A missing vaccine: Low-income countries run out of stock

The term "vaccine nationalism" has been established to explain what is currently happening.

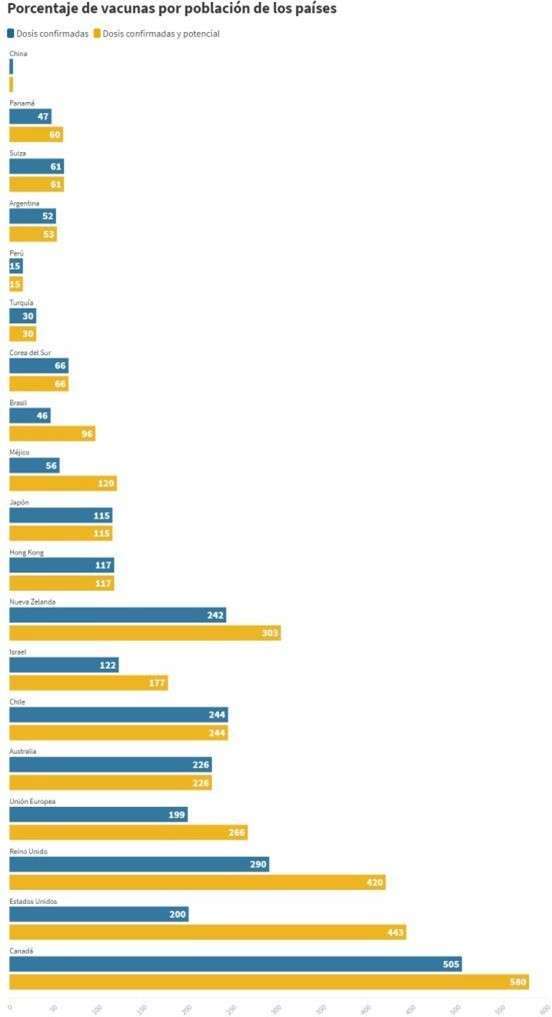

It has been denied over the past few months that we will manage to do better, and now that the vaccines have arrived, the fallacy is once again evident. When vaccines are already a reality, the willingness of wealthier states has been portrayed in a study by the Duke Center for Global Health Innovation, which shows that ten high-income countries have already purchased or have advance purchase agreements to vaccinate 100 percent of their population several times over. This is expected to result in low-income countries receiving the vaccines years later than richer nations.

Some experts have decided to use this term to define what is happening with the acquisition and reservation of serums. Richard N. Haass, president of the Council's study centre on international relations, explained to the BBC the meaning of this expression: "It can be described as a preventive nationalism"; and added: "It is very negative for governments to let themselves be carried away by this selfishness. If you have a large number of infected people in the world, given globalisation, the virus will continue to be active. There is a political, economic and strategic game behind vaccines that is a recipe for disaster, if no international agreement can be built".

A study led by Professor Joseph So, published in The BMJ, attributes vaccine nationalism to uncertainty about which vaccines will end up being effective. Countries that have been able to afford to buy spare doses from various pharmaceutical companies will secure their vaccine supplies in the future.

However, for César Hernández, Spain's representative on the European Union's vaccine advance purchase negotiation team, this term does not fit with the reality of purchase agreements: "Everything that has been done since the European vaccine strategy contemplates this aspect of solidarity, is in no way a look at what has been called 'vaccine nationalism'. Of course, it seeks to solve the problems of our citizens, but in the negotiations, there is talk of doses far beyond what would eventually be the first batch needs of European citizens. All contracts have clauses allowing donation or resale to third countries and humanitarian organisations. All of this is contemplated, in the negotiations, and in EU countries' policies. (...) It would not be fair to say that Europe is only trying to solve its problems, since there is also an expression of international solidarity".

A report by the Duke Center for Global Health Innovation estimates that if nations that have purchased more than their fair share of doses do not donate the surplus in time, many low-potential countries will have to wait until three years from now, which is how long it will take for pharmaceutical companies to produce enough vaccines to immunise the world's population.

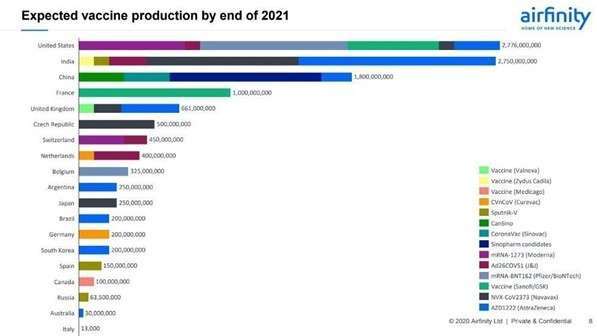

In addition to this forecast of a late arrival in developing countries, the analysis previously mentioned - published in The BMJ, which concludes that even if the 13 leading vaccine manufacturers were to reach their maximum production capacity, at least one fifth of the world's population would not have access to vaccines until 2022.

The People's Vaccine Alliance reports that 69 low-income countries will only be able to vaccinate one in ten people by 2021 unless governments and the pharmaceutical industry take action. According to the activists, the richest nations have bought 53% of the most promising vaccines, risking the supply of the rest of the low purchasing power.

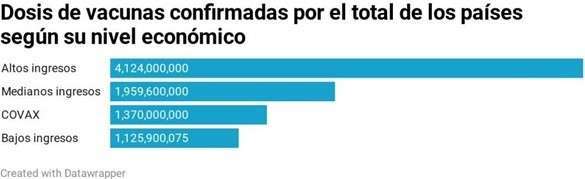

According to the Duke Center, high-income countries have so far signed advance purchase agreements for more than four billion doses, with another five billion doses under negotiation.

The strategy being followed by high-income countries is to secure vaccine stocks with manufacturers through financing serum production. This is the case of the United States, which, in return for supporting research, development and manufacture of five of the most advanced VID-19 vaccines, will receive priority access. Clearly, this is a move that low-income countries cannot emulate.

In the study published in The BMJ, experts add that without a globally coordinated approach to the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines, states could end up stockpiling their dose supplies. If high-income countries expand their purchases, less than 40% of every two vaccine doses (i.e. one vaccine course) would be left for low- and middle-income countries. In contrast, if nations share the doses they have purchased, the percentage would be greater than 40%. The study adds that, given the logistical and financing challenges in delivering these vaccines, stocks may not be so easily shared.

In fact, according to Duke's analysis, many countries could vaccinate several times 100 percent of their population. The most notable case is Canada, which will be able to immunise its entire population six times with the confirmed doses plus the reserved ones. It is followed by the USA, with doses to vaccinate all its inhabitants more than four times. In contrast, low- and middle-income countries will not be able to vaccinate 100% of their population with the amount of serums purchased so far.

For Spain, the Ministry of Health has estimated that 80 million people will be able to be vaccinated over the next year, which is more than 30 million more than the Spanish population. This amount is obtained from 10% of the total Pfizer/BioNTech vaccines that the EU has purchased. The Health Ministry has said that the remaining doses would become part of a strategic reserve, in case more vaccinations are finally needed during the next years, or to be sold or donated to other countries.

In a policy report published in Science Journal, several experts lay out a common ethical framework to build on when distributing vaccines, called the Fair Priority Model. In this publication, the authors argue that national bias in vaccine stockpiling is unreasonable when more doses are withheld than necessary to keep the transmission rate (Rt) below 1.

A large number of lower income countries rely on COVAX, an initiative led by the WHO and the international research alliance Gavi. Donors, both state and private, will donate funds to COVAX so that the organisation can negotiate a more affordable price with vaccine manufacturers. Once the doses have been procured, they will be distributed with UNICEF support to the 92 countries that have requested to participate in this initiative, to vaccinate a maximum of 20% of its population. As a precaution, 5% of the total doses will be stored to build up a reserve that may be useful in case of future vaccinations or to immunize refugees, for which no country is responsible.

It is estimated that for a two-dose vaccine, which corresponds to most serums, 2.28 billion doses will be needed to immunize 20% of the population in each country. COVAX has now confirmed the purchase of 1.37 billion, which is 910 million less than the requirement. If the potential doses of vaccines were confirmed, the figure would rise to 2.27 billion. Gavi director Seth Berkley has warned that "we urgently need to raise at least an additional $5 billion by the end of 2021 to ensure the equitable distribution of these vaccines to those who need them".

Among high-income and middle-income nations, the number of doses that have been confirmed for purchase is 6 billion, while developing economies have managed to purchase just over a billion in total.

Some of the developing countries have managed to secure a significant number of doses thanks to their domestic pharmaceutical industry. This is the case in India, which next year is predicting to obtain more vaccine doses than any other country through the Serum Institute, which has contracts to produce large quantities of AstraZeneca and Novamax prescriptions.

Those countries, such as India and South Africa, which have their own pharmaceutical backing, are in negotiations with the World Trade Organisation (WTO) to secure an exception to the enforcement of patents and other vaccine safety measures for the duration of the pandemic. The goal is to make manufacturing processes faster and cheaper, without fear of domestic manufacturers being sued or prosecuted. Organisations such as Médecins Sans Frontières defend this request. "It's a pretty logical response from the point of view of some countries that are seeing how countries with greater economic power or greater contacts are making advance purchases of a product that looks like they're not going to be able to access. The idea is to increase manufacturing capacity, rather than have more selected producers like the Serum Institute in India. Several laboratories could produce them at once," explains Alonso Ruiz, a researcher in innovation policies and access to medicines.

In this sense, last May an open letter was drafted, signed by more than 140 world experts and leaders (including the presidents of South Africa, Pakistan, Senegal and Ghana), addressed to all governments, stating the interest in vaccines "being free of patents, mass produced, equitably distributed and made available to all people, in all countries, free of charge". In addition, they call for a union of states to achieve a universal vaccine against COVID-19.

In addition to the main obstacle, the economic one, developing countries face other challenges in distributing or storing vaccines. The Duke study identifies several of these challenges that could be faced by countries such as India, Ethiopia or Peru. Some are the ability to maintain the cold chain (especially in rural and remote areas), the supply of needles and proper disposal of organic waste, or the lack of trained providers to distribute the vaccines.

Finally, they point to mistrust and misinformation among the population, specifically in unstable political climates. Experts fear something similar to what happened in the Democratic Republic of Congo during the outbreak of the Ebola epidemic in the eastern part of the country in 2018. Escorts were sometimes required

in regions with particularly active militias or where the population was opposed to the presence of the WHO. To try to prevent situations like these from occurring, plans are made to work with local community, religious and political leaders to achieve greater acceptance.

It is certain that if the world's population is not immunized, the risk of international contagion will remain. If there is one thing we have learned during this pandemic, it is that what happens on the other side of the globe ends up affecting us all, as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has argued in its annual Goalkeepers report.

To this end, the foundation collaborated with the Biological and Socio-Technical Systems Modeling Laboratory (MOBS LAB) at Northeastern University in Boston, which has already worked with seasonal flu simulations. On this occasion, the study developed two hypothetical scenarios on the percentage of lives that would be saved if the vaccine were distributed equally or not, assuming that the vaccine had been available since March 16.

In the first scenario, approximately 50 high-income countries would have received the first 2 billion doses, out of 3 billion, of a vaccine that is 80% effective. In the second scenario, all countries received 3 billion doses equally distributed. In the latter scenario, MOBS LAB estimates that 61% of deaths would have been prevented, compared to 33% in the first case. If the vaccine were 65% effective instead of 80%, 57% of deaths would have been avoided in the first scenario and 30% in the second. Researchers are trying to show what panic prevents nations from seeing, which is that if vaccines do not reach all countries equally, deaths will double and the pandemic will not be controlled.