The pandemic is still here

The figures that reach us every day clearly indicate that the COVID-19 virus, despite the advances in the vaccination process in the most developed countries, is still on the prowl and ready to take every opportunity to continue wreaking havoc. Figures available on 12 November indicate that there have been more than 252 million infections, almost 5.1 million people have died and there are 19 million active cases (equal to total cases minus the sum of deaths and recoveries) of which a significant fraction (2.01%) will die. Obviously, these figures grossly underestimate the incidence of the disease, either because of a lack of resources or government inaction to refine counts and figures, or because the authorities are interested in presenting a sugar-coated image of their management.

To be specific, it is not credible, for example, that only 4 people have died in China since 17 April 2020 at the end of the original outbreak of the epidemic in Wuhan. Nor is it credible that the number of cases per million inhabitants in Turkey and Iraq, 97,464 and 70,446 respectively, are so much lower than in the United States (143,088) or even Spain (107,809), and the number of deaths per million inhabitants in Turkey and Iran, 852 and 1496 respectively, are so far from those in the United States (2343) and Spain (1874). But, in the end, these are the official data collected in international statistics and should be followed, except when we have additional information that allows us to refine the official figures.

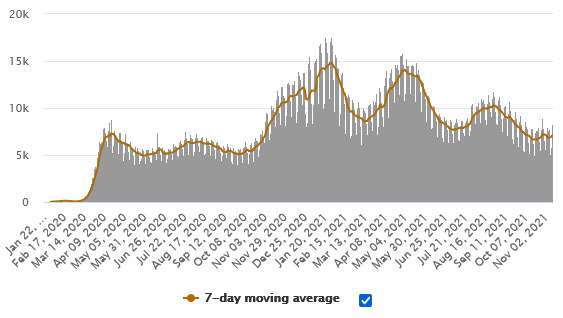

In any case, and despite the shortcomings of the available figures, a spike in cases and deaths from COVID-19 has been detected since the end of the summer, both for the world as a whole and for the most developed countries where the vaccination process has advanced most rapidly in 2021. This is no coincidence because, as we said in the introduction, the infection and death figures provided by many of the less developed countries grossly underestimate the incidence and lethality of the disease. As can be seen in Graphs 1 and 2, the world as a whole shows a more than worrying spike in cases and deaths which, as we shall see, affects even the most advanced economies, despite the fact that their governments have made free vaccines available to their citizens and the percentage of people who have received at least one dose reaches 70% of the adult population in almost all of them.

Figure 1. Daily cases January 2020 to 12 November 2021

Figure 2. Daily deaths January 2020 to 12 November 2021

Source: worldometer Coronavirus update

In the United States, for example, COVID-19, which during December 2020 and January 2021 was the leading cause of death, had, thanks to restrictions imposed by the authorities and progress in the vaccination process, fallen back to seventh place in July, and everything seemed to indicate that not only the United States, but all the more developed economies where the vaccination process, as can be seen in Figure 3, was progressing at a good pace, were close to controlling the ravages of the virus. But the situation changed dramatically in August, and COVID climbed to second place in the mortality rankings in September and was the leading cause of death among adults aged 35-54 years in the United States.

Figure 3. Percentage of the population fully vaccinated against COVID-19

Source: Our World in Data.

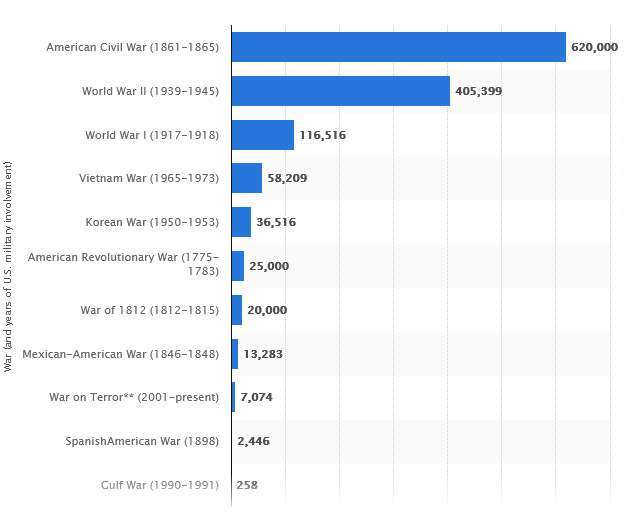

There is no doubt that the virus is still on the prowl and that while mortality peaks in recent months in the United States have not been as high as those recorded in December and January 2021, it is worth bearing in mind that the number of deaths on 15 September, 2,615, came very close to the 2,726 deaths caused by the terrorist attack on the Twin Towers on 9/11 in 2001, victims to whom Americans had paid a heartfelt and well-deserved tribute four days earlier. In total, COVID-19 caused the premature deaths of 56,537 Americans in thirty days in September 2021, comparable to the total number of casualties counted in the Vietnam War (58,209) over nine years, and leaving us with a staggering 1,885 casualties per day. No less impressive is the number of deaths counted since the beginning of the epidemic, which exceeds 781,000, a figure that, as I recalled in the inaugural lecture of the 2021-2022 academic year that I gave at the Abad Oliba CEU University on 29 September, comfortably exceeds the number of casualties in all the war conflicts fought by Americans since independence, with the exception of the deadly Secession War.

Figure 4. American casualties in war since 1775

Source: Statista

I mention these facts simply to emphasise that we are assuming with normality what is a genuine humanitarian catastrophe affecting countries such as the United States, which have sufficient resources and political-administrative institutions that are expected to have a high capacity to deal with emergencies and design effective public health policies to cushion the effects of the pandemic. Although somewhat better, the UK's figures of 138,193 cases and 2,085 deaths per million population are not far behind the former colony's 149,947 cases and 2,085 deaths per million population. As for the four largest EU economies, Germany, France, Italy and Spain, it must be said that, although they have somewhat better records than the United States and the United Kingdom, especially Germany, there is reason to believe that the authorities in some countries, either through incompetence or deliberately, have underestimated the magnitude of the tragedy in order to sweeten their management of it.

I will now focus on Spain, the country I have been following most closely for obvious reasons. The official figures for cases and deaths on 12 November are 5,047,156 and 87,673, respectively, with case and death rates per million inhabitants of 107,893 and 1,874, respectively, considerably lower than those of the United States and the United Kingdom. However, there are good reasons to believe that there was a significant underestimation of cases and deaths, specifically during the first wave that can be dated between 9 March and 10 May 2020. At that time, the Spanish health system did not have enough tests to diagnose the infection and the health authorities determined that only those patients who had tested positive could be certified as having died from COVID-19. As a result, thousands and thousands of patients became ill and many of them died in those nine fateful weeks without any record of being infected and dying from the virus.

Fortunately, we have alternative sources of information that reveal the gross underestimation of the official figures. Indeed, while the number of deaths due to COVID-19 is put at 26,478 deaths up to 9 May and 26,621 deaths up to 10 May, the estimates of the Daily Mortality Monitoring System (MoMo) of the Carlos III Health Institute estimate the excess mortality between 10 March and 9 May at 46,635, i.e. there are 20,157 (=46,635-26,478) more deaths than officially recognised by the government on 9 May. On the other hand, the statistics on weekly deaths implemented by the INE to estimate the effects of the virus, allow us to conclude that from the beginning of the 11th to the end of the 19th week of 2020, i.e. from 9 March to 10 May, there was an excess mortality of 49,863 people, a figure even higher than the excess mortality estimated in the MoMo reports.

There can therefore be no doubt that the government statistics grossly underestimate both the number of cases and the number of citizens who died prematurely from COVID-19 during March, April and early May 2020, when the virus broke out in Spain leaving a trail of pain and death. Missing from the figures for the first wave are at least two tens of thousands of deaths and a few hundred thousand unaccounted-for cases. It is an obvious corollary that the numbers of cases and deaths per million inhabitants are considerably higher than those reported in national and international statistics.

Despite President Sánchez's insistence on reminding us of his unwavering commitment to a fair recovery where none of the survivors are left behind, the truth is that the inaction, first, and subsequent improvisation, of his government in public health matters, turned the outbreak of the virus in our country into a major disaster, which placed our country at the head of the countries with the highest number of cases and deaths per million inhabitants, and our economy at the head of developed countries in terms of the intensity of the fall in GDP. Those who are irremediably left behind are the tens of thousands of Spaniards who lost their lives prematurely in the first wave, and the several million more who have suffered from the disease or suffered very severe economic losses that could have been largely avoided had the Sánchez government adopted the measures recommended by the World Health Organisation in January 2020.

Now the solution proposed by Sánchez and his separatist partners in the General State Budget to leave this nightmare behind us is to raise all taxes to finance more 'social' spending, when the majority of citizens who contribute to the Treasury are struggling to cope with the sharp rises in the prices of energy goods and the unstoppable increase in the cost of the consumption basket. Please, stop talking to us about the ecological and digital transition, or about the transformation of the production model, or about how wonderful the world will be in 2050, because for many of us there are only two certainties left at the moment: the first is that until a few years ago we could pay the electricity bill without worrying and even lead a comfortable life that allowed us to indulge ourselves from time to time; and the second is that your policies are holding back the creation of jobs in the private sector and feeding the 'need' to increase social benefits. Spain does not have a problem of a lack of training for the working-age population, since we export skilled labour, but of a shortage of jobs where these potential workers can generate income.