Shiism is a factor of cohesion with the non-Iranian minorities professing the different branches of this religious confession2. Michael Axwothtry was one of the authors who further elaborated on the Iranian geopolitical concept, when he state that Iran was far more about culture and language than race and territory, in a clear allusion to the historical, customary, linguistic and religious ties that bind the people of Iran to other inhabitants of the Middle East3.

Iran is also seen by Orientalist researchers as a core of radiating power. Vladimir Sahzin, in addition to agreeing with the previous authors, believes that the Iranians are seeking regional power status along several strategic lines. These lines would eventually make it a become a pan-Islamic world centre, achieve regional leadership and create internal stability4.

For the Iranians themselves, these ideas are supported by nationalist trains of thought, which use the term Iranshahr (Iran's rule) as the recovery of the territories that stretched from the Oxus River (Amur Darya) to the Euphrates basin5. One of the main promoters of these theories is Professor Ali Massoud Ansari, although it must be acknowledged that this trend has its roots in the historian and politician Hassan Pirnia. This vision of Iran's future was seen by Professor Ruhi Ramazani as idealistic in its external goals,. Having said that, the steps to reach them were eminently practical6.

Transposing these concepts to recent times, Iran possessed a structure that facilitated its westward expansion, due to the fact that it had created the Badr Organisation in the 1980s, during the war with Iraq, as a set of Shia militias in Iraqi territory, in whose formation former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was actively involved. The leadership of this organisation relied on the Qods Force of the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guards, or Pashdaran.

The natural tendency of geopolitics in Iran became more marked after US forces liberated Iran from the Iraqi threat of Saddam Hussein in 2003. The disbanding of Saddam's Ba'ath party followers led to a new order in which Iraqi Shi'ites became more prominent in the face of Sunni and Kurdish frustration. In this situation, pro-Iranian militias and Pashdaran infiltrated the political, administrative, social and security structures of the new Iraq in which the pro-Iranian Shiite Nuri al-Maliki would hold the post of prime minister until 2014.

Since the fall of Saddam, Iran has once again had the opportunity to look to Mesopotamia and the Levant as one of the areas where it can extend its influence, although the US, Saudi Arabia and Israel have tried to prevent this, while other actors such as Russia and Turkey have tried to shape this trend to their convenience. China also became interested in the region, where it could implement its Belt and Road project through the Iranians.

The so-called 'Arab Springs' that affected Syria in 2011 provided another new opportunity to continue extending Iranian influence in the region. In this instance, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad found it necessary to turn to the Iranians in order to prop up his ailing regime, to whose call Iran came in exchange for turning Syria into a satellite state. Assad would become dependent on Iranian aid, which reached him by air from 2012 onwards, some of which was transported overland to Lebanon7.

Iran's presence in Iraq and Syria brought it closer to one of its most loyal allies in the region, as Hassan Nashrallah, the leader of Hezbollah in Lebanon, had in his youth sworn allegiance to the then Iranian leader Ayatollah Khomeini.

After the proclamation of the Islamic caliphate in Mosul by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in 2014 and the expansion of Daesh, the new Iraqi army collapsed like a house of cards. In the face of Daesh's push, virtually all that was left were the Shia militias, which grouped together and went under the name of the Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF). In the meantime, a new US-led multinational coalition was created and there was an overhaul of the Iraqi armed forces. Then Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi granted the PMFs legal status, which would ultimately consolidate the power of these forces after the military defeat of Daesh in late 20178.

There is growing Iranian activism in the Middle East despite efforts by the US and its allies to weaken Iran's economy and isolate Tehran politically. There has been an increase in the size and capabilities of militias supported by the Quds Force of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Yemen. Iran is also working to establish a land bridge in the region. However, Iran has weaknesses and vulnerabilities that can be exploited by US partners and other actors.

Iran has established a series of its own alliances and activities to create a land bridge in a westerly direction through a series of corridors, the whole of which is often referred to by groups operating in the area as Wilayat Imam Ali, which could be translated as the province of Imam Ali, son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad9. Alliances and efforts along these communication pathways are often referred to as the "axis of resistance", a concept that is being reinforced every day10.

In late 2016, Sunni Arabs began to fear that, after the defeat of Daesh, something more dangerous would follow in its wake like "a land corridor from Tehran to Beirut"11. This concept was not yet developed but, in view of the results on the ground, during 2018 the Iranians and their allies reached a consensus on its creation, although they were still debating how significant it could be12. However, it is possible that the Iranians had long kept this plan under wraps until they had the opportunity to implement it. The architect of its preparation and coordination was probably General Qassem Soleimani13.

The usefulness of this bridge would be based on three complementary purposes: On the one hand, it would provide a cheap transport route for the shipment of arms to the Mediterranean for its partners; it would also be an alternative route to the Iranian air bridge in the region, in the event of Israel bombing any of the airports on which the Iranians rely for their supply chain; finally, it would serve to reaffirm the Shiite identity in the whole region through a communication channel for the exchange of all kinds of products and to link related communities scattered throughout the Middle East14.

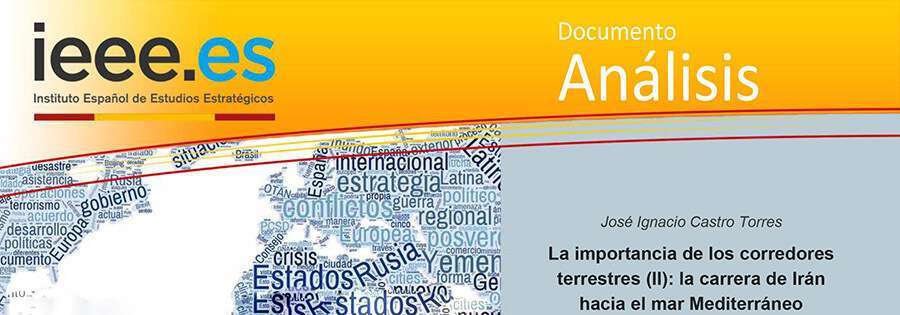

The bridge would be divided into two main routes. The northern route would go through the Kurdish region of Iraq to Kirkuk, Erbil and from there to Mosul and Rabia, near the Syrian border. Once on Syrian territory, the M4 highway, which runs parallel to the Turkish border, can directly access the Aleppo communications hub and the air base and port of Latakia, where there is a Russian and Iranian presence. From Aleppo to Homs there are excellent communications via the M5 and then a corridor can lead to Beirut in Lebanon.

The southern route would run through central Iraq and from Baghdad along Iraqi Highway 1 to reach Al Tanf, just across the Syrian border, from where it can link directly to Damascus and Beirut.

A third route, or an alternative corridor to the southern route, could be considered, following the Euphrates River to the Iraqi border at Al Qaim and into Syria from Abu Kamal, possibly reaching as far as Dier ez Zor and the Homs communications hub. From here you can then reach the port city of Tartus, where Russia maintains its main naval presence in the Mediterranean.

There is the possibility of linking both main routes, continuing all along the Euphrates River to Aleppo

Israel considers itself directly affected by the existence of the bridge, as a multitude of weapons can easily be transported across the bridge to Syria and Lebanon and then sent to the Palestinian territories. Consequently in 2018 President Netanyahu declared that this bridge would trace a route from "Tehran to Tartus in the Mediterranean", allowing Iran to "attack Israel from close range"15. Throughout 2019, the bridge would suffer several attacks that could not be linked to anybody, although the then Iraqi security adviser, Abu Mehdi Al-Muhandis16, claimed that they were carried out by "agents or by special operations with modern aircraft"17.

During 2020, the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) provided documentation to demonstrate collusion between militias and pro-Iranian governments. One of the most significant pieces of evidence was the meeting between Hezbollah's Golan leader, Hajj Hashem, and Syrian General Ali Amad Assad. Based on the various pieces of evidence, the IDF has conducted numerous interventions in Syria against Qods Force-related facilities. Moreover, they have declared that they will not tolerate any Iranian presence on Israel's borders and will continue to act to keep Israel safe from Iranian, Hezbollah and Syrian aggression"18.

These attacks have continued throughout 2021 on allegedly Iranian-linked logistics facilities and arms convoys bound for Hizbullah in Lebanon, the most notable incident being the killing of eight Iranian Revolutionary Guardsmen in Syria's Latakia and Hama provinces in May. However, the Israelis have not increased interventions on other targets, this probably in order to keep a possible Hezbollah backlash contained. This Shia organisation probably does not want to trigger a massive Israeli response that would open a new front in Lebanon, when the country is going through a difficult economic and political situation19.

There seems to be no indication that either Iran or Israel can change their stances, as both consider themselves to have vital security interests in the Syrian conflict. For the Israelis, Iranian support for Hezbollah is a constant source of concern, which has been aggravated by the growing Iranian presence in Syria. Meanwhile, the new negotiations that have opened over Iran's nuclear programme have heightened Israeli as well as

possibly Saudi fears. If there were to be some kind of agreement that favoured the Iranians, they could see their sanctions reduced and their missile programme revitalised, and the current precarious balance could be dangerously shaken20. It remains to be seen whether in future nuclear negotiations these missiles will be bargaining chips.

In the meantime, Turkey sees new possibilities as a moderator in the region, as it can support the different actors in the region by compensating for the Iranian presence. Although Turkish and Iranian relations have been good in recent years, they have cooled recently due to Turkish support for the Azeris in Nagorno-Karabakh. The Turks have also distanced themselves from the Iranians in their perception of the Syrian conflict in the Iblib pocket (where Turkish forces clashed with Hezbollah members) and have taken issues that could be discussed at the Astana talks to a bilateral level with Russia, which excludes Iran. Another incongruent development has been Turkish contacts with Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Israel, which have put Iranian diplomacy on alert21, 22.

However, the Turks and Iranians have convergent positions on the Kurdish issue. The Turks do not trust the US after it helped the Syrian Kurds in their fight against Daesh. It therefore appears that Iranian influence in the area could be a security booster for Turkey's southern border23.

Far from the problems regional actors have on the ground, China sees the possibility of using Iran's westward communications as an opportunity to increase the connectivity of its own Silk Road and Belt and Road branches. At the same time, the region is of interest

to the Chinese energy needs, as Iraq has significant oil fields from which they are already benefiting, as well as Iranian resources.

In 2018 Iran announced that it intended to build a rail line connecting the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean Sea from Iraq's Basra and across the border at Abu Kamal, then into Syria to Deir ez-Zour. Accordingly, "if the railways are connected between the three countries, it will be another important step to connect Chinese railways to the Mediterranean Sea through Iran, Iraq and Syria"24.

At the end of that year, the three countries reached a tentative pre-agreement to build a railway line and a motorway from Basra to the Syrian port of Latakia on the Mediterranean coast. The first phase was the most modest step and aimed to link Iran with Iraq via a 32 kilometre railway line between the cities of Shalamcheh and Basra25. In 2021, the construction of the railway line between the two cities is about to start, connecting to the Iranian railway system26.

This first phase has been widely welcomed by the Iranian authorities, with President Hassan Rohani stressing that the railway will bring significant change to the region. Following the announcement of the opening of an Iranian consulate in Aleppo by Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Jawad Zarif, it seems that the next steps to the Mediterranean are possible, as their construction would fall within the framework of the Memorandum of Understanding recently signed between China and Iran27.

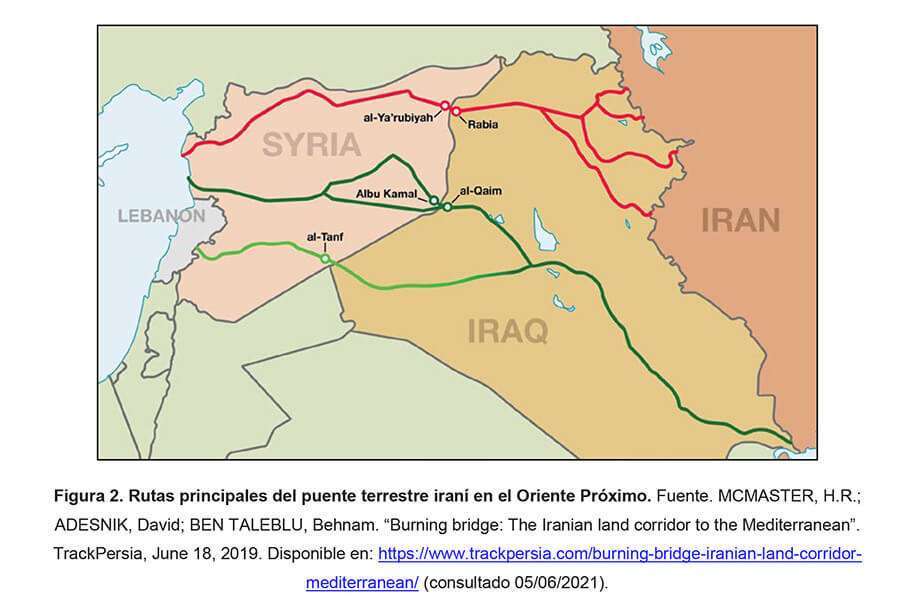

Russia has an interest in establishing a land bridge across the Middle East, not only for the sake of a continued presence at the Tartus naval base, but also as a means to minimise the phenomenon of Jihadism and prevent it from spreading in its areas of influence in the Caucasus and Central Asia, as well as within its borders, notably in Chechnya28.

Russia sees Turkey as an expanding regional power, which clashes with its interests precisely in the Caucasus and Central Asia, where the Turks have played a prominent role in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict29.

Russia also believes that Turkey can compete against Russian gas sales in Europe. It must therefore control the energy distributor that is the Anatolian Peninsula, seeking to surround it with its presence or that of its partners. In the north, Georgia has been contained since the 2008 conflicts and both Armenia and Azerbaijan have been more controlled since the 2020 disputes30. This situation forces the Azeris and Central Asian countries to negotiate with Russia for the delivery of their energy products. Turkey is also inclined to agree with Russia on the distribution of these products through its territory.

The discovery of gas off the coast of the Eastern Mediterranean makes it competitive with Russia in the European market. If the Russians succeed in limiting Turkish influence to the south, they could prevent the Turks from controlling energy products in the Mediterranean, for which they clearly compete in Libya31. To this end, the establishment of the Iranian land bridge would strengthen Russia's presence and give greater power to its Iranian and Syrian partners, which would be Turkey´s loss.

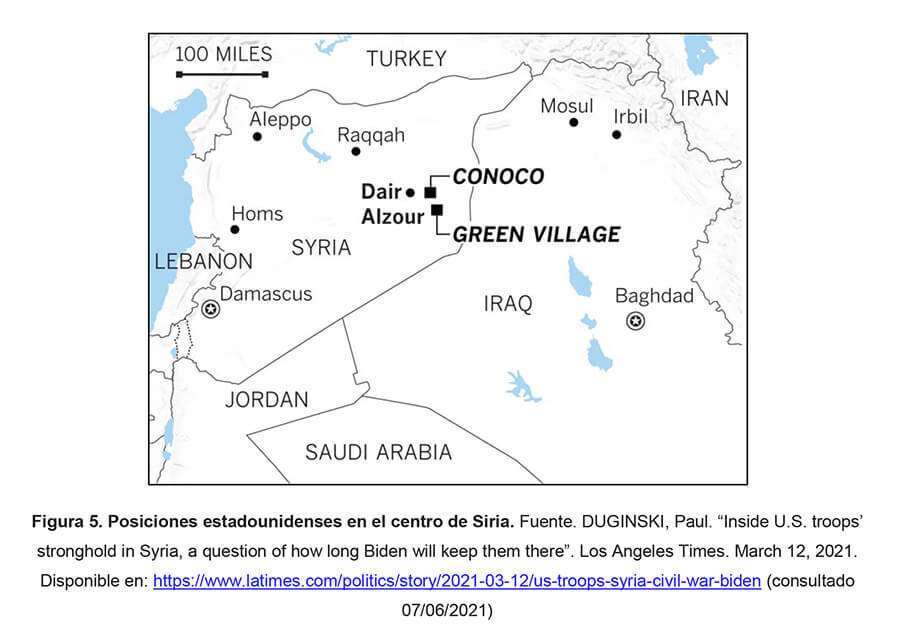

The US The US maintains a "small" contingent of approximately 900 military personnel in Syria, which President Biden appears to be in no hurry to withdraw. From their main positions they have the ability to reach the eastern bank of the Euphrates River controlled by the blend of Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) militias allied with the Kurds in Rojava35. On the other side are Russian and Syrian government troops36.

Despite US rhetoric about supporting local militias in their fight against Daesh and humanitarian assistance to the civilian population or the protection of oil resources, the fact is that these positions in Syria straddle the central branch of the Iranian land bridge, and consequently US forces have the ability to control this communication route on the ground.

In a similar situation is a small outpost at Al Tanf, on the road between Baghdad and Damascus and close to the tri-border area. The Americans have recognised that they can exert pressure on Iran's westward communications by denying it the use of the southern land bridge route, which has led to skirmishes with pro-Iranian militias on several occasions. US troops are coordinating with the Syrian rebel group Maghawir al-Thawra, which drove Daesh out of the area it now controls. Restricted in their freedom of movement, Daesh forces mingled with the 100,000 Bedouin living in the area, where the Rukban refugee camp is located37.

The situation of US armed forces in Iraq shows a significant combat capability centred on the Baghdad communications hub that supports forward positions in Syria. The Skyes Forward Operating Base at Tall'Afar closes the mobility corridor in the northern part of the land bridge.

It should be noted that after Soleimani's death by the Americans, the Iraqi government requested his withdrawal by means of a non-binding resolution. Following diplomatic talks between the US and Iraqis in the spring of 2021, it was concluded that Iraqi security forces had increased their capabilities and that US combat forces could withdraw. This has changed their status to advisory forces, but the reality is that 2,500 military personnel currently remain on Iraqi soil38.

With no firm bet yet on the future of the US presence in Iraq, the Biden administration will have to make an important decision on its continuing involvement, at the risk of using tactical thinking for strategic decisions.

This short-term thinking can lead to major mistakes, underestimating Iraq's importance because there is no longer US dependence on its oil resources, although there is dependence on other actors such as China. For the Americans, Iraq's significance should not be to focus on fighting the Daesh insurgency, but rather to contain and deter Iran in order to prevent Iraq from becoming a strategic bridge linking the Iranians to Syria and Hezbollah and, in the longer term, potentially destabilising Jordan and the Gulf Arab states. American influence in Iraq would also be a check on Turkish interference and a barrier to Russian and Chinese influence39.

Iran's natural geopolitical tendency is to expand from its mountainous stronghold into the flatter areas of Mesopotamia and the Levant. Throughout the region there are many Iranian-friendly populations, who are not currently constrained by the actions of authoritarian governments.

The Levantine chessboard is extremely complex and whoever knows the intricate moves of its pieces is likely to have the advantage over the rest of the players involved. General Qassem Soleimani knew exactly how to use the sectarianism in the area over and above the administrative structures, which are often no more than a mere façade with which Westerners unsuccessfully try to engage.

Iran's long-term plans possibly include liaising with areas favourable to its expansion, so it needs a network connecting these to extend its influence through instruments of diplomatic, informational, military and economic power as an actor in a conflict, to which should be added the political power of the Iranian state and the social power of its culture. This requires the establishment of a land bridge that can increase what the Iranians see as the "axis of resistance".

This extension is intended to come at the cost of causing an existential risk to other actors in the region, such as the Arab or Kurdish populations of the Middle East or the State of Israel itself, so Iranian pretensions must be carefully measured to avoid miscalculations. Therefore, although its ultimate goal is extremely idealistic, the steps to be taken are cautious and pragmatic.

Iranian objectives also overlap with those of other state actors in the region, most notably Turkey's utilitarian role and the opposition of Israel and the Gulf states, thus creating a conglomerate of volatile alliances that easily shift as events unfold.

To further complicate matters, the role of global powers is very significant in the area. Chinese and Iranian interests seem to go hand in hand, as the Iranian land bridge favours China's Silk Road and Belt initiative, while also providing access to energy resources. This is why China is expected to be increasingly active.

Russia has its own agenda, so the Iranian land bridge serves to regain its status in the Mediterranean and control Turkey's energy corridor, while it can prevent the Turks from coming into conflict with Russian interests in Libya, the Caucasus and Central Asia.

The US is at a crucial moment to make a determination to regain the long-term initiative, which the Iranians have always had. If the United States were to consider a withdrawal from the area, it would be facilitating Iranian interests, as well as those of the Russians and Chinese. If it were to keep a firm foot on the ground, it would run the risk of wearing itself out in efforts that, as so far, have not yielded the benefits expected- A strategy of containing the Iranians and balancing the rest of the actors could be less costly and more practical, although it would have to change its short-term objectives to more distant ones such as stabilising Iraq through effective programmes that prevent institutional corruption and improve the capabilities of Iraq's security forces. Cooperation with Turkey would also serve this purpose, rather than its current alliance with the Syrian PYD.

The European Union has been largely absent from an issue in which, given its own idiosyncrasies, it could play a much more active role. Europeans are good negotiators and have a formidable capacity for understanding and dialogue, so they could play an extraordinary role as go-betweens among all actors, which could well include Iran, which, thanks to European mediation, is in the process of negotiating its nuclear programme. Of course, the gains for the old continent could be significant, as they would raise the spectre of jihadism, as well as migration crises, and could lead to diversity of access to energy products, which could result in lower costs and control of suppliers.

José Ignacio Castro Torres*

COR.ET.INF.DEM

PhD in Peace and International Security Studies

IEEE Analyst

- 1 BRZEZINSKI, Zbigniew. The grand chessboard: American primacy and its geostrategic imperatives. Basic books, 1997. p. 41.

- 2 KAPLAN, Robert D. The revenge of geography: What the map tells us about coming conflicts and the battle against fate. Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2013. pp. 267-272.

- 3 AXWORTHY, Michael. A history of Iran: Empire of the mind. Basic Books, 2016. p. 3.

- 4 SAZHIN, Vladimir. Iran seeking Superpower status. Russia in Global Affairs, 2006, vol. 1. pp 152-160.

- 5 ANSARI, Ali M. The politics of nationalism in modern Iran. Cambridge University Press, 2012. pp. 298- 300.

- 6 RAMAZANI, Rouhollah K. “Ideology and pragmatism in Iran's foreign policy”, The Middle East Journal

- 7 FULTON, Will; HOLLIDAY Joseph; WYER, Sam. “Iranian Strategy in Syria”, American Enterprise Institute and Institute for the Study of War, May 2013. pp. 15-19.

- 8 MAJIDYA, Ahmad. “Iran-backed militia groups will receive full military benefits under new decree”, Middle East Institute, March 9, 2018. Disponible en: https://www.mei.edu/publications/iran-backed-militia-groups- will-receive-full-military-benefits-under-new-decree (consultado 05/06/2021)

- 9 GHADDAR, Hanin; SMYTH, Phillip. "Rolling Back Iran's Foreign Legion", The Washington Institute. 6 de febrero de 2018. Disponible en: https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/rolling-back-irans- foreign-legion (consultado 05/06/2021)

- 10 AHMADO, Nisan. “Experts: Iran Eyes Reuniting Its 'Axis of Resistance”, VOA, January 27, 2021. Disponible en: https://www.voanews.com/extremism-watch/experts-iran-eyes-reuniting-its-axis-resistance (consultado 06/06/2021)

- 11 TROFIMOV, Yaroslav, “After Islamic State, Fears of a ‘Shiite Crescent’ in Mideast”, The Wall Street Journal, September 29, 2016. Disponible en: https://www.wsj.com/articles/after-islamic-state-fears-of-a- shiite-crescent-in-mideast-1475141403 (consultado 05/06/2021)

- 12 MCMASTER, H.R.; ADESNIK, David; BEN TALEBLU, Behnam. “Burning bridge: The Iranian land corridor to the Mediterranean”, Foundation for Defense of Democracies. Disponible en: https://www.fdd.org/analysis/2019/06/18/burning-bridge/ (consultado 06/06/2021)

- 13 CHULOV, Martin “Amid Syrian chaos, Iran’s game plan emerges: a path to the Mediterranean”, The Guardian, October 8, 2016. Disponible en: https://theguardian.com/world/2016/oct/08/iran-iraq-syria-isis- land-corridor (consultado 06/06/2021). Para ver en detalle la importancia que Soleimani tuvo en la configuración de la región se sugiere la lectura del siguiente documento: CASTRO TORRES, José Ignacio. Qassem Soleimani: El liderazgo desde el otro lado de la colina. Documento de Análisis IEEE 33/2019. Disponible en:

- http://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_analisis/2019/DIEEEA33_2019CASTRO_Soleimani.pdf

- 14 Ibid. hay que tener en cuenta que Irán transporta por vía aérea a Siria una gran cantidad de personal y materiales de gran interés para el régimen de Asad.

- “Full text of Netanyahu’s 2018 address to AIPAC”, The Times of Israel, 6 March 2018. Disponible en: https://www.timesofisrael.com/full-text-of-netanyahus-2018-address-to-aipac/ (consultado 06/06/2021)

- 16 Abu Mehdi Al-Muhandis fue uno de los líderes de la milicia Hashed Al Shaab y murió junto a Qassem Soleimani en Bagdad a principios de 2020. Para una mayor información sobre este hecho se sugiere la lectura del siguiente documento: CASTRO TORRES, José Ignacio. Qassem Soleimani: Una muerte que abre la caja de Pandora. Documento Informativo IEEE 01/2020. Disponible en: http://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_informativos/2020/DIEEEI01_2020CASTRO_SoleimaniMuerte. pdf

- 17 AHRONHEIM, Anna. “Israeli satellite imaging shows how Iran’s land bridge is under attack”, August 22, 2019. Disponible en: https://www.jpost.com/middle-east/israeli-satellite-imaging-irans-land-bridge-is- under-attack-599410 (consultado 06/06/2021)

- 18 “Hezbollah in Syria: What You Should Know”, IDF. Disponible en: https://www.idf.il/en/minisites/hezbollah/hezbollah-in-syria-what-you-should-know/ (consultado 06/06/2021)

- 19 “Why Iran absorbs Israeli-inflicted blows on its militant proxies in Syria”, Arab News, May 16, 2021.

- 20 WIMMEN, Heiko “Syria: How to prevent Israel-Iran shadow war spinning out of control”, Middle East Eye,

- 10 May 2021. Disponible en: https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/syria-israel-iran-shadow-war-how- keep-control (consultado 06/06/2021)

- 21 DALAY, Galip. “Turkish-Iranian Relations Are Set to Become More Turbulent”, German Marshall Fund, February 9, 2021.. Disponible en: https://www.gmfus.org/publications/turkish-iranian-relations-are-set- become-more-turbulent (consultado 06/06/2021)

- 22 SAIDEL, Nicholas. “Israel Needs a Reset With Turkey to Contain Iran”, Haaretz, Mar. 24, 2021. Disponible en: https://www.haaretz.com/middle-east-news/.premium-israel-needs-a-reset-with-turkey-to- contain-iran-1.9650545 (consultado 06/06/2021)

- 23 BEHRAVESH, Maysam. “How Iran views the Turkish invasion of northern Syria”, Middle East Eye, 12 October 2019. Disponible en: https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/how-iran-views-turkish-invasion-

- 24 "هکبش یلیر ناریا هب یاهروشک قرش هنارتیدم لصو یم دوش /La red ferroviaria de Irán se conecta a los países del Mediterráneo oriental", IRNA, 18 de agosto de 2018. Disponible en: http://www.irna.ir/fa/News/83004528 (consultado 06/06/2021)

- 25 “Iran-Iraq-Syria Plan to Move Ahead on Historic Transnational ‘Land-Bridge’ Railroad”, The International Schiller Institute (consultado 06/06/2021)

- 26 “Iraq Ties Itself to China Via Belt & Road Rail Links Between Basra and Iran’s Shalamcheh”, Silk Road Briefing, May 19, 2021. Disponible en: https://www.silkroadbriefing.com/news/2021/05/19/iraq-ties-itself-to-

- 27 “Rouhani Says Shalamcheh-Basra Railway to Connect Iran to Iraq, Syria, and the Mediterranean”, Asharq Al-Awsat, Friday, 14 May, 2021. Disponible en: https://english.aawsat.com/home/article/2972166/rouhani-says-shalamcheh-basra-railway-connect-iran- iraq-syria-and-mediterranean (consultado 06/06/2021)

- 28 BLANK, Stephen. The Foundations of Russian Policy in the Middle East, en: Russia in The Middle East (Theodore Karasik and Stephen Blank, Eds). The Jamestown Foundation. Washington, DC. 2018. p.40. 29 Para un estudio en mayor detalle de los intereses geopolíticos en el Cáucaso se sugiere la lectura del siguiente documento: CASTRO TORRES, José Ignacio. Nagorno Karabaj: un nudo gordiano en mitad del Cáucaso. Documento de Análisis IEEE 34/2020. Disponible en: http://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_analisis/2020/DIEEEA34_2020JOSCAS_Nagorno.pdf

- 30 KEMOKLIDZE, Kakhaber; SESKURIA, Natia. “Targeting Turkish–Georgian Relations: Russian Disinformation is Taking a Local Turn”, RUSI, Commentary, 20 May 2021. Disponible en: https://rusi.org/commentary/targeting-turkish-georgian-relations-russian-disinformation-taking-local-turn

- 31 RUMER, Eugene; SOKOLSKY, Richard. “Russia in the Mediterranean: Here to Stay”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. May 27, 2021. Disponible en: https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/05/27/russia-in-mediterranean-here-to-stay-pub-84605 (consultado 07/06/2021) No obstante, en este punto se abre una disyuntiva para Rusia, por haber sido excluida del reparto de la explotación de los recursos del Mediterráneo. Dependiendo cómo evolucionen los acontecimientos podría darse el caso en que rusos y turcos colaborasen por una confluencia puntual

- 32 “Trump orders US troops out of northern Syria as Turkish assault continues”, The Guardian, 13 Oct 2019. Disponible en: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/oct/13/trump-us-troops-northern-syria-turkish- assault-kurds (consultado 07/06/2021)

- 33 WILLIAMS, Katie Bo. “In Syria, US Commanders Hold the Line - and Wait for Biden”, Defense One, March 21, 2021. Disponible en: https://www.defenseone.com/threats/2021/03/syria-us-commanders-hold- line-and-wait-biden/172808/ (consultado 07/06/2021)

- 34 “USAID ‘Syria Program”, COMBINED JOINT TASK FORCE OPERATION INHERENT RESOLVE Public

- Affairs Office, April 27. #LifeAfterDaesh. Progress highlights in Iraq and Syria. Disponible en: https://www.inherentresolve.mil/Portals/14/CJTF-OIR%20Press%20Release-20210506-01- Life%20After%20Daesh%20Highlights.pdf (consultado 07/06/2021)

- 35 Para un estudio en mayor detalle de las relaciones entre los distintos grupos de la zona se sugiere la lectura del siguiente documento: SÁNCHEZ TAPIA, Felipe. Conflictividad en la frontera sur de Turquía. Panorama Estratégico de los Conflictos 2020. Instituto Español de Estudios Estratégicos. pp. 83-116.

- 36 CLOUD, David S. “Inside U.S. troops’ stronghold in Syria, a question of how long Biden will keep them there”, Los Angeles Times. March 12, 2021. Disponible en: https://www.latimes.com/politics/story/2021-03- 12/us-troops-syria-civil-war-biden (consultado 07/06/2021)

- 37 MAGRUDER, Daniel L. Jr. “Al Tanf garrison: America’s strategic baggage in the Middle East”, Brookings, Friday, November 20, 2020. Disponible en: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from- chaos/2020/11/20/al-tanf-garrison-americas-strategic-baggage-in-the-middle-east/ (consultado 07/06/2020)

- 38 LOVELUCK, Louisa. “U.S. and Iraq conclude talks on troop presence”, The Washington Post, April 7, 2021. Disponible en: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/us-iraq-talk-troops/2021/04/07/e9a15998- 97cb-11eb-8f0a-3384cf4fb399_story.html (consultado 07/06/2021)

- 39 CORDESMAN, Anthony H. “Correcting America’s Grand Strategic Failures in Iraq”, Center for Strategic and International Studies. April 1, 2021. Disponible en: https://www.csis.org/analysis/correcting-americas- grand-strategic-failures-iraq (consultado 07/06/2021)