The role of clandestine radio stations in Algeria's independence

The emergence of radio transformed media consumption habits in this country

To speak of radio is to speak, as Ryszard Kapuscinky would say, of "that desire for our voice to reach somewhere is a characteristic need of imprisoned people who cling like a plank of salvation to the world's faith in justice, who are convinced that to be heard is to be understood and, therefore, to demonstrate the justice of their cause and to win it.

Various studies on mass communication have shown that the media are a very effective instrument in the creation of public opinion; an opinion which - as a rule - tends to have very significant effects on society, even if there is no consensus on the nature and extent of these effects. This influence also depends on the more or less critical moments in society. As a rule, the media tend to be more influential in times of crisis. Underground radio stations are an example of this relationship between radio and history. What have all those people who have decided to set up an underground radio station been trying to do? To achieve power, revolution, independence or democracy? To show that the world wants to fight against censorship? To reach an audience they could not otherwise reach? Do these people really achieve their goals?

Radio was born in the 19th century and developed completely during the 20th century. For more than 100 years, it has always been there, reporting on a world that has always been thirsty for news, giving a voice to those who do not have one, awakening social sensibility and, on many occasions, questioning everything that is not true.

In the case of Algeria, radio has been evolving at the same pace as its society. It has witnessed some of its main historical events and has known how to adapt its forms and contents to the rhythm of the changes that this country has undergone in the second half of the 20th century. There is one type of broadcasting that sometimes goes unnoticed, and that is clandestine broadcasting, which is aimed at specific audiences and broadcasts in a specific territory, because of its political purpose. However, clandestine is not synonymous with minority.

Clandestine radio emerged during the first decades of the 20th century. There is no exact date because of the nature of this genre. However, its "boom" was from the 1970s onwards, although it had played a very important role previously in conflicts such as the Second World War or the Spanish Civil War. There is also no consensus on what an underground radio station is.

For example, Julián Hale speaks of them as "all those stations that are not the spokespersons of governments and that play some kind of subversive role, launching propaganda for tactical reasons against a particular area, as opposed to those that disseminate an ideology or an "objective truth" to the world in general. Quite a few authors talk about the underground as an element of propaganda or disinformation.

There are different criteria when talking about this type of radio. Óscar Nuñez Mayo defines clandestine radio broadcasting as "radio activity that is carried out exclusively for political reasons and lacks express official authorization, organized by individuals or groups who are marginalized by the political system prevailing in their country to which they direct subversive broadcasts, either from a station (legal or illegal) located within the country or from a station (legal or illegal) established abroad".

Although each person has a different perception of what a clandestine radio station is, they all agree on some basic concepts such as its political intent and the fact that it is run by persons or organizations that are persecuted in a given territory.

Any clandestine broadcast has a series of common features such as its temporality when born in specific circumstances and the struggle to change them; they are vehicles of propaganda since they spread their vision of the world; they are also considered channels of alternative information and instruments of struggle since they try to convince people that they must act to transform the reality in which they live. In this sense, they usually pay more attention to the content than to the form.

Luis Zaragoza says that to talk about clandestine radio during the Algerian war of independence is above all to talk about Franz Fanon. Fanon (1925-1961) was a revolutionary French psychiatrist, philosopher, and writer whose work is very influential in the fields of postcolonial studies, critical theory, and Marxism. He was part of the humanist currents of radical existence with regard to decolonization and the psychopathology of colonization. He was one of the creators of the clandestine radio station 'La Voix de l'Algérie Libre et Combattante'.

Throughout his short life (he died young of leukemia), Fanon supported the Algerian struggle for independence and was a member of the Algerian National Liberation Front where he was an organizer, leader and main broadcaster of some of the broadcasts of this front. This psychiatrist was born on the island of Martinique, at a time when it was a French colony. In 1940, the naval troops of Vichy France settled on this island where Fanon still resided. These troops - according to some written documents - allegedly acted in a racist manner. This continuous contempt for his person greatly influenced the later ideology of this philosopher.

At the age of 18, Fanon left his hometown for Dominica, where he joined the French Liberation Forces, and later joined that country's army in the war against Nazi Germany, notably in the Battle of Alsace. In 1945, Fanon returned to Martinique for a short period and six years later he graduated as a psychiatrist and began to practice under the supervision of the Catalan doctor F. de Tosquelles, from whom he took the idea of the importance of the cultural in psychopathology; an idea that he later applied to the concept of radiofusion.

In 1953 he moved to Algeria where he took up the post of Head of Service at the Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Hospital. There he began to apply his own techniques; techniques that highlighted the cultural for both normal psychology and pathology. Fanon arrived in Algeria just as what was to be the definitive insurrection against French rule was about to break out. His brief contribution is very important in this study since he was the first theoretician to highlight the potential of clandestine radio stations to transform a people's relationship with reality and with radio itself.

His ideas spoke of the absorption of dominant cultures or ideologies by the subjugated; absorption which, in his opinion, produces pathological results, both at the social and individual level. He also dedicated part of his life to an analysis of the replacement of discriminatory forms of social relations that are the product of the expression of new cultural and political forms that appear among the subjugated. These political-cultural forms are the expression of the existential essence of groups marginalized by the dominant culture and inevitably produce a new humanity. And finally he applied in his analysis, the cathartic power of revolutionary violence. In his books, especially in the latter, the idea prevails that only violence can totally liberate from the legacy of subjugation, eliminating feelings of inferiority and producing a consciousness of control over one's own destiny.

After the start of the Algerian War of Liberation in November 1954, Fanon joined the National Liberation Front (FLN) clandestinely and became one of its main strategists. Two years later, in 1956, he wrote his Public Letter of Resignation to the Resident Minister and was consequently expelled from Algeria in January 1957.

Algeria's war of independence was one of the cruelest and bloodiest wars of decolonization in the 20th century. A devastated France after the Second World War had to face this conflict that caused the fall of several governments of the Fourth Republic, before it ended, and almost led the country to civil war. The Algerian nationalist movement preceded the others in its starting point and would end after the remaining Anglo-French colonial territories in the area had achieved independence.

This situation caused General de Gaulle to return to power. De Gaulle had retired from politics in 1953 after unsuccessfully trying to impose his ideas of a reforming republic with a stronger executive; measures that he wanted to implement in the immediate post-war period.

A French colony since 1830, Algeria had a significant European minority at the time of the war of independence. 1954 is considered the date of the beginning of this conflict. However, there are certain facts such as the rebellion at the Zaatcha and Zibane Oasis, led by Sheikh Bouziane between 1845 -1850, and after being beheaded with his son, their heads, preserved in formaldehyde, were still on display at the Musée de l'Homme in Paris until 1967; or the Tuareg revolts at the Hoggarliderade led by Sheikh Amoud Ben Mokhtar between 1877- 1912 which caused some instability: instability which ended with the country's independence.

During the Second World War, the Algerians supported their metropolis, hoping for a fairer deal at the end of the war. Once this war was over, however, it became clear that the attitude of the French authorities was not exactly open: the French forces caused several thousand deaths by breaking up the peaceful rallies of May 1945.

In this environment of social instability, the National Liberation Front emerged in 1954 and took over the political direction. In the early morning of November 1, this resistance movement launches an attack on military and police installations, warehouses and communication centers. Furthermore, the FLN issues a proclamation from Cairo, calling on the Muslims of Algeria to join this struggle for the independence of their country.

The armed groups of the Revolutionary Committee for Unity and Action (CRUA) decide to act. The FLN (National Liberation Front) spread to the cities and mountains. In 1955 the guerrillas killed 123 settlers and France responded by killing 12,000 Algerians and declaring a state of emergency.

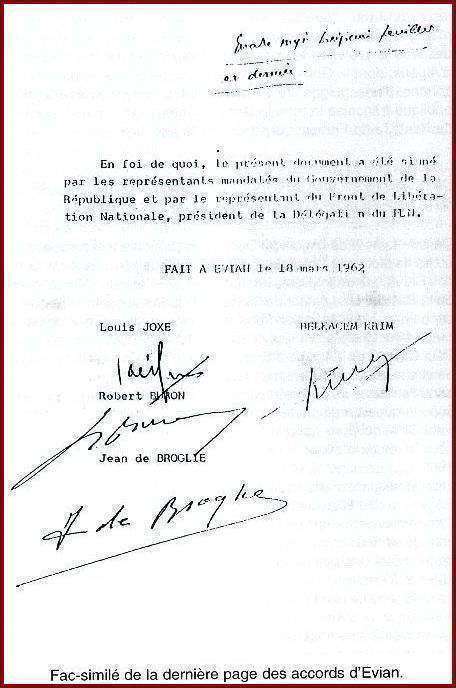

France refuses to prepare a plan to decolonize Algeria. The consequence was an out-of-liberation in which one million people died and which ended in 1962 when France recognized the right to self-determination in the Evian agreements, that is, in the General Declaration of the Two Delegations of 18 March 1962"..

The referendum held in France on June 17, 1962, was approved by more than 90% of the voters and the consultation by direct and universal suffrage was held in Algeria on July 1, 1962, achieving almost unanimous support for independence. General de Gaulle announced Algeria's independence on 3 July, although it would not be proclaimed by the Provisional Government until 5 July 1962, the 132nd anniversary of France's entry into Algeria.

Fanon applied in his theories the classic scheme of class struggle between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie--a struggle which he saw as a conflict between a dominant society and a dominated society. In the radio field, this division would be marked by Radio Algiers, a radio station based in Paris, and, on the other hand, by the clandestine broadcasts of the National Liberation Front, whose main message was that of revolution.

Luis Zaragoza points out that "until 1954 the Algerian natives had been totally disinterested in radio". The Algerians, whose priorities at that time were different, completely rejected the use of a radio. The creation of the FLN and the start of clandestine broadcasts of La Voix de l'Algérie Libre et Combattante transformed this situation, according to Bassets. The technology which until then had been a symbol of colonial oppression was turned in this conflict into an instrument of liberation. Listening to the FLN's radio was in itself an act of protest and commitment to the cause.

These broadcasts transformed, in a way, some of the habits of Algerian society's hierarchy. However, this transformation was not only the result of the emergence of the FLN and its clandestine broadcasts, but had other causes.

For France, Algeria was just another province in the structure of the French empire. Unlike other countries of the Maghreb, the Algerian administration depended on the Ministry of the Interior and not on the Ministry of the Colonies. The media structure also reflects this fact in that Radio Algiers was integrated into the French Radio and Television (RTF) and not into the company set up to manage the stations in the colonies. In short, Algeria was a symbol of French nationalism, which it had difficulty in ridding itself of.

This close link did not correspond to the social situation. Algeria was a territory where instability was present. This instability led to the emergence of nationalist sentiments which in a way came through the Arabic broadcasts from Italy and Germany during the 1930s; broadcasts which exposed Algerians to the Arab cultures of the Middle East.

On 1 November 1954, the Voice of the Arabs from Cairo announced the start of the war of independence:

This first communiqué did not directly mention the existence of the FLN, a political-military entity that several hours earlier had made itself known in Algeria with a succession of attacks that left seven dead and several wounded. It was the beginning of one of the cruellest decolonization conflicts of the 20th century.

From the beginning, Egyptian broadcasts played a key role in the development of this war and in the international publicity of the LN. In fact, Egypt was the first country to publicize on radio what was happening in Algeria. Only one year after the beginning of this conflict, information about the revolution was already being broadcast every afternoon in a fifteen-minute space addressed to the French in French. The voice of the LN is addressed to you from Cairo" was also broadcast. This was a political radio commentary in Arabic. In 1958, the FLN created the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic and this radio station changed its name to the Voice of the Algerian Republic.

During this period, as many as sixteen countries supported this cause in the region under a variety of names, but with one element in common. The words Swat al-Djazaïr (Voice of Algeria) appeared in all the broadcasts. According to data collected by Luis Zaragoza "from Tunisia, a one-hour programme was broadcast three times a week from 1956 onwards. From Damascus, a daily program that stopped broadcasting in 1961, when Syria separated from Egypt. From Tripoli there were three weekly broadcasts and three different ones from Benghazi. When Iraq had its own revolution in 1958, Baghdad gave up broadcasting time to the FLN.

In October 1956, the FLN stepped forward and decided to take over its own radio station. On 16 December of that same year, in the midst of escalating tension, La Voix de l'Algérie Libre et Combattante was born. "Here is the radio station of free and fighting Algeria, the voice of the Liberation Front addresses you from the heart of Algeria"; this was its first message.

A message that was heard every day for the next few years by listeners of this radio, which broadcast on short wave for two hours a day (one hour in Arabic, half an hour in Kabylia and half an hour in French). Their information was in a way propaganda for the National Liberation Front. They talked about what was happening at the time, but with a marked ideological bias that appeared, for example, in the dissemination of patriotic songs or religious sermons.

The appearance of this radio transformed the habits of media consumption in this country, something that Fanon had already said before his death. "In less than twenty days the existence of radio receivers is exhausted. In the souks there is a trade in used radio receivers. The Algerians, who were apprenticed to European radio specialists, opened their own workshops [...]. The lack of electricity in vast regions of Algeria poses a number of problems for the consumer. Since 1956, battery-powered radios have been the most popular and thousands of devices have been sold to Algerians in a few weeks.

Algerians probably used these devices to make a judgment on what was happening in their country because the press was very manipulated. The appearance of this radio was a major problem for France, which tried to put an end to it on several occasions. The French air force bombed the area twice in 1957 without managing to stop the FLN from broadcasting. In fact, the opposite happened, as the FLN increased its presence by opening studios and fixed transmitters in 1959, which allowed them to broadcast from Nador in Morocco. These somewhat epic Fanon superstitions were not far removed from reality. It is true that the Muslim population gradually increased between 1955 and 1961.

France was concerned about this new player, who had not been on its board from the start, and decided to put an end to this type of broadcasting. Different measures were taken, but without a doubt one of the most striking is the one that forced traders to keep a record of who bought radios and the one that restricted the sale of batteries, as explained by Zaragoza in his book "Voces clandestinas".

In May 1956, a law forced journalists to speak of "bandits" when referring to the FLN instead of "nationalists". Faced with this situation, Radio Algiers began to broadcast its programmes in Arabic and Kabylia to reach a population which had been marginalized from the air for decades. In addition, it began a campaign of interference with Voice of Algeria broadcasts. The strategy of FLN radio listeners was to reinterpret the information they were able to get through these interferences.

Lastly, the French Government resorted to black propaganda. In other words, they began broadcasting under the name of the FLN radio to discredit the movement and confuse the listeners. In short, from the outset, France saw this radio station as a threat.

During these years the radio reached a large audience, but it was with the appearance of transistors that it became widespread. The transistors invented in 1947 made it possible to design much smaller, lighter and, above all, economically accessible devices; something that helped virtually anyone to enjoy what today is a right: freedom of information.

With the arrival of the transistor, FLN continued to broadcast with the condition in its favor that there was no longer geographic isolation; facts that favored the emergence of a collective identity in communities. Since then, radio became an ally of the revolutionary movements and an element of modernization.

As time went on, the conflict became bloodier. In addition to the violent actions of the FLN, there was also repression by the army. Algiers became a centre for coups. The military who did not accept Algeria's independence triumphed in May 1958 by creating a Committee of National Salvation and demanding the return to power of General de Gaulle in order to avoid a civil war in France.

De Gaulle began to negotiate with the FLN and proposed to the Algerian people that a referendum be held on their future, something which was not entirely appreciated by some sectors of the French bourgeoisie in Algeria. On January 8, 1961, seven out of ten votes in the metropolis and in Algeria were in favor of self-determination.

However, it was not until 1962 that the United Nations recognized Algeria as an independent country. This period of time was the bloodiest; a violence partly created by the emergence of a new actor. It was a far-right paramilitary group called the Organisation Armée Secréte (OAS), made up of some members of the "piedsnoir" army and Europeans living in Algeria.

Since its emergence in the early 1960s, this group has also begun to broadcast clandestinely, calling on its listeners to fight for a French Algeria and criticising what it considers to be traitors. Their broadcasts began with the hymn "Chant des Africains" and they proclaimed themselves "Radio France, la Voix de l'Algérie Francaise".

These broadcasts coincided in time with the broadcasts made by Radio Algiers, which they tried to boycott on certain occasions. On 22 April a group of intransigent soldiers took over the studios of the official radio station, demanding the resignation of De Gaulle and asking the soldiers to disobey the government. This action failed in part because of the absence of transistors. On the evening of 23 April, de Gaulle spoke on radio and television in a speech that was repeated every fifteen minutes.

The OAS broadcasts continued, but did not achieve their objectives as the negotiations between the French government and the GPRA advanced until the Evian agreements were signed, which included a ceasefire from 19 March 1962. A new referendum ratified this in both Algeria and Morocco. A new stage was beginning for this country. Since then, Algeria has been an example of many national left-wing movements and has maintained an active policy of support for decolonisation. A policy that has also left its mark on the radio.

The conflict for the independence of Algeria was one of the first in history in which the radio was a weapon of war, another actor on the game board since it became an instrument of propaganda (both by the settlers and by the FLN). In short, the broadcasts of the "Voix de l'Algérie Libre et Combattante" were a great weapon from the psychological outside.

Radio had certain advantages over the written press. The main one was that it could reach more people by creating, in a way, public opinion, since people in wartime demand more information, since the fact itself arouses their interest and, above all, their concern.

With all this, a development is produced, a growth that should be valued in its fair measure since many of these emissions are propagandistic. However, it is true that these types of broadcasts are capable of generating that feedback of opinion since they probably said what the Algerian population at that time wanted to hear; they were a breath of fresh air that in one way or another managed not to lose hope.

In the case of Algeria, setting up a radio was not very complicated as it coincided with the invention of the transistor. And since radio can reach all sectors of society beyond their socio-economic class or education, it became the preferred medium for both the FLN and the settlers with Radio Algiers, to express their views and encourage revolution, rebellion or liberation; a fact, which they undoubtedly achieved. However, it is necessary to reiterate that the fact that Algeria achieved independence was not the only consequence of the emergence of clandestine broadcasting, although it did play a very important role which has gone largely unnoticed in the studies of this conflict.

What happened in Algeria has served as an example for other current conflicts. With the Iraqi army's offensive to recover the city of Mosul from the hands of the self-determined Islamic state in the autumn of 2016, several people discovered that there was a clandestine radio station broadcasting under the name of Alghad ("tomorrow" in Arabic). Daesh's performance was similar to that of France. After discovering the existence of this radio, they started a war on the airwaves by banning the sale of radio sets and moving their own station to Mosul to broadcast on the same frequency as Alghad.

Clandestine radio stations are both a threat and a release; they will not cease to exist as long as there is an informational and political context that demands them. The fact is that a man who has something to say and cannot find listeners is in a bad situation. But even worse are the listeners who cannot find anyone who has something to say to them.

In times of war it is difficult to find information and in the case of Algeria, the "Voix de l'Algérie Libre et Combattante" was able to try to change this fact; it managed to transform, in its own way, the radio consumption habits of Algerian Muslims and, above all, it showed them that being informed is not a crime and that anyone has the power to choose which medium they want to follow according to their ideological line.

BASSETS, Lluís. De las ondas rojas a las radios libres, Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 1981

BASSETS, Lluís. De las ondas rojas a las radios libres, Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 1981

HALE, Julián. La radio como arma política. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 1979.

KAPUSCINSKI, Ryszard. El imperio. Madrid: Anagrama, 2007

NÚÑEZ MAYO, Óscar. La radio sin fronteras: radiodifusión exterior y comunicación de masas. Pamplona: Universidad de Navarra, 1980

WOLF, Mauro. Los efectos sociales de los media. Barcelona: Paidós, 2001.

ZARAGOZA FERNÁNDEZ, Luis. “¿Tiene futuro la radio clandestina?”. Comunicación y Hombre, 2017, nº 13, pp 151-166

ZARAGOZA FERNÁNDEZ, Luis. Voces en las sombras. Una historia de las radios clandestinas. Madrid: Cátedra, 2016